A war baby

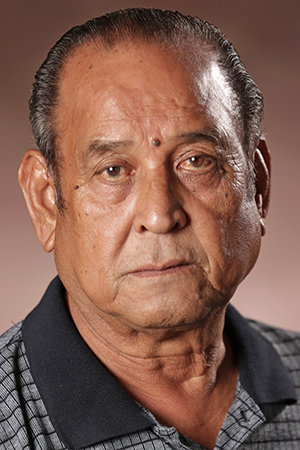

Antonio Adriano Arriola (1944 – ) was born a twin just a few months before the forced march to Manenggon in June. His parents, Antonio Fernandez and Maria Adriano Arriola, carried he and his twin sister, Maria, during the Manenggon march.

I have heard stories that the Japanese would kill the baby if it was crying. So my parents covered me and my twin. I thank the Lord that my twin and I survived.

Arriola’s memories of the war have been created through others.

My mom and dad never liked to tell us about the Japanese, but I just read articles and books about the war. It hurts to learn about the rape and the torturing of CHamoru people by the Japanese, but it is important to know.

Arriola feels a profound need to understand the history and to share it. Arriola’s passion to learn about the occupation on Guam is driven by the heartache his parents and older sister, Trinidad, went through. He father was a forced laborer during the war.

Suffering is a difficult thing to think about, especially if it involves people you know; however, Arriola does not let the discomfort prevent him from knowing the heartaches that took place on Guam. His parents died when he was only 13 years old and he yearns to know about the stories his parents could not tell him.

Reading has brought him to a place where he can get an idea of the different things that happened during the Japanese occupation.

I’ve read an article that Saipanese CHamorus [were] working with the Japanese during the war. It hurts to think about those CHamoru backstabbing other CHamorus.

George Tweed

Arriola enjoys reading about the American holdout George Tweed.

Arriola believes that Tweed represented hope—something the CHamoru people needed during these fearsome times. And while some CHamorus had mixed feeling about Tweed during the war, his admiration of the radioman reveals Arriola’s sincere devotion to the US.

His endless searching and researching for war stories does not compare to his family’s own stories.

My parents lived in Finagayan before the occupation and our family was able to return after the war.

He has many fond memories of his childhood in Finagayan, Dededo in their simple, wooden house. His paternal grandmother lived in Tiyan before the war and sadly was unable to return to her home. She died a few months after the war.

When the military gave the Arriola family back our Tiyan land, my cousin sold it to a corporation.

Arriola believes that the children today would find it harder to cope and to survive than the CHamorus of the war era. He says that life was even harder after the war.

Things are just too modernized. People want expensive things. People back then lived with what they got. There were fine with their wooden and tin home and their jalopy car. Now it’s about the newer, most expensive house or car. Money is evil. It depends on how you use it.

He believes that the young think too much about the wrong things and that reading will give them an idea of how life on our island can be different from the paradise we live in.

If there is something the CHamoru people should take from Arriola’s story, it is to never stop learning about history. Graduating from high school and starting a career should not hinder the CHamoru people from being informed about the stories of Guam.

Learning is a form of survival

We are all still surviving…that’s all that matters now.

Editor’s note: Reprinted and adapted, with permission, from Guam War Survivors Memorial Foundation by Johanna Salinas.