Pre-colonial art

Discussing the pre-colonial arts of Chamorros is a difficult task. Documents by the Spanish who first made contact with Chamorros are limited. These accounts are incomplete and heavily laden with bias. Mentions are made of certain skills of Chamorros, certain technologies, certain practices, but they are often only mentioned, or they are mentioned and then condemned as savage. Similarly, much of the arts that Chamorros possessed were not passed down after centuries of colonization, or were made from natural materials which have not lasted through time.

From what researchers know from this period however, can nonetheless provide an interesting snapshot of the arts of Chamorros during the first centuries of European contact. The term “art” here refers to skills or goods that Chamorros produced, which did not only displayed Chamorro collective or individual craftsmanship, but also their creativity; something which was produced not only to be functional, but also to be gef pago (beautiful).

Carving

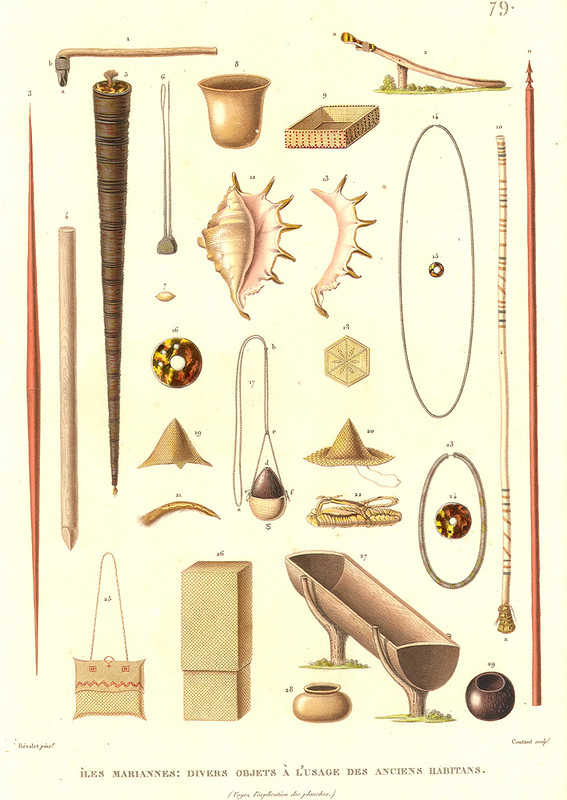

Carving was an essential part of life for ancient Chamorros. By carving håyu (wood), to’lang (bone) and cheggai (shell) they created all the tools which were necessary to sustain themselves. In the things that they carved, is evidence that Chamorros used their skills to show their individual identity and their creativity.

