Japan attacks the island

Saburu Kurusu, diplomatic pouch in hand, stepped off the Pan American Airways Clipper at Sumai while rumors persisted in Guam that war with Japan was imminent. But news reports elsewhere were saying that the Washington-bound Kurusu, special envoy for Emperor Hirohito appointed by the Japanese imperial government, was enroute to peace talks with high American officials.

It was November 1941. Japan’s imperial soldiers were administering Japanese influence in Manchuria and aggressively expanding south into more of China. Adolf Hitler had grabbed much of Europe and his forces locked in battle with the Russians.

Then, a month later, it happened. Guam was struck by disaster on 8 December 1941. Out of the east that morning came nine Japanese planes flying high at first, then swooping down like vultures, their guns spitting death and destruction. Just four hours earlier, Pearl Harbor was attacked with more than 2,500 Americans killed and America’s proud Pacific Fleet badly crippled.

In Washington, Kurusu was still talking peace; he was unaware of the Japanese military’s plan to strike at Pearl Harbor. In Guam, terror gripped the people as the warplanes, flying in formation of threes, bombed Sumai and later strafed Piti, Hagåtña and other populated areas.

The date was the Catholic Feast of the Immaculate Conception and many families were still in church when the planes struck. The city of Hagåtña, the hub of the island, was instantly transformed into a city of shocked people. Mothers and children wept and wailed. Fathers sought missing members of their families in efforts to flee from the town.

Among the first victims of the attack were Teddy Cruz and Larry Pangelinan, young Chamorro kitchen workers who perished when a bomb hit the Pan American hotel at Sumai. Also killed was Ensign Robert White, who manned an anti-aircraft gun aboard the USS Penguin. The vessel, the only seaworthy ship in Guam at the time, fought the Japanese aircraft off Orote Point, but to no avail. The Penguin commander then decided to scuttle the ship.

By the end of the day, the feast that was to be was transformed into the beginning of one of the most tragic periods in the history of Guam. A day later, the planes returned for more, again striking military facilities and the Pan American Airways station.

Then, on 10 December, Japanese forces invaded Guam by shore, more than fully prepared for the undertaking. By mid-October, the Japanese 18th Air Unit, a small force of reconnaissance seaplanes, had begun survey flights over and near Guam. By November, the unit was flying secret photo reconnaissance missions over the island at altitudes of 3,000 meters or higher.

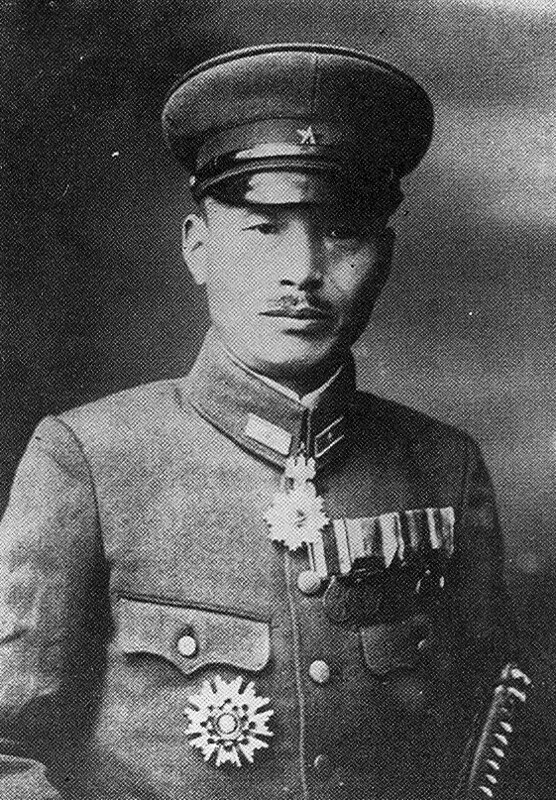

Assigned to capture Guam was the South Seas Detachment, a unit of about 5,500 army troops under the command of Major General Tomitara Hori, and a special navy land force of about 400 men led by Commander Hiroshi Hayashi and drawn from the 5th Defense Force stationed in Saipan.

