Speaker Joaquin C. Arriola

Table of Contents

Share This

Postwar leader

Joaquin “Kin” C. Arriola (1925 – 2022) was a prominent figure at the forefront of Guam’s legal history. Arriola was one of Guam’s leaders who took part in making the island what it is today. Guam’s current form of limited self-government took decades of vision, calls for justice, and tenacity by local leaders such as Arriola.

These leaders caused the transformative social, political, economic, and other changes of the 1950s, 60s, and beyond that led us to where we are today. They pushed for increased civil rights for the people of Guam, for ending a single-branch form of military government that, as described by Arriola, ruled the island with an iron fist, and for overcoming Navy interference when striving for greater local self-government. The people of Guam owe much to these leaders who often had to fight Congress’s heavy-handed vision of what Guam’s government should be.

Arriola not only lived through transformative times, he was one of a handful who led the way through them. His path started fairly early on in his life. After high school, he sought more than the limited education offered on island in the 1940s, braving the snows of Minnesota to attain a college education and to tie with Carlos P. Taitano to be the second CHamoru/Chamorro to ever earn a law degree. Returning home to Guam, Arriola was the top vote-getter in three elections and served for two terms as Speaker of the Guam Legislature. At the time, the Speaker was Guam’s highest elected official as island governors were appointed by the US President (1950-1970).

Champion of Guam’s civil rights

As an elected leader, Arriola regularly championed civil rights for the people of Guam when testifying before the United States (US) Congress and when at home. He was pivotal in ending 20 years of Guam’s governors being appointed by the President and in pushing for the creation of a Guam delegate in Congress. Arriola ran in the island’s very first gubernatorial race, vying to serve as the first governor elected by the people of Guam; it was a time when the island was swept away with “election fever.” Arriola and his colleagues, surrounded by self-determination efforts in our region, saw real potential in changing Guam’s political status and fought hard to make it happen. He and others envisioned and worked tirelessly toward a unified Marianas to reconnect with brothers and sisters of the Northern Mariana Islands as well as a means to attain fuller self-government by having strength in numbers.

Arriola (Familian Arrot) was born to Maria Soledad Camacho and Vicente Fernandez Arriola in 1925, a time when the people of Guam had no citizenship nor civil rights. He was the eldest of his seven. Much of Arriola’s life has centered around Hagåtña. He grew up there, attended school there, and worked nearly his entire career there as a Congressman (what those serving in the Guam Legislature were called in the early days), a two-term Speaker of the Guam Legislature, as Guam Legislature legal counsel and parliamentarian, as an attorney of law, and as an Associate Justice for Guam’s Supreme Court (1996-1999).

Education was a priority

Joaquin, along with one brother and two sisters, graduated from college, at a time when having one child with a college degree was a rare accomplishment. The island, according to Arriola, was quiet in those years with not a lot of opportunity. For example, at the time, CHamorus and locals who joined the US Navy were, along with other non-white service members, relegated to serving as mess attendants without any real chance to advance. Arriola finished his college education in record time, just three years, graduating with honors, cum laude. That was quite a triumph, especially given that his high school education was interrupted by World War II (WWII) and lacked substance when it resumed after the war.

Arriola’s children have followed in his footsteps, graduating from universities such as Vassar, Smith, and Rutgers, two of whom became attorneys and became part of the law firm he founded.

Arriola saw the importance of building up Guam’s higher education. He served as Chairman of the Board of Regents for the College of Guam (1963-1966), predecessor to the University of Guam. While some, such as Guam’s first appointed District Court Judge, Paul D. Shriver of Colorado, pointed out to Arriola that the amount of money being spent on building up the College of Guam was enough to send island youth to the mainland instead, Arriola saw that the people of Guam needed some level of independence, something of their own to be proud of, and an institution that would produce good teachers locally instead of contracting them year after year from the mainland at great expense.

The difficult war years

Arriola had been the tender age of 16 when Guam was invaded and conquered by enemy Japanese forces (1941-1944). While much of the wartime occupation did not change life too much for many, as time went on, it became a harsher and harsher existence. Before the end of the war, Arriola lost his mother. Along with hundreds of others, he worked in a coral pit in Anigua and helped build airstrips in Orote and Tiyan, receiving just a handful of rice and a slice of daigo for sustenance. Fortunately, people shared food with one another and his grandfather had a sizable farm in Tiyan. He considers himself lucky to not have had to look too hard for food, an important consideration given the increasing scarcity of nourishment during the occupation.