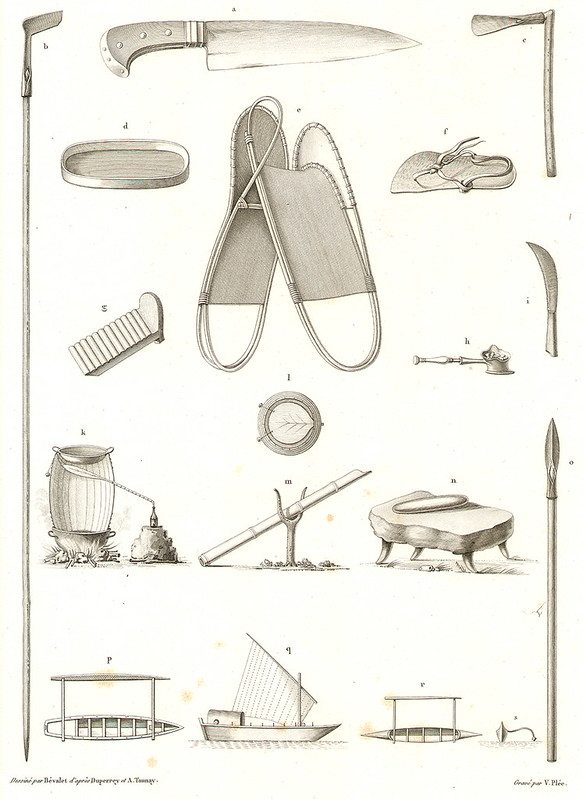

When English explorer Thomas Cavendish visited Guam in 1588, he noted that the ends of Chamorro canoes featured interesting carved figureheads. These figures sported long flowing hair that was tied up once or twice, and stood at the “head of their boates [sic] like…images of the devil.” These carvings might have been modeled after the owner or the navigator of the canoe, or perhaps represented an ancestral spirit who was asked to protect the boat. Although we can’t be sure as to why they were made or whom these figureheads represented, we can be sure that they gave each canoe a distinct identity, that these carvings were meant to not be practical but rather express a creativity and give an identity to each vessel.

A similar creativity could be found in the carving of tunas. A tunas was a tall wooden båston (walking stick) which was carried by all unmarried men or bachelors. These men were called uritao or ulitao. Each tunas was carved and colored in a distinct way, in order to signify to whom the staff belonged. It is speculated that these staffs served a similar function as the Chuukese love stick and provided a way of identifying a bachelor by the carvings on his tunas even if he was absent or unseen.

An uritao who was visiting a woman would leave his tunas outside the door of the home, so that all who came by would know who was inside. A bachelor wooing a woman could poke his tunas through the floor or the wall of her house. If the woman being wooed recognized the carvings or the markings on the staff, she could then reject the advances by pushing the staff away or accept them by pulling the staff in or meeting the uritao outside.

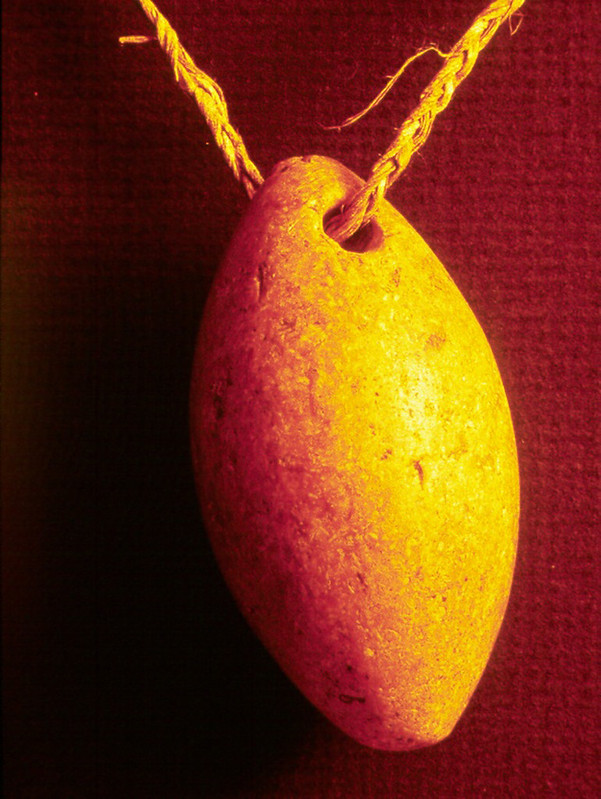

Chamorros also created beautiful forms of alåhas (jewelry) carved from various shells. By using and wearing these works of art, Chamorros could signify their social status or ginefsaga’ (wealth) but also enhance their beauty and individuality.

Story telling

As Chamorros had an oral culture those with a very adept mind, a good memory, a sharp wit or a flair with words were highly regarded. Storytelling, the retelling of family histories, chamorita (improvisational singing) and mari (debate) were all considered art forms, and a master of any of these skills was considered to be as great as a warrior on the battlefield.

Ancient Chamorros held regular large gupot siha (parties) and the displaying of these oratory skills was an important part of the entertainment. Individuals would vie against each other, families would compete and mock each other and sometimes entire villages would become embroiled in debates or displays of who had the better storyteller or singer. According to Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora’s account of these interactions from 1602:

They also get together to hold debates: those representing one side meeting in certain barn-like structures (kamarines), those of the other side in others. One debater will get to his feet and begin to argue, or to make up ballads, or to poke fun at those across from him who are from another village. When the first group has finished, someone from the opposing side gets up and begins to argue against the first side. In this fashion, as I have said, people from many villages get together to debate from eight o’clock in the morning until two in the afternoon, when they eat.

