Table of Contents

Share This

Section 4: Timeline

Inspired by the CHamoru/Chamorro concepts of mo’na, pa’go, and tatte, this timeline presents history in both a chronological and relational manner. The table covers important historical moments in Guåhan’s history showcasing the role that the CHamoru people, since the onset of American rule, have played in seeking a pathway towards self-determination and decolonization. The sails highlight the relationship of events in Guåhan to those taking place regionally, nationally, and internationally during a given moment in time.

Mo’na, Pa’go yan Tatte

How can a circular understanding of time and history help us imagine the possibilities for Guåhan’s future and quest for self-determination?

Similar to other Native Pacific Islander cultures, CHamoru culture perceives time as circular rather than linear. This circularity allows for the simultaneous existence of the past and the present and a connection to the future. As CHamoru scholar Dr. Michael Bevacqua explains, “A linear interpretation of time means that as we move through history, things happen one after the other, in a forward progression…things change and never return to a previous point.” This contrasts to the CHamoru understanding of time where the past is always with us.

CHamoru historian Dr. James Viernes describes CHamoru-Micronesian understandings of time “as fluid cycles in which the past, present, and future are interdependent on each other, entangled in infinite trajectories that are forever a part of our Islander worldviews.” Indeed, as part of Guåhan’s efforts toward self-determination Guåhan’s people are not merely observers but, as Viernes says, active agents past, present, and future that “make history happen.”

Sacred Vessels

In the CHamoru culture, the canoe is a means of transportation. Historically, it enabled people to explore the horizons and brought CHamorus back home. Canoes are also sacred, spiritual vessels, lifelines during times of famine and environmental stress, and conduits connecting humans to ancestors and spirits of the natural world. Sailing, like many things in life, requires planning as well as knowledge of your equipment, where you want to go, and how to get there. There are times the wind propels you forward, and times it holds you back.

More recently, the CHamoru outrigger canoe has been used as a symbol of the resilience, innovation, and strength of the CHamoru people, similar to the latte and slingstone. Pohnpeian-Filipino scholar and Guåhan historian Dr. Vicente Diaz describes the canoe as a metaphor that carries meanings of CHamoru culture and history as well as what it means to be Indigenous in this place. The canoe, impacted by colonialism as seen in its diminished use and displacement from CHamoru culture, has reemerged in the articulation of the politics of decolonization and self-determination for Guåhan. It represents cross-cultural connections with other Micronesians and Pacific Islanders and is the vessel from which the continuing stories of Guåhan’s efforts toward self-determination are carried and new possibilities are imagined and pursued.

The American colonization of Guåhan has presented great navigational challenges for the journey of the CHamoru people. The new administration brought another language to learn and a different way of thinking, living, and doing things. Yet, the CHamoru people understood early on that when the US Navy took over, they were not being treated fairly and they accordingly made their grievances known to the American government. Like seafarers, they sought to understand the tools at their disposal and used lessons from the past to guide them. Through World War II and Japanese occupation, postwar reconstruction, and urbanization the CHamoru people have utilized the tools of democracy (submitting petitions and lobbying in Washington, DC), joined the US military, secured increased media coverage, and elected powerful leadership, to make their voices heard.

While the seas have been rough and the weather uncooperative, the CHamoru people’s navigation of this journey on their physical and metaphorical canoes remain steadfast and reliable, even through these uncertain times.

Timeline table with sacred vessels

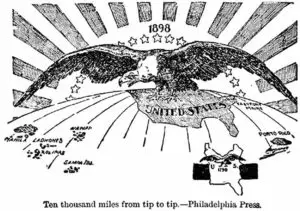

US gains possession of Puerto Rico, Guåhan, and the Philippines at the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Guam’s first petition to US Congress, written 17 December 1901, highlighted the excessive power of the naval governor and the lack of power among CHamorus, calling for a permanent government in Guåhan, rather than a military government. Subsequent petitions were submitted in 1917, 1925, 1929, 1933, 1936, 1947, 1949, and 1950. The first petition in 1901 contained 32 signatures; a petition in 1933 had collected nearly 2,000. Some of the petitions were claimed to have been “lost” in the files, were never answered, or were rejected due to heavy opposition from the US Navy.