The Guam defending force was woefully under gunned: 274 Navy personnel, more than half of them non-combative personnel; 153 Marines; and about 120 Insular Force Guards, whose military training was minimal at best.

The Guam defenders’ total arsenal were three machine guns, four Thompson submachine guns, six Browning automatic pistols, fifty .30 caliber pistols, a dozen .22 caliber regulation rifles, and 85 Springfield rifles. Most of the weapons were of World War I vintage. Imprinted on the Springfield rifles were labels with the following notation: “Do not shoot. For training only.”

The outcome of the invasion was certain in terms of firepower. The scenario in the early morning of 10 December 1941, was this: a 400 strong, a well-trained and well-disciplined Japanese invasion force landed on Tamuning’s Dungca’s Beach; the larger invasion force of 5,500 made beach landings around the island – in Tumon, in Yona at Togcha, between Facpi Point and Malesso’/Merizo. This group in southern Guam, finding no road to Hågat, was forced to re-board their supporting craft and re-landed in Hågat.

The invaders at Dungca’s Beach, after regrouping, made their way to Hagåtña, through the jungles and barrios (neighborhoods) along the way to the town. Somewhere in between, the troops ran into a group of Chamorro families, fleeing the area in a small bus. The troops fired their weapons – the shots were heard in the Plaza de España in Hagåtña where a defending force had mustered and established its fields of fire. Those not killed were bayoneted; 13 men, women and children perish. Still other chance meetings with local people result in deaths; an unknown number of people were killed.

At the plaza, a small contingent of Insular Guardsmen, a few sailors and Marines had taken their assigned positions and awaited the invaders. (The bulk of the Marines were assigned a defensive position at Orote peninsula near the firing range.)

In spite of the odds, the defenders in the plaza seemed spirited. Pedro Cruz, one of the three platoon leaders who manned the machine guns, perhaps best expressed the sentiments of Guam’s defenders:

The only thought in my mind was: If I must die, I hope to God I kill some Japanese.

The battle lasted less than an hour, and ends only after Governor George McMillin realized the futility of the situation. At 7 am on 10 December 1941, Guam was surrendered. Dead in the fighting at the plaza and in small incidents around the island were twenty-one US military personnel and civilians. The Japanese, though superior in force, apparently suffered more casualties.

With the surrender, Guam, Wake Island and two isles in the western part of the Aleutian Islands chain, Kiska and Attu, would be the only parts of the United States to be occupied by enemy forces in World War II. (The Alaskan isles are taken by the Japanese in mid-1942 and recaptured by US forces a year later.)

Japanese officials immediately issued a proclamation informing the populace that their seizure of Guam was:

For the purpose of restoring liberty and rescuing the whole Asiatic people and creating the permanent peace in Asia. Thus our intention is to establish the New Order of the World.

The local population also were assured that :

You good citizens need not worry anything under the regulations of our Japanese authorities and may enjoy your daily life as we guarantee your lives and never distress nor plunder your property…

For three months after the Japanese invasion, Guam was a veritable military camp. Soldiers and other military personnel traveled to Guam, coming primarily from Saipan and Palau, both islands occupied by Japan since the end of World War I. Under the Minseisho, the civilian affairs division of the South Seas Detachment, some 14,000 Japanese army and navy forces took over all government buildings and seized many private homes.

Troops were stationed in various parts of the island, a dusk-to-dawn curfew initiated; cars, radios, and cameras confiscated.

Sumai villagers evicted

In Sumai, the island’s commercial center, all of the 2,000 residents were evicted from their homes. Some, however, were given permission to dismantle their homes and many people built temporary shelters at nearby Apra and other farm areas. But still, the small, bustling community adjacent to Apra Harbor vanished almost overnight.

In many instances, Japanese soldiers moved into private homes without notice or formality. Members of the family of Juan Cruz, a carpenter, were having lunch in their kitchen when armed Japanese soldiers ordered them to get out of the house. The family members gathered the food on the table and collected whatever utensils they could carry, and moved to an unoccupied house nearby where they finished their meal. Leon Gumataotao and his family were forced to surrender their concrete house, and had to build a wooden-framed house nearby. There were also abuses of the people; as the Japanese moved to take Sumai, soldiers raped five young women.