The wisest of the indios gather for these debates, some will have learned the skill, called mari, when very young.

Performance

The other half of the entertainment at these parties, was also taken very seriously and considered to be a form of artistry amongst Chamorros, were physical spectacles of strength and dexterity. At these gupot siha young men would perform different feats such as afulo’ (wrestling) before the highest class members of a village in order to gain respect or favor in their eyes. The account of Zamora also noted that they also competed by hurling spears at each other and catching them in mid-air.

Sometimes they take hard falls. When this happens, the friend of the one pinned underneath comes forth and, with great arrogance, says, ‘Now, you will have to fight me’, and he begins to fight with the victor. In this way, one follows another and some are so arrogant that they say, ‘you are mere children and should fight with children and not with me.’ This is the way they prove their strength. Sometimes they will step away from each other and, although they seem to be jesting, they actually are not, as is true in fencing. At ten or twelve paces, they throw darts at each other and, although their aim is very accurate, they are even more adept at deliberately missing the target and will often snatch the dart in midair. Such as person will say to the one who threw it, ‘Do you think I’m blind? Notice that I have good eyes.’ He then throws it back at him. This is the way they brag before their leading citizens.

In addition to the wrestling and dart competitions, Chamorros also competed in sham fights with a weapon called a fudfud, which was a long wooden pole about five and and a half feet long, with which they would duel.

There are references to dances as well, by both men and women, individually or in linahyan (large groups), which were also considered an important art form amongst Chamorros. The particulars of the these dances were not well recorded and traditional dancers were eventually prohibited by the Spanish missionaries. However there are a few brief historical descriptions of ancient Chamorro dance. Rose Freycinet, wife of French explorer, Louis Claude de Freycinet, kept a journal describing Chamorro dancers in 1819 as moving “first in groups and in circles, gesticulating and contorting themselves to a rather slow tune.” Michael Clement Sr. made note of references to Chamorro dances in a report by Father Francisco Garcia in 1683, as derived from early Jesuit missionary notes. European explorer Jules-Sebastien-Cesar Dumont D’Urville‘s refers to a Chamorro “Dance of the Ancients” which Clement conjectures may have been a reference to performances of the Puntan and Fu’una creation story. Louis Freycinet noted in 1819 that the hand and body gestures in Chamorro dances were a way of clarifying word meanings.

The historical literature also contains several references to Chamorros dancing the “Dance of Montezuma” that at least by 1819 had been performed for visitors by students from the Colegio de San Juan de Letran using Mexican costumes that had possibly been preserved by Jesuits until their expulsion from Guam in 1769.

Weaving, rope and banner making

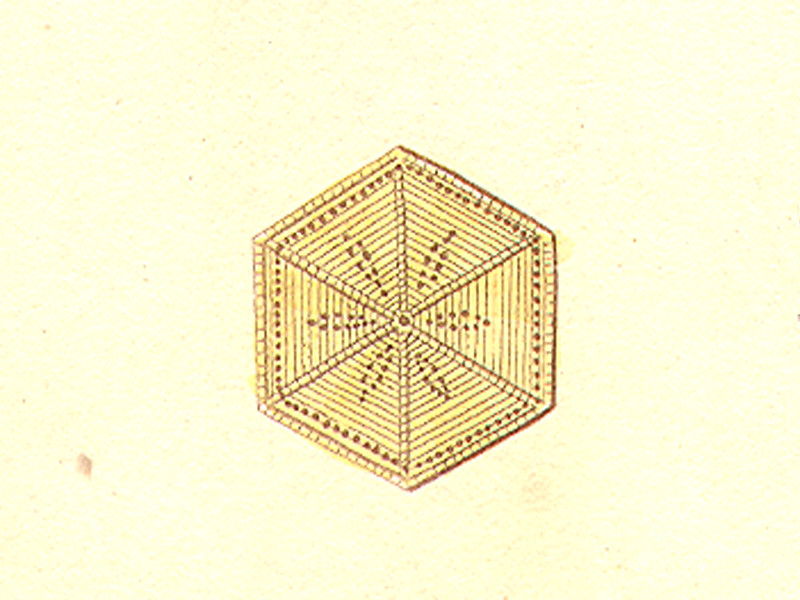

The weaving of akgak (pandanus), hagon niyok (coconut leaves) and also the making of tali’ (rope) was also an important skill that ancient Chamorros used to survive, which also had some aesthetic and creative qualities. Ceremonial outfits such as skirts, headbands, sashes or belts would be woven and sometimes adorned with shell beads or flowers.