Shortly before the US recaptured Guam, the Japanese ordered people in his area to march to Manenggon. While Arriola had not heard of the atrocities occurring in Germany and elsewhere, he had a feeling that nothing good was going to happen at Manenggon so, without telling anyone, he chose not join his family on the march but instead took off with a machete.

He survived by keeping out of sight but did go to bring his family food and visit them on occasion. The last time he arrived at Manenggon, there was no one there that he could see. He found a Japanese rifle and a squad of the 77th Infantry Division of the US Army carrying out a cleanup operation. Arriola ended up serving as a guide for them. This stint was short-lived however, as he was hit by shrapnel from a hand grenade that flew out from a bunker they passed. From there, he was taken to the hospital where he met a well-known figure on Guam, Beatrice Flores (later Emsley), who the Japanese had tried to behead and had buried alive.

After Arriola was released from the hospital months later, but before the island was cleared of the dangers of Japanese snipers and others who were roaming the island by the thousands, Arriola stayed in a shack in Mangilao rather than being confined at a refugee camp. For over a year, soldiers, the Guam Combat Patrol, and everyday people of Guam, worked to make the island safe for everyone from the stragglers. Along these lines, while in Mangilao, he sent a Japanese officer and soldier who came across him to, as Arriola stated, “meet their ancestors.”

Numerous decades later, a feeling of bitterness continued for Arriola and many others on the island. The US gave away the people of Guam’s right to make war reparation claims against Japan while at the same time, never fully lived up to its obligation of providing war reparations to the people of Guam, despite the fact that the US has done so for all other populations so affected. War reparations, according to Arriola, have been “so little, so late,” with the great majority of the wartime survivors having passed away before their sufferings were addressed.

Returned to a changed island

Arriola diligently pursued his college education and did not return until his education was completed in 1953, even when his father passed away during his first year of law school. It was too costly to return home. Having left prior to the passage of the Organic Act of Guam which replaced the military government with a civilian government, provided the people of Guam Congressional US citizenship, and established a democratically elected Guam Legislature, Arriola returned to an island that was changed.

Arriola described it as having increased “freedom of sorts.” However, the island, which had been closed prior to WWII, was still to be closed for nearly another 10 years after his return in 1953, which held back economic development and other progress for the island.

Talo'fo'fo Five!

Arriola is also a musician, playing the church organ when he was younger, and the piano. His musical talent helped him earn the money to pay for his higher education in Minnesota. After the occupation, he played in a band called Talo’fo’fo Five. Laughingly Arriola stated that it was a great name which caught people’s attention despite, or perhaps to some degree because, there were only four members of the band, none of whom were from Talo’fo’fo.

Arriola Law Firm established

There were not many lawyers on the island at the time of his return, so Arriola soon found himself busy taking cases and established what is now known as the Arriola Law Firm, Guam’s oldest law office. Over time, he became a member of the American, International, Minnesota, Guam, and Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands bar associations and was admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of the State of Minnesota, the US District Court of Guam, the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit Court, the US Supreme Court, the US District Court of the Northern Mariana Islands as well as their Supreme Court and Superior Court.

Additionally, Arriola was also recognized by the High Court of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands while it existed. Many of Arriola’s accomplishments were firsts for CHamorus and Guam. For example, he was the first CHamoru to achieve being duly admitted and qualified as an Attorney and Counselor in the highest court in the nation (the US Supreme Court).

Arriola captured the attention of the community pretty quickly upon his return home by litigating some high profile cases such as those in which a Hawaiian businessman was charged with embezzlement, a Filipino actor who resided on Guam was charged with adultery as a felony, and a person charged with first degree murder.

Served as a Senator

Before too long, Arriola was asked to run for elected office. Arriola served in the 3rd and 4th Guam Legislatures as a Kongresista (Congressman) as they were so termed at the time, as well as in the 5th through the 7th Legislatures as the legislative legal counsel and parliamentarian, and as legal counsel for the Minority in the 8th legislature. Arriola was then, once again, asked to run for office, having been the top vote-getter in the 4th legislature. Being a top vote getter for the 9th and 10th legislatures, he also was selected to serve as Speaker.

Arriola attributes some of his popularity to people’s appreciation for representing them in the disturbing land cases of the time, in which massive tracts of prime, locally-owned, family land had been condemned by the military-run government in order to rebuild the war-torn island in a manner that often pushed CHamorus and others aside to meet the Navy’s perceived needs.