To impress upon all that they meant business, Japanese authorities executed two young Chamorro men before a group of stunned residents of Hagåtña. Killed were Alfred Flores, who was accused of delivering a secret message to an American internee, and Frank Won Pat, an employee of an American company, from whose warehouse he helped himself with some goods, after obtaining permission from his American supervisor. Flores’ message sought advice on what to do with a batch of dynamite at a worksite at the harbor.

About one-fourth of Hagåtña’s residents returned from hiding but the great majority chose to stay away from the village. The historic Dulce Nombre de Maria Cathedral was converted into a propaganda and entertainment center, and a church building in Santa Cruz became a workshop and stable for the Japanese’s Siberian stallions. The island’s Baptist church, also in Hagåtña, was also seized; Japanese officials used the first floor of the church as a storage area for food, and the second floor was utilized as a Shinto shrine.

Passes required

All local residents were required to obtain passes – a piece of cloth with Japanese characters – in order to move about the island. All local officials, including municipal and village commissioners and policemen, were ordered to return to work.

Dozens of men, particularly members of the Insular Force Guard, were interrogated and beaten during the first few weeks of occupation. Many were suspected of either hiding machine guns or other weapons, or of harboring American fugitives.

Prisoners taken away

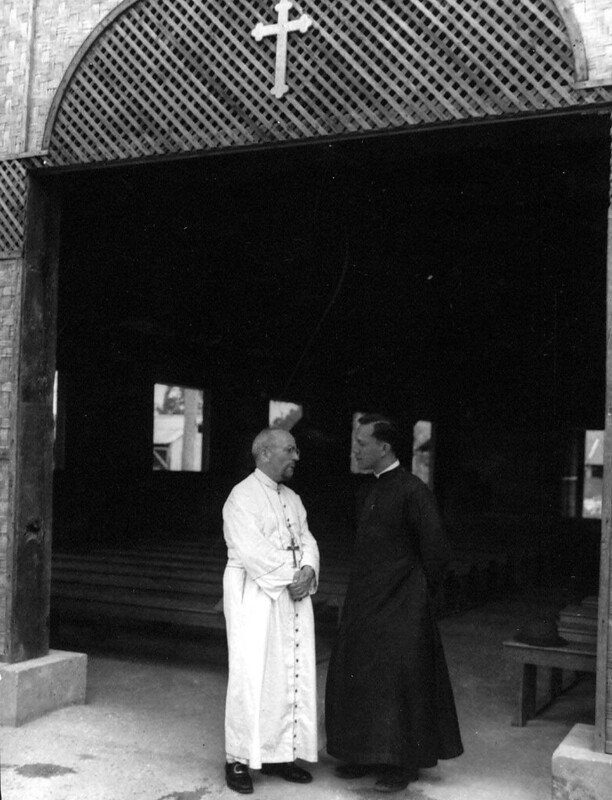

Japanese military officials were intent on erasing from Guam the influence of the United States and thus immediately imprisoned Governor McMillin, other US citizens, as well as some Spanish clergy, notably Bishop Miguel Olano, head of the Catholic church in the island.

The prisoners were exiled to camps in Kobe, Japan. When the Argentina Maru sailed from Guam on 10 January 1942, aboard were 483 people – military personnel, five nurses and a number of civilians. All Americans prior to the invasion were accounted for except six Navy sailors: Al Tyson and George Tweed, both radiomen first class; A. Yablonsky, yeoman first class; LW Jones, chief areographer; LL Krump, chief machinist mate; and CB Johnston, machinist mate first class. Without exception, the six sailors believed the war would not last more than three months and they felt they could survive in the dense jungles of Guam until the Americans returned to the island.

Only Tweed survived the war, thanks to the dozens of people who harbored him during the 30-month occupation period. Krump, Jones and Yablonsky were discovered in the Manengon area in September 1942 and were beheaded by the Japanese. Two months later, Tyson and Johnston were found and shot in Machananao.