One of the most distinct and visible ways in which Chamorros wove things creatively was in the making of large akgak babao, or banners. Large banners would be used by men returning from a voyage or a fishing trip to communicate whether their journey had been a success or a failure. These babao were also essential in wars that would break out between families or villages. Warriors would carry into battle with them a banner representing their family, ancestors or village. When Freycinet visited Guam in 1819, he was told that the Chamorro name “Babauta” meant “he who defended our banner.” In modern Chamorro the name translates to “our banner.”

Much of the visual arts of Chamorros, especially that which involved painting, did not survive the centuries due to its being created with perishable materials. Chamorros made pigment for paints from afok (quicklime), red earth, charcoal, breadfruit sap, and låñan niyok (coconut oil). The colors of agaga’ (red), å’paka’ (white) and åtilong (black) were painted prominently on the canoes of the time. Chamorros also painted images of their ancestors in pieces of bark and wood and kept them in liyang siha (caves) called guma’alumsek. No examples of these forms of artistry survived.

Cave drawings

The only examples of Chamorro painting that have survived are pictographs and petroglyphs found in liyang siha (caves) throughout the Mariana Islands. Petroglyphs are made by first scratching the surface of a wall and then painting into the incisions. Pictographs are made from paint applied directly to the wall surface. The types of imagery that Chamorros painted varied based on what the paintings were meant to convey. Some pictographs such as the famous paintings in Gadao’s Cave in Inalåhan, Guam, are now used as identity symbols referring to ancient people of the land the “taotao tåno”. It is not known what the symbols represent, but a recent theory is that they could represent the famous battle between Chief Gadao of Inalåhan and another from Tumon. Other paintings seem to recount family or historical events, or perhaps were painted to record an event of significance or even provide directions to good hunting or fishing sites.

Some figures are drawn taiulu (without heads) and were most likely meant to be ancestral spirits. It is possible then, that in addition to recounting past events, these drawings might have been made in order to affect current or future events. A painting of a man riding in a canoe might be a story of someone who travelled far or caught many fish, but it could also represent an attempt to communicate with the spirits of Chamorro ancestors and to ask them for protection or help in ensuring a safe voyage or menha (a good catch).

Although tattoo is a common artistry in other Micronesian Islands (such as Yap, Belau and the Marshall Islands) and other islands in the Pacific, there is no evidence that Chamorros participated in this art. Explorers did notice one type of bodily art that Chamorros, in particular Chamorro women used and archeological evidence has further supported its existence. In order to beautify themselves women would stain their front upper nifen (teeth) with pugua’ or other plant juice in order to blacken them. There is also evidence of Chamorros scratching marks into their front nifen.

By Michael Lujan Bevacqua, PhD

For further reading

A Journey with the Masters of Chamorro Tradition. Hagåtña: Guam Council on the Arts and Humanities Agency, 2000.

Clement, Michael R. “The Ancient Origins of Chamorro Music.” MA thesis, University of Guam, 2001.

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation. Tiempon I Manmofo’na. Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. By Scott Russell. Micronesian Archaeological Survey No. 32. Saipan: CNMIHPO, 1998.

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.

Flores, Judy. “Art and Identity in the Mariana Islands: Issues of Reconstructing an Ancient Past.” PhD thesis, University of East Anglia, 1999.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

Freycinet, Rose Marie Pinon de. “Health and Courage Restored.” In A Woman of Courage: The Journal of Rose de Freycinet on Her Voyage Around the World, 1817-1820. Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1996.