Guam is an indigenous homeland, and is a place where land has deep meaning and familial ties. During this time, the military condemned as much as 63 percent of the island. Some who had their land seized never cashed the paltry checks they received as compensation. Many were angered by these land takings, anger which lingers decades later as much of the land has yet to be returned. Arriola was able to get his clients more favorable compensation for their land although it was difficult to do so since the island was closed, meaning that there was no real market value for the land to hold the government to. To his credit, Arriola handled more of these land cases than any other lawyer.

The early legislators had many injustices to resolve—having an island governor with extraordinarily broad authority be appointed by the US President, having the legislature’s authority to override a governor’s veto be curtailed by having their override be sent to the US President who could then overrule their override, and being a territory which is not meant to be a permanent political status.

Fought for more self-governance

Several times during his terms as Speaker, Arriola represented the people of Guam by testifying before the US Congress. Arriola provided powerful statements arguing for the importance of having a democratically elected governor but against a federal comptroller to oversee the government of Guam. He and others believed in accountability and transparency, offering time and again to be audited by the Government Accountability Office but rightly saw that the executive and legislative branches of Guam’s governmental authority would be curtailed by having a federal comptroller. Arriola led the opposition to this proposal, calling it in his testimony to Congress, “a definite step backward in Guam’s political development.” As he further testified, other than the territory of the US Virgin Islands, “no state or other territory or possession is saddled with this ‘fourth branch of government.’”

Under Arriola’s leadership, the Guam Legislature passed a resolution supporting this position and took out full page ads in the New York Times and the Washington Post to try to make their opposition widely known. The case was hard fought, meeting with US Congressmen when and where they could, a testament to Arriola and others’ commitment to the people and government of Guam.

Two big issues: Elected governor for Guam, reunification of the Marianas

As Speaker, Arriola had two main agendas—attaining an elected governor for the people of Guam, which was successful, and the reunification of the Mariana Islands, which was not. He and others worked with the Northern Mariana Islands for years when they, as former Micronesian possessions of Japan, were determining their political status within the UN Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, a strategic trust administered by the United States.

Arriola and other leaders created the Pacific Conference of Legislators and the Mariana Islands District Legislature to promote discussions between the different governmental bodies, including discussions about common political status goals. While much progress was made in the Northern Mariana Islands, Arriola reflected that perhaps not enough time had been spent campaigning and educating people on Guam as to how the islands could achieve fuller self-government, perhaps statehood, if they were a larger, stronger, unified archipelago.

Several elements may have been working against this larger vision, including bitter feelings by the people of Guam toward the Saipanese and other men from the northern islands who had been part of the harsh Japanese wartime administration on Guam. Another is said to have been a “whisper campaign” in which people were already aligning themselves for the first gubernatorial race stating that a vote for reunification was a vote for Arriola versus other gubernatorial hopefuls. While people in the Northern Mariana Islands voted to reunify, at the end of the day, the people of Guam did not. Arriola and other leaders had been caught off guard by Guam’s rejection of reintegration after working so long and hard toward that goal and after having perceived that the hearings on Guam were positively received.

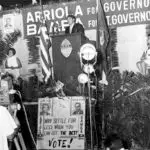

Gubernatorial runs

Arriola ran for governor in both the first and second gubernatorial races in 1970 and 1974 respectively. The campaigns in these early years were very active. In his first run, his slogan was, “JCA is the ONLY way!” He ran with retired judge and senator, Vicente Bamba, who balanced Arriola’s youthful vigor by being a bit older and having years of experience as a judge. Since most of campaigning in those days was about meeting people, Arriola-Bamba canvassed houses and held district meetings. Groups were formed like Young Citizens for Arriola-Bamba (YCAB) and Ladies for Arriola-Bamba. Rallies at their campaign headquarters, immediately adjacent to the Guam Legislature building, or at one of their homes could go late into the evening, being entertained by bands and their campaign cheerleading squad.

While Arriola-Bamba gave it a good run, and had been considered to have had a strong chance being two very popular candidates, what perhaps worked most against them was their late declaration to tackle immigration, or what was termed, the “alien issue.” Although Arriola-Bamba were vocalizing very real worries and concerns that existed within the community about CHamoru loss of control of their homeland due to the large, rapid shifts in island demographics that were happening at the time, the media and some within the community pushed back against the issue. In the end, Arriola’s bids for governorship were unsuccessful though people have stated that they thought he would have made a fine governor.

