Folktale: Sirena

Table of Contents

Share This

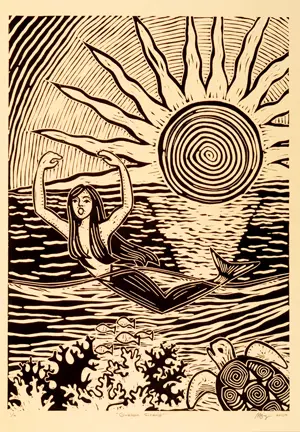

Sirena By Monica Baza

Editor’s note: The following account of the mythological maiden, Sirena, is derived from a manuscript, titled, I Tetehnan. This manuscript is the third part of a series of Chamorro proverbs that were published in 1978 by Anthony J. Ramirez. The titles of the two published manuscripts were Ehemplus Chamorritus and Megaina Munhayan Ki Tetehnan. All three manuscripts contain traditional CHamoru/Chamorro and Spanish loan proverbs.

Guam's mermaid

The mythological maiden, Sirena, in the ‘I Tetehnan’ manuscript is considered a proverb, and not a legend.

Hagåtña tale

A playful young woman named Sirena once lived near the Hagåtña River, right at the place where fresh spring waters dividing the city met the ocean at the river’s mouth. Sirena loved the water, swimming whenever she could steal a moment from her many chores.

One day, Sirena’s nana (mother) sent her to gather coconut shells so she could make coal for the clothes iron. While gathering the shells Sirena couldn’t resist the refreshing river. There she swam for a long time, paying little attention to anything else while her nana called for her impatiently.

Sirena’s matlina (godmother) happened to come by for a visit while Sirena’s nana waited for her daughter to return. Sirena’s nana began complaining about her daughter, becoming angrier the more she spoke. She knew Sirena was probably swimming in the river rather than completing her chores. In irritation, Sirena’s nana angrily cursed her daughter with the words, “Since Sirena loves the water more than anything, she should become a fish!” However, her matlina, realizing the harshness and power of the woman’s words, quickly interjected, “Leave the part of her that belongs to me as human.

Suddenly, Sirena, still swimming in the river, began to feel a change coming over her. To her surprise and dismay, the lower half of her body transformed into the tail of a fish! She had fins like a fish, and her skin was covered with scales! However, from the waist up, she remained a girl. She was transformed into a mermaid!

In her new form, Sirena was unable to leave the water. Her nana soon saw what had happened to her daughter. Regretful of her curse, she tried to take back her harsh words, but she could not undo Sirena’s fate.

So as not be seen or caught by any passerby Sirena gave a final farewell to her mother before she swam out to sea:

Oh Nana, do not worry about me, for I am a mistress of the sea, which I love so much. I would rather be back home with you. I know you were angry when you cursed me, but I wish you had punished me some other way. I would rather you had whipped me with your strap than to be the way I am now. Nana, take a good look at me, for this will be the last time we will see each other.

With these words, Sirena disappeared among the waves. Many stories have been told of sailors who have caught a glimpse of her at sea. According to legend, though, she can only be captured with a net of human hair.

What the story teaches

The story of Sirena occurred in perhaps the most significant and historic site in the Mariana Islands, ‘La Ciudad de Hagåtña.’ The actual account transpired in the Saduk (river) Hagåtña in an area referred to as the Minondu in the Barrio de San Nicolas.

The La Ciudad de Hagåtña (city of Hagåtña) during the Spanish colonial period is unlike what it is today. It was the