Comfort women brought in

The Japanese government, besides its troops, also dispatched “comfort girls” to the island. Five homes were selected to house the women, three in Hagåtña, one in Anigua, and one in Sasa, a farming area near Piti.

The invasion detachment departed Guam 14 January 1942, sailing to Truk (now Chuuk) with carriers and other ships of Japan’s 4th Fleet; this force would later take Rabaul and make it one of the empire’s major military bases in the Pacific.

Left to administer Guam was the Keibitai, the Japanese naval militia with less than 500 men. Directly managing the people were the Minseibu, the Keibitai’s cadre of policemen and investigators. Under the Minseibu, life on island was relatively quiet.

However, there were still attempts to convince the Chamorro populace of Japan’s superiority over the Americans. After every Japanese conquest in the Pacific or Far East, military parades were held through the streets of Hagåtña. When Singapore fell on 15 February 1942, sabers rattled through the narrow streets of the barrios of San Ignacio and San Nicolas; the march of soldiers would end at a Buddhist shrine on a hillside above Hagåtña. Other shows of might by the Japanese military were given when General Douglas MacArthur fled to Australia from the Philippines and later when General Jonathan Wainwright surrendered that archipelago on 6 May 1942.

In these parades, invariably at least one float showed a young boy attired in Japanese army uniform pointing an over-sized rifle at the heart of another youngster wearing an American naval uniform. Spread on the floor of the float was an American flag, and one foot of the Japanese-clad youngster was stepping on it. And to make the occasions even more festive, at least for the occupation forces, sake was made available afterward to those in the parades.

While many Chamorros believed the war would last no longer than 100 days, the Japanese came to stay at least 100 years. Accordingly, the new rulers brought school teachers, along with their families by the middle of 1942, and on the following November, two Japanese Catholic priests came to the island to help pacify the local people.

Soon after the invasion, the Japanese authorities acted to battle a shortage of medical personnel. Training began and Chamorros did assist Japanese nurses and doctors, but eventually, the language difference and other factors lessened the program’s effectiveness.

Island, villages renamed

Among the first things the new rulers imposed was the renaming of the island and all municipal districts. Guam became Ômiyajima (Ômiyatô) or “the island of the Imperial Court” by the Japanese Navy. Hagåtña became “Akashi” (the Red City). Asan was “Asama Mura” and Hågat became “Showa Mura.”

The practice of bowing as a sign of respect was instituted and strictly enforced. Essentially, bowing was a sign of respect to another person, an institution or the supreme ruler of the land, the emperor. Bowing to a friend required only a slight nod of the head. Bowing to an officer or to an institution, like a police station, required the bending of the head and body at a forty-five degree angle. The supreme bow, which was reserved only to the Japanese emperor and members of his family. This required a person to face north and then bend his entire body forward and down to a ninety degree angle. And in doing so, the person must bow slowly and solemnly.

Schools reopened

By mid-1942, all public schools were reopened and the young students were required to bow to the emperor before classes commenced in the morning. In the classroom, they learned the Japanese language and culture, and mathematics. Children attended school during the week for four hours daily; adults were required to attend two evenings a week. But attendance was less than spectacular; over the occupation period, perhaps only 600 children and adults participated in the Japanese-run schools.

As part of the educational program, Chamorros were also taught songs, some of them Japanese patriotic songs, but there was one very popular song that the occupying authorities detested and even punished people for singing.

Though forbidden, both children and adults learned and sang the song throughout the occupation period – it was a ditty urging the return of the Americans. One version went like this:

Eighth of December 1941

People went crazy

right here in Guam.

Oh, Mr. Sam, Sam

My dear Uncle Sam,

won’t you please

come back to Guam.

Communication restricted

Although possession of a radio was strictly prohibited, a number of Chamorros were daring enough to operate radio receivers throughout most of the occupation period—until about late in 1943 when American forces were pummeling the Japanese in the south and central Pacific.