Marriage and family

In 1954, Arriola married Elizabeth Perez Arriola and together they had eight children–three daughters (Jacqueline, Anita, Lisa) and five sons (Vincent, Franklin, Michael, Joaquin Jr., and Anthony). Elizabeth followed in her husband’s footsteps becoming a six-term Guam senator making them one of the few couples on Guam to have both served as senators in the Guam Legislature.

Arriola litigated hundreds of cases, civil and criminal, on Guam and abroad, including for the US District Court of Guam, the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit Court, the US Supreme Court, the US District Court of the Northern Mariana Islands as well as their Supreme Court and Superior Court.

Community service

All the while, Arriola continued to hold numerous leadership positions within the community at a level which few attain. He served as President of the Guam Bar Association. He was Chairman of the Territorial Planning Commission, the Guam Housing and Urban Renewal Authority (GHURA), the Board of Regents, the Popular Party and, later, the Democratic Party, as well as was Executive Committee Chairman for the Pacific Conference of Legislators among other such positions. He has often been a keynote speaker at events and has won numerous awards and recognition such as the Guam Judiciary Husticia Award and the Judge Cristobal C. Duenas Excellence Award, as well as was conferred a Doctor of Laws (Honoris Causa) by the University of Guam.

When Arriola retired in 2021, alongside other accolades, both Governor Lou Leon Guerrero and the Speaker Therese Terlaje recognized him with a Governor’s Award and Legislative Resolution, both of which noted the Honorable Joaquin C. Arriola as having been “at the forefront of Guam’s legal history as a highly respected lawyer in the Guam and CNMI courts for 67 years.”

Arriola held numerous other important roles as well, at times dealing with multi-million dollar transactions. For many years he served as Board Member, Secretary, and Counsel for Guam Savings & Loan Association (BankPacific), local counsel for Bank of America, and even helped form and organize the Bank of Guam which he then served as its general counsel. He was local counsel for off-island corporation such as ESSO Eastern (Exxon) and AT&T, he organized and formed domestic corporations like Hotels of the Marianas, Inc (Hilton Hotel), and represented individuals and corporations in various locations around the world.

Life's highlights

Over the years, Arriola met with the likes of US Senator Ted Kennedy, famous actress Tita Duran, and more. He saw his island change from a military government to a civil one with, although limited, more self-government than it had ever had in modern times. Arriola played no small part in achieving many of those gains. He has testified before the US Congress as the highest elected official of the people of Guam. He fought for the best interests of Guam’s people against development of an ammunition wharf at Sella Bay and, known for making bold statements, said, “Hell no,” to nerve gas being stored on Guam. He lived through the US civil rights movement, national conflicts and wars, the assassination of a president, the landing of the first man on the moon, the coming and going of UN missions in our region, the rise of the Brown Power movement in the states and in Guam, an attempt at commonwealth for Guam, and the attainment of commonwealth and independence for neighboring islands.

Arriola stated that he has had a great life in which he “has seen it all, good and bad.” Given the weight of his responsibilities over his lifetime and how busy his positions kept him, Arriola expressed wishing that he had spent more time with his children when they were younger but noted that he worked to make up for that later in life by spending time with them and his grandchildren.

Arriola’s legacy will continue through the impact he has made in his numerous leadership positions, his lifelong advocacy and struggle for increased civil rights for the people of Guam and improved self-government, the laws that he passed that helped shape and strengthen the Judiciary as well as the many causes that he championed.

e-Publication featuring Speaker Arriola

Videos: Interview with Speaker Arriola

For further reading

A Bill to Provide for the Popular Election of the Governor of Guam, and for other Purposes. HR 7329. 90th Congress, 2nd Session, 45-111 (1968) (testimonies by Joaquin C. Arriola, Speaker of the Guam Legislature; Manuel FL Guerrero, Governor of Guam; and Antonio B. Won Pat, Guam Congressman).

Arriola, Joaquin C. “Oral Interview of Mr. Joaquin C. Arriola.” Interview by Lolita C. Toves. District Court of Guam, 20 January 2006.

–––. “Joaquin C. Arriola.” Interview by Dr. Kelly Marsh-Taitano. Modern Guam Rises from Destruction of War: 1945-1970, Guampedia, 22 February 2021.

Guam Commonwealth Act. HR 98. 101st Congress, 1st Session, Part II 36-46 (1989) (testimony by Joaquin C. Arriola, Speaker of the Guam Legislature).

I Manfåyi: Who’s Who in Chamorro History. Vol. 2. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education and Coordinating Commission, 1997.

Sanchez, Pedro C. Guahan Guam: The History of Our Island. Hagåtña: Sanchez Publishing House, 1987.