- De Lima v. Bidwell

- Goetze v. United States

- Dooley v. United States

- Armstrong v. United States

- Downes v. Bidwell

- Huus v. New York and Porto Rico Steamship Co.

In 1917 Naval Governor Captain Roy Smith established the First Guam Congress. Leaders in the Guam Congress made it clear that the “most important issue to them was the question of Guam’s political rights and a more democratic form of government under the United States.” However, their views were often ignored by the US Navy.

On 4 December 1930, US Naval Governor Willis W. Bradley created a Bill of Rights for the CHamoru people modeled after the Bill of Rights in the US Constitution. It included the right of writ of habeas corpus and the ability to vote in local elections regardless of race or sex. It never went into effect. However, when Guam’s legal codes were revised in 1933 many of the provisions were later incorporated. These rights, though, could be wiped out by whomever was governor of Guam at the time.

In 1931, Governor Willis Bradley dissolved the First Guam Congress and held the island’s first general election on March 7th. Those elected became members of the Second Guam Congress, which consisted of a House of Assembly, with 27 members elected for two-year terms, and the House of Council, with 15 members elected for four-year terms. Governor Bradley opened the first session on 4 April 1931.

In 1936, the 2nd Guam Congress sent Francisco B. Leon Guerrero and Baltazar J. Bordallo to lobby in Washington, DC for US citizenship for the CHamoru people. The two were well received by empathetic individuals in the media and the US Congress familiar with Guahan’s plight. Strong opposition came from the Department of State and the Secretary of the Navy, citing rising tensions with Japan. The pair also visited President Franklin Roosevelt. Congress revisited the issue in 1939 but the start of World War II ended any further consideration.

Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) Trusteeship established under the United Nations in 1947.

In 1948, after WWII, Naval Governor Charles A. Pownall and the Secretary of the Navy gave Guam Congress powers to create laws for Guåhan, upon the governor’s approval, and the power to approve laws proposed by the naval governor. The Secretary of the Navy, however, had the power to override vetoes. The move was well received, and dubbed the Interim Organic Act. The excitement about these benefits were short-lived. The governor could unilaterally pass laws and veto legislation when the Guam Congress was not in session. Military condemnations of land and unfair wage discrimination against local workers only made things worse and pushed the CHamorus and their allies in the mainland into action.

In 1949, a Guam House of Assembly committee, investigating violations of a prohibition against Americans owning local businesses through Guamanian “front men,” subpoenaed a US citizen, Abe Goldstein, who had financed a women’s clothing store. Goldstein, a civilian, refused to testify. The committee issued a warrant for Goldstein’s arrest, but Pownall intervened. Angered, the assembly passed the Organic Act bill and voted unanimously to adjourn until the US Congress acted on it. CHamoru leaders worked with the US media to amplify their message across the country. Pownall dismissed congressional members who refused to attend a special joint session that he convened threatening to hold new elections to replace them. President Harry S. Truman then forced the US Navy to transfer the administration of Guåhan to the Department of the Interior within 12 months.

In May of 1949, Guam Congress sent FB Leon Guerrero and Antonio B. Won Pat to Washington, DC to lobby for the passage of an Organic Act. Other CHamoru leaders lobbied in Washington, DC including Agueda Johnston, Concepcion Barrett, and BJ Bordallo. On 1 August 1950, President Truman signed the Organic Act of Guam into law. The Act established a non-military, civil government in Guam; granted congressional US citizenship to island residents and their descendants; and designated the island’s political status as an unincorporated territory of the United States. The Organic Act was celebrated as a victory. But questions soon arose as to whether civil government meant self-government. Even more questions arose as to whether the US citizenship granted in the Organic Act truly afforded the protections that many believed it would.

