Fanohge CHamoru Put I Tano-ta: Charting Our Collective Future

Table of Contents

Share This

In many respects the people of Guam are hoping to come full circle to a point in our history where we are in control of the direction of our island once again. This desire need not be feared as an attempt to exclude prosperity and liberty to all island residents. Nor should it be viewed as a rejection of a continuing relationship with our country. It should be viewed as a celebration of choice—of democracy—and an opportunity to achieve the potential that exists for all free people everywhere.

The Guam Commission on Self-Determination

Washington, DC, 1988

In 2013 Guampedia launched a new section that included twenty new entries and a slew of historical documents that highlighted the major issues, challenges and accomplishments related to Guam’s political history. Initially given the generic title “Guam Governance,” the section eventually was renamed “CHamoru Quest for Self Determination.” At the time, the pending military buildup and movement of thousands of personnel into Guam, the plans for construction of military facilities for training and operations, and the court case of Davis v. Guam that challenged a plebiscite for Native Inhabitants of Guam to choose their political status brought to the forefront the need for greater awareness and understanding among our community of the island’s political history and quest for greater self-government and self-determination.

Today, Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz is currently under construction in Dedidu (Dededo); Litekyan (Ritidian) is designated a surface danger zone for the Marine Corps’ live fire training range complex, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit has ruled that a plebiscite open only for Guam’s CHamorus would violate the Fifteenth Amendment of the US Constitution. In addition, tensions between the United States, North Korea and China, global warming and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continue to force Guam’s people to question and reevaluate the impacts, expectations and desires regarding our relationship with the United States, the US military, and the Federal Government. At the very least, the issues and challenges have not changed, but the stakes seem substantially higher for the people of Guam.

Since the launch of the section on CHamoru self-determination, a new generation of activists and advocates for Guam’s political, economic, environmental and cultural future has emerged. The pandemic has challenged everyone, from educators to businesses, to find new ways to communicate and present information, or to create or seek out viable economic opportunities. Our island has had to readjust to a new normal in almost every aspect of our daily lives. Guampedia also has had to adjust to this changing world—to develop new approaches and tools to fulfill its educational mission and remain accessible to all.

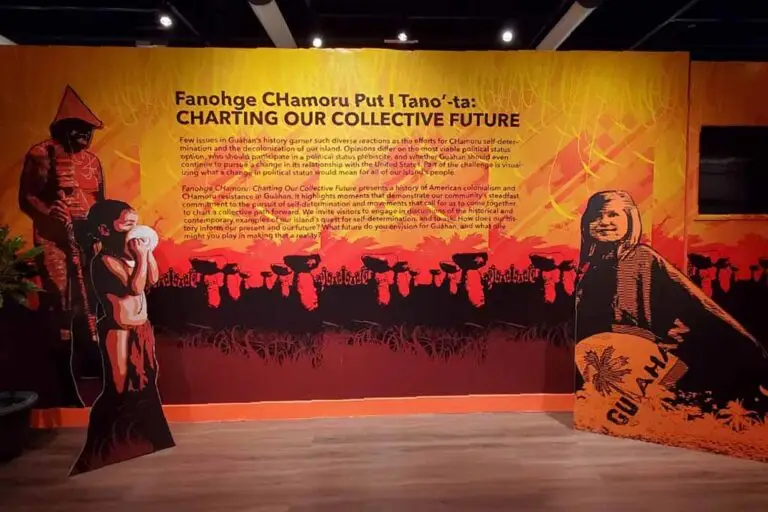

Fanohge CHamoru Put I Tano-ta: Charting Our Collective Future

On 1 August 1950, President Harry S. Truman signed HR 7273 and the Guam Organic Act of 1950 became law. The Organic Act came after 52 years of American colonialism in Guam. It put an end to military rule, granted American citizenship, and declared Guam to be an unincorporated territory of the United States. It established the Government of Guam, contained a Bill of Rights, and outlined the protections and application of federal laws to Guam. Later amendments to the Organic Act modified, clarified, deleted and added provisions to meet the changing needs of the territory. By the 1970s, Guam was able to elect its own Governor and non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives. These were major steps toward self-government. However, the Organic Act is not perfect. The people of Guam were not consulted on its passage in 1950. It does not grant full self-government or equal citizenship for Guam’s people. Guam still lacks power over key matters such as land, immigration and the military presence.

CHamoru scholar James Perez Viernes has pointed out, “written histories and popular understandings of the Organic Act have often characterized it as a generous gift from the US to the people of Guam…More recent histories, however, have begun to show that the Organic Act was achieved through decades of political mobilization among the indigenous CHamoru population rather than through military and federal intervention.” This history of political mobilization is the focus of the recent exhibition Fanohge CHamoru Put I Tano-ta: Charting Our Collective Future.