Members of the underground radio network included Jose Gutierrez, Augusto Gutierrez, Frank T. Flores and Atanacio Blas; Adolfo Sgambelluri, Mrs. Ignacia Butler, Ralph Pellicani, Carlos Bordallo, Juan and Agueda Roberto, Manuel FL Guerrero, James Butler, Joe Torres and Herbert Johnston; Agueda Iglesias Johnston; Frank D. Perez, the Rev. Jesus Baza Duenas, ET Calvo; Luis P. Untalan, Jose and Herman Ada, and Pedro M. Ada. The radio receivers had to be destroyed or abandoned after Japanese officials obtained copies of news reports, including the following:

— “Rabaol, (sic) New Guinea — Japanese forces are being hammered in their positions by American Flying Fortresses from Australia, enemy losses: planes 17 downed.”

— “Burma — Flying Fortresses heavily bombed Japanese positions along the Burma Route causing heavy damage, killing many Japanese soldiers. 21 Japanese planes shot down. 2 of our planes returned slightly damaged.”

Most of the radio reports received originated from KGEI, a radio station located at the top of the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. Newscasters included Bob Goodman and Merrill Phillips.

Signs evident that Americans were returning

While Japanese forces were being defeated everywhere in the Pacific – the Solomons, New Guinea, the Marshalls, New Hebrides and the Gilbert Islands – a Japanese freighter at Apra Harbor was sunk by an American submarine, and a second Japanese ship off Talo’fo’fo was struck by another American submarine. The vessel was aflame after the attack. Adrift and useless, the vessel settled at the mouth of the bay, a sign of the attack to Guam.

There were other signs that American forces were nearing Guam. Cristobal Paulino, an Insular Force musician, and fellow Chamorro workers were laboring at the Orote air strip on 23 February 1944, nine American fighter planes swooped onto the runway and blasted away, killing four Japanese and damaging at least four aircraft. By the time Japanese pilots boarded their Zeroes, the American planes were gone.

With the twin American offensives – the MacArthur and Halsey drives through the Solomons and Papua New Guinea and the Nimitz thrust through the central Pacific – moving into high gear, the Japanese empire was crumbling. Japanese major bases, as those in Truk (now Chuuk) and in Rabaul, were neutralized and its airpower superiority vanquished; with the loss of airpower, its surface ships were doomed in any part of the central Pacific and in vast areas of the south west Pacific.

Their empire shrinking and the battle lines moving closer and closer to Japan, military leaders acted to enhance the defensive capabilities of Guam.

Part of the preparation for the island’s defense was the massive influx of Japanese troops from Asian battle zones, including Manchuria, from where a huge troopship brought more than 5,000 war veterans, fully equipped and ready for Japan’s last stand on Guam. By the time US forces invaded Guam in July 1944 the island was being defended by about 20,000 men.

Part of the strategy for Guam’s defense was to make the island self-supporting through agriculture. The Japanese plan was to accelerate agricultural production so that it could support as many as 30,000 troops for as long as necessary in defense of Japan’s periphery. Brought to Guam were the members of the Kaikontai, a quasi-military group specializing in agriculture; they came with mechanized farm equipment, including about 20 small tractors, a number of plows and cultivators to realize this defensive strategy.

Chamorros used as tools

By early 1944, the Chamorros were mere tools to be utilized without regard to their safety or well-being. Most of the male population were used either at the two operational air strips at Orote and Jalaguac, or at a new one being developed at Ague in the northeastern corner of the island.

Some of the younger males were utilized to help construct pillboxes and man made caves. Still others were used to install real and dummy cannons at several coastal areas, and to transport food and ammunition to key defense outposts. The women were used primarily to plant and harvest farm crops.

At the southern end of the island, the Japanese – in desperation – ordered groups of Chamorro men to lay coconut tree trunks across the road, ostensibly to stop American tanks. In Asan, forced labor constructed a tank trap consisting of trunks buried vertically and arranged in a maze-like pattern. Laborers also piled huge mounts of rocks along the beach, and dug massive holes in the sand in an attempt to block and disable American tanks.

Some local men were directed to hunt and kill all dogs they could find, the rationale being that dogs gave away the presence of people.