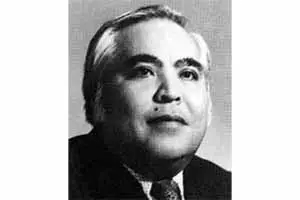

In 1960, businessman Joseph Flores was the first CHamoru to be appointed Governor of Guåhan. He followed civilian governors Carlton Skinner, Ford Elvidge, and Richard Lowe. Flores served for one year and is known for establishing a vocational-technical education program. As governor he advocated self-rule for Guam and an open-door policy. He established public health centers in Mangilao, Piti, Talofofo, and Asan. He also ensured that the Department of Public Works paved the Agat-Umatac Road for the first time.

On 21 August 1962, President John F. Kennedy signed an Executive Order which rescinded the navy’s wartime authority to refuse entry to civilian visitors for security reasons. This unleashed the island’s tourism potential and ushered in an era of unprecedented economic and social advancement. Governor Manuel FL Guerrero, the second appointed governor of Guåhan, established the Guam Tourism Commission and worked to increase plane routes to bring tourists to Guåhan. He also worked to modernize Guåhan’s economy. He changed the face of the island through urban renewal programs that addressed housing shortages, building modern residential subdivisions in Sinajana, Tamuning, Piti, Dededo, and other areas.

On 11 November 1962, Typhoon Karen hit the island of Guåhan. The New York Times reported that the island was “struck by 200-mile [per hour] winds” and “seven persons died, thousands were made homeless, [and] businesses were wrecked…” The federal aid provided in the aftermath of the typhoon helped in the rebuilding of the island and the increased use of concrete for homes and other structures.

Congress of Micronesia (of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands) from 1964-1979.

Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 (Hart-Cellar Act).

In 1960, the United Nations passed a Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, proclaiming the necessity of bringing an end to colonialism. The Declaration compelled colonizing nations to figure out what to do with their territories. For the United States, this included Guåhan and the Trust Territory of Pacific Islands (TTPI) in Micronesia.

Nine years later the First Guam Constitutional Convention was held to review and propose revisions to the Organic Act. From 1 June 1969 to 19 June 1970, 43 elected delegates participated in the convention and recommended 34 changes to the Organic Act of 1950. No action, however, was taken on the recommendations.

In 1970, Guåhan elected its first governor, Carlos G. Camacho, a local politician and dentist. He also served as the last presidential appointee in 1969. His term was marked by a great economic boom and major hotel construction projects. Camacho made a concerted effort to bring CHamorus who studied in the US back to work for the local government. Using government resources, he increased economic opportunities by granting incentives and offering various forms of assistance to businesses in the private sector.

In 1970, Governor Carlos Camacho established a Governor’s Advisory Council on Political Status to discuss the possibility of the reunification of the Mariana Islands. In fact, initial discussions about Marianas reunification had begun in the early 1960s, and since 1965, leaders from both Saipan and Guåhan had traveled back and forth frequently to engage in talks. The issue was brought before the people of the Marianas and separate plebiscites were held in the Northern Marianas and Guåhan in November 1969. While NMI voters approved reunification, Guåhan voters rejected it, and instead, each entity continued to pursue their individual negotiations with the US government.

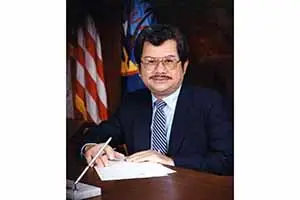

On 10 April 1972, US Congress passed a law establishing the offices of Delegate of the Territories of Guam and the Virgin Islands. This finally gave Guåhan and the Virgin Islands representation in Congress with two-year terms. Elected officials could speak on the House floor and introduce legislation though they could not vote on the floor. On 3 January 1973, Antonio B. Won Pat became the first resident of Guåhan to take the oath of office as a member of the 93rd Congress. The emergence of delegates to Congress from US territories is derived from an ordinance passed under the Congress of the Confederation—a time that predates the US Constitution.