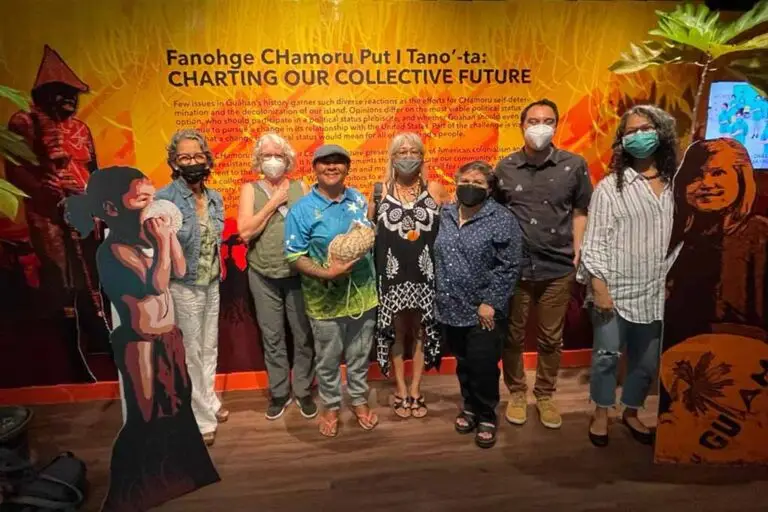

Fanohge CHamoru opened 28 March to 31 May 2022, at the Guam Museum. The exhibition was a collaborative effort between Kevin Escudero, PhD, a visiting scholar from Brown University, Guampedia, the Guam Commission on Decolonization, Department of CHamoru Affairs, and the Guam Museum. Odyessa San Nicolas generated the graphic design and layout. Drawing inspiration from the Guam Hymn and the Inifresi, from aspects of CHamoru cultural heritage and traditional values, and from artwork by artist Kie Susuico, Fanohge CHamoru highlighted the events and people from 1898 to the present that actively engaged in the effort to bring greater self-government for the people of Guam. It was the first such public exhibition that extensively presented this period of Guam’s political development. Through artwork, objects and archival materials from the Museum and private collections, the exhibition presented the central challenges and related issues surrounding CHamoru cultural identity and indigenous rights of Guam’s people as congressional US citizens. The exhibition also encouraged visitors to ponder important questions about Guam’s political status and imagine a future for the island community as a whole.

Fanohge CHamoru Put I Tano-ta was made possible through a grant from the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) and funding from Brown University, the Mellon Foundation and the Guam Commission on Decolonization, as well as the Governor’s Education Assistance and Youth Empowerment Grant Program.

In addition to collaborating on the curation and design of the exhibition, Guampedia provided guided tours for hundreds of students and other visitors to help understand and appreciate the complexities of Guam’s efforts toward political self-determination. Although the physical exhibition has closed, Guampedia is extending its life virtually.

Guampedia has created Fanohge CHamoru, an online hub that allows visitors to experience the Fanohge CHamoru exhibition virtually and access educational resource materials from elementary to high school grade levels on its different themes. In anticipation of transitioning Fanohge CHamoru into a virtual exhibition, Tom Tanner and Burt Sardoma carefully captured the entire exhibition—objects, panels, labels, etc.—on film through photographs and video. The pair not only documented every aspect of the exhibition, they also filmed visitors and conducted interviews to capture people’s reactions as they experienced it. While still a work in progress, all the material will be used to develop different components of the virtual exhibition and resources for teachers of history, social studies, and CHamoru language.

Why a Virtual Exhibition?

Fanohge CHamoru had a very short run for an exhibition of its size and scale. By hosting it online, Guampedia is extending the usefulness and life of the exhibition as an educational tool.

Recently, museum curators and educators have explored the potential of virtual exhibitions to showcase collections and enhance visitor experiences. Many exhibitions and collections are already available online. The global pandemic forced many museums to shut down, including the Guam Museum, for most of 2020. Museums used virtual exhibitions to stay connected with their audiences, even when they could not be there in-person.

Guampedia recognizes the possibilities of the virtual exhibition as an online educational resource that builds on the rich information already available on the Guampedia site. Like its physical counterpart, the online version will be curated and presented in a way that allows visitors to easily go through it. Viewers can read selections of narrative, watch the videos and listen to audio presented in the exhibition, and take their time to observe objects and photographs close-up. Fanohge CHamoru will be the first of its kind for Guampedia. It will be an exciting step forward as we explore new technology to make the virtual exhibition a reality.

One Final Note

Designing an exhibition for public display is rarely ever the work of one individual scholar, curator or graphic designer. Like many worthy endeavors, it often takes many hands and minds working together to weave a story that excites, educates, entertains and is pleasing to the senses. Fanohge CHamoru Put I Tano-ta: Charting Our Collective Future represents an example of what can happen when people are willing to share their knowledge, perspectives, experiences and talents in the spirit of inafa’maolek and inagofli’e for the benefit of our entire community. It is in this spirit that we express our heartfelt thanks to all the individuals, organizations and entities for their contributions and support—in big and small ways—that have helped us along this journey. Dangkalo’ na si yu’os ma’ase!!

3D Tour

Fanohge CHamoru Put I Tano-ta: Charting Our Collective Future

-

- Section 1: Introduction

- Section 2: Unpacking Terms

- Section 3: Identifying Roles and Positionality

- Section 4: Timeline

- Section 5: Oral Histories and Intergenerational Conversations

- Section 6: CHamoru Renaissance

- Section 7: Envisioning and Enacting a Decolonized Present and Future

- Section 8: Organic Act

- Section 9: Closing and Acknowledgements

- Fanohge CHamoru Exhibition Video Features