In these last days, the Japanese forces were hostile, cruel to the people. Men were beaten at best; at worst, they were executed. Women fared no better and there were numerous rapes reported throughout the island.

Rapes, massacres

While American forces were bombarding the island from off-shore in July in preparation for the eventual invasion, whole-sale massacres were taking place in the island — at Fena, Malesso’, and Yigo.

A group of about 30 young men and women from Hågat and Sumai were packed into a large cave in Fena and massacred. According to John Ulloa, 22, of Sumai, he and six other young men were sleeping in a cave when he and others were awakened by ones coming from a second cave nearby. They were utterly shocked when they discovered that all their friends were murdered.

Six days before American forces hit the beaches of Guam, 46 men and women in Malesso’ were massacred. Two groups of 30 men and women each were forced into two separate caves – Tinta and Faha, now names forever associated with death, tragedy and sadness – located on the outskirts of the southern village. At Tinta, 16 of the first 30 were killed; a rainstorm erupted after soldiers had initially fired into the cave and prevented them from finishing their task. All of the second group perished when they were victims of grenades and those surviving were bayoneted.

When the other Malesso’ residents learned of the massacres, they decided to attack the Japanese. In broad daylight, about 20 Malesso’ men stormed the Japanese quarters, seized whatever weapons they could lay their hands on, and killed every soldier in sight. A hefty Malesso’ man killed a Japanese soldier with his bare hands.

The number of Chamorro deaths in Yigo was never accurately determined but the mutilated bodies of 51 Chamorros were found by American patrols. The beheaded bodies of 30 men were found stacked in a truck near Chaquina, and the bodies of 21 others were found in the jungle near Mount Mataguac.

The besieged Japanese killed virtually everyone in sight during the occupation’s last days. Three teen-agers in the jungle looking for food in Yona were grabbed by soldiers, tied to coconut trees and then beheaded. Many others perished in similar situations.

Another danger late in the occupation was the American bombardment of Guam. Many people, their number unknown were killed, victims of naval or aerial bombing.

Brutality took its toll as the Japanese were becoming more and more desperate with the Americans approaching Guam. Hannah Chance Torres, after having been beaten and berated by Japanese soldiers while she and others were enroute to the Manengon concentration camp, seemed to lose the will to live after the incident. She would later pass away in the night at the camp as relatives sought her husband, Felix. The two had been separated from each other in the hysteria of the forced march to the camp.

There were victims of the intensifying American shelling and bombing of the island as well. Elderly Jose Delgado and two young women were saying the rosary in a makeshift shelter in Agana Heights when a missile blasted the shelter, killing all three people. No one ever knew definitely whether the missile came from Japanese anti-aircraft guns at Jalaguac some three miles away, or from an American plane. Both were trying to destroy each other at the time the elderly man and the two women were killed.

Pascual Artero described Guam as a veritable hell:

So green is vegetation and so pretty a sight had Guam always been, now it was all burned. It had neither a tree nor a coconut with leaves. All now was burned or destroyed by bullets and bombs.

With the coming of the American invasion forces on 21 July, for the Japanese defenders responsible for repelling the Americans, Guam would indeed become a hell on earth.

Editor’s note: A version of this historical account was originally written for the Liberation-Guam Remembers: A Golden Salute for the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of Guam, in 1994.

Omiya Jima, the Great Shrine Island (Guam, in the 1942 Japanese view)

| Ômiyajima | (Ômiyatô) or “the island of the Imperial Court” |

| Population | In early 1942, 22,000 Chamorros (indigenous populace); 14,000 Imperial Army and Navy forces; 483 Americans, were exiled to camps in Japan on 10 January 1942 |

| Capital | Akashi (Red, or Bright, City), formerly Hagåtña or Hagatna |

| Other villages | Asama Mura, formerly Asan; Showa Mura, formerly Hågat; Sumai, now military headquarters. |

| Government | Administered by the Japanese Imperial army and navy as a part of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, the concept being that it will bring together in unity the Asiatic peoples. |

For further reading

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.