In 1973, the Guam Political Status Commission was created to determine what political status was desired by the people of Guåhan. It was the first official body set up to address Guåhan’s political status. The Commission provided the public information about the legal and political status of Guåhan with the US. Chaired by Senator Frank G. Lujan it was comprised of nine senators: Joseph F. Ada, Antonio M. Palomo, Adrian C. Sanchez, Francisco R. Santos, Richard F. Taitano, Paul M. Calvo, Jesus U. Torres, and Paul J. Bordallo. The commission suggested that Guåhan’s interim status be similar to the commonwealth status of Puerto Rico and the one being negotiated by the Northern Marianas at the time. However, the commission faced difficulty in moving the issue of political status with inaction by US Congress and the local community. The commission recommended the development of a constitution to extend greater control over Guåhan’s governance.

The 13th Guam Legislature created the second Political Status Commission in 1975. The commission was tasked with educating the public about the political status options and open negotiations with the federal government. The new law identified the specific problems the commission was to try and resolve such as shipping, immigration, greater regional participation and other restrictions to Guåhan’s economy as a result of federal controls. This Political Status Commission was composed of 15 members from both political parties and two village commissioners (mayors). Republican Senator Frank Blas was the Chair and members were Edward Duenas, Thomas VC Tanaka, Jr., former Lt. Governor Kurt Moylan, Dr. Pedro Sanchez, and Democrats Carl TC Gutierrez, Adrian Sanchez, Francisco R. Santos, Edward Charfauros, Delfina Aguigui, James McDonald, Eugene Ramsey and Joseph Rios. Later a law expanded the membership to include appointees from the Commissioners’ Council Gregorio A. Calvo and Roman Quinata.

In 1976, US Congress passed a law authorizing Guåhan and the US Virgin Islands to create their own Constitutions. The following year, Guam lawmakers passed a law establishing a Second Constitutional Convention to draft a Constitution for Guåhan. The draft was approved by President Jimmy Carter. Although initially formed to address issues of preserving CHamoru language, the grassroots group Peoples Alliance for Responsive Alternatives (PARA) opposed the ratification of the Guam Constitution on the basis that it was not a true act of self-determination. When put to a vote, most voters rejected the newly drafted Guam Constitution.

By May 1980, Governor Paul M. Calvo created the first Commission on Self-Determination. Similar to the Political Status Commissions of the 1970s, it was tasked with gauging the desire of the people of Guåhan as to their future relationship with the United States. The Commission then organized a task force for each political status option and conducted a public education campaign on the advantages and disadvantages of each status.

After the campaign was completed, the commission conducted a plebiscite to establish the people’s choice on 30 January 1982. There were seven available options for consideration, including: Statehood; Independence; Free Association; Territorial Status with the United States; Commonwealth Status with the United States; Status Quo; and Other.

With the formation of the Commission, significant questions of debate arose: Who is CHamoru and how are they identified? Who is the “self” in “self-determination?” Does the right to self-determination only apply to the CHamoru people? Should non-CHamoru residents be considered in this process?

The debate became heated. Some advocated that CHamorus should be the primary participants in any effort at self-determination. Other vocal non-CHamoru US citizens opposed the idea and felt the vote should include everyone. After much discussion the Commission agreed to define a CHamoru as “all those born on Guam before 1 August 1950 [the date of the Organic Act’s passage] and their descendants.”

In 1982, the first Guåhan plebiscite was held, allowing all registered voters to participate. Commonwealth Status was selected by 49 percent of voters as the preferred political status option. Organization of People for Indigenous Rights (OPI-R) members, including future Congressional Representative Robert Underwood, testified before the United Nations Committee on Decolonization regarding Guåhan’s continuing status as a non-self-governing territory.

In January 1984, the Guam Legislature passed a law establishing the second Commission on Self-Determination. This Commission was to produce a document to be submitted to Washington, DC. A vote on the Commonwealth Act draft would be held before it was submitted to Congress. The Commission produced a draft and submitted it to Congress in 1985. Only 39 percent of Guåhan voters participated and the Commission decided to rewrite some of the articles that had been rejected, A special election was held in November with a 57 percent voter turnout. The document was approved in its entirety and the Commission submitted the draft Commonwealth Act to Congress in February 1988.

Compact of Free Association signed with the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of Palau in 1986.

The speedy negotiations and innovative agreement between the Northern Marianas and the US shocked many Guåhan residents.

The voters of Guåhan had rejected reunification with the Northern Marianas in 1969, fearing the financial burden of developing the neighbor islands and because the Northern Marianas CHamorus, who had been under Japan’s pre-World War II rule, had assisted the Japanese military in their wartime occupation of the island. The Northern Marianas had been territories of Japan after World War I. The CHamorus of Guåhan had remained loyal to “Uncle Sam” during those agonizing years of World War II, many suffering starvation, torture, forced labor and death at the hands of the Japanese. Most also lost their homes and businesses in the American bombardment and recapture of the island.

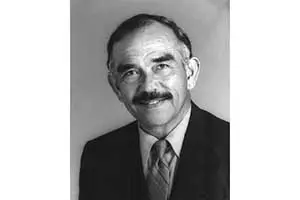

The loyalty of Guåhan’s CHamoru community, however, was not rewarded. In fact, over the next few years the Commonwealth Act was submitted continually to the US Congress during the tenures of Congressman Vicente “Ben” Blaz (1985-1992) and Congressman Robert Underwood (1993-2002) but languished during the administrations of President George HW Bush and President Bill Clinton. The Commonwealth Act remained at a standstill in 1997. The major objections, again, had to do with CHamoru self-determination, immigration, and labor control.

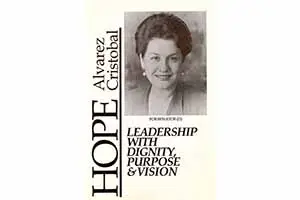

The CHamoru Registry was created by Senator Hope A. Cristobal in December 1996, to record “the progress and identity of the CHamoru people.” The law says the registry would be used for historical, ethnological and genealogical purposes, as well as for the future exercise of self-determination by the indigenous people of Guam.

The CHamoru Registry defined CHamoru people as all those born on or residing on Guam on 11 April 1899, including those temporarily absent from the island on that date and who were Spanish subjects [under Spanish control] who after that date continued to reside in Guam or other territory over which the United States exercises sovereignty and have taken no affirmative steps to preserve or acquire foreign nationality.

The Commission on Decolonization was established by the 24th Guam Legislature in 1997 to enhance the efforts of the Commission on Self-Determination. Its purpose is to educate the people of Guåhan of the various political status options available. The Commission on Decolonization, however, was inactive for several years during the 2000s. Governor Edward B. Calvo relaunched the Commission on Decolonization in 2011 and appointed Edward Alvarez as Director. The Commission on Decolonization is comprised of 10 members of the community and the Governor of Guam, who serves as Chair. The current Executive Director is Melvin Won-Pat Borja, appointed by Governor Lou Leon Guerrero.

Often confused with the CHamoru Registry, the Guam Decolonization Registry (GDR) plays a powerful role in actualizing Guåhan’s political destiny. According to Guam Law, until 70 percent of native inhabitants are registered on the GDR, a political status election cannot occur. It has not yet garnered enough registrants to move forward.

The law defines native inhabitants as people who became US citizens by virtue of the authority and enactment of the 1950 Organic Act of Guam and their descendants. A descendant is defined as, “a person who has proceeded by birth, such as a child or grandchild, to the remotest degree from any native inhabitant of Guam, and who is considered placed in a line of succession from such ancestor where such succession is by virtue of blood relations.”

In 2000, Guåhan’s government passed a Plebiscite Law which provided for a “political status plebiscite” to determine the official preference of the “Native Inhabitants of Guam” regarding Guam’s political relationship with the United States. The plebiscite would include three options: Independence, Free Association with the United States of America, or Statehood.

In 2011, Arnold “Dave” Davis, a non-CHamoru former resident of Guåhan, filed a lawsuit against the Government of Guam claiming that his inability to register on the Guam Decolonization Registry was a violation of his rights under the US Constitution. Davis argued that the rights entitled to him through the Organic Act of Guam and the Voting Rights Act were being violated by the native inhabitant clause. Attorney Julian Aguon, however, argued that the distinction being made regarding voter eligibility for the plebiscite was political rather than race-based; therefore, it did not violate federal voting rights and equal protection laws. The district court held that the plebiscite qualified as an election because it would be of interest to every resident of Guåhan. The Ninth Circuit Court agreed with that decision. Currently, the Governor’s Office and Attorney General are working to devise a path forward, one which meets the Constitutional requirements while also recognizing the historical (and ongoing) effects of colonization on the lives of the CHamoru people.

In 2016, Guåhan hosted the 12th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture (FestPac). With the theme “Håfa Iyo-ta, Håfa Guinahå-ta, Håfa Ta Påtte, Dinanña’ Sunidu Siha Giya Pasifiku” (“What We Own, What We Have, What We Share, United Voices of the Pacific”), The festival had thousands of participants from 24 Pacific Island nations and territories present for two weeks celebrating the people of Oceania.

FestPac is the largest and most prestigious regional celebration of traditional and contemporary Pacific arts. Its vision is to preserve Pacific traditional arts for future generations and to provide a platform for Pacific people to gather and share their diverse cultural art forms. The original organizers, the Fiji Arts Council and the South Pacific Commission (now known as the Pacific Community), envisioned a festival organized BY Pacific people FOR Pacific people.

FestPac would re-emphasize the importance of traditional art forms, encourage the creation of new forms of artistic expression, promote the use of Indigenous languages, raise awareness, and celebrate the rich cultural heritage of Pacific islanders. FestPac is one of the few platforms available to Indigenous Pacific Islanders to come together and engage in activities and discussion of issues that affect us all.

Guåhan has participated in the festival since the 1970s. Aside from the successful hosting of FestPac in 2016, it was also an opportunity to think about Guåhan’s political status and led some delegation members to strongly call for Guåhan’s decolonization.

World War II ended for the people of Guåhan in 1944 when the US recaptured the island after 32 months of Japanese occupation. For most war claims against the Japanese, including Guåhan’s, the US appropriated funds for settlements after World War II. However, for the next seven decades CHamorus made many attempts through US Congress to resolve other war claim issues and disparities while the number of war survivors continued to decline.

Since 1977, Guam Congressional Delegates Antonio Won Pat, Ben Blaz, Robert Underwood, and Madeleine Bordallo carried on the effort with proposed legislative action in Congress for the US to provide war claim parity and justice to the people of Guåhan. Fourteen Congressional bills were introduced to establish a Commission to review the history and results of the Guam Meritorious Claims Act of 1945 or provide additional recognition of loyalty and war claim compensation parity but were unsuccessful. Finally, in 2016 the US Senate passed a bill and President Barak Obama signed into law legislation that would allow for war reparations for Guåhan.

In 2017, the US Justice Department’s Foreign Claims Settlement Commission sought approval from the Office of Management and Budget to gather information from as many as 5,000 people and estates in Guam to decide claims for compensation. War claims would be paid to those who were killed, injured, or subjected to forced labor, march, or imprisonment during the Japanese occupation. By January 2020 payments were made to the first of over 3,700 claimants submitted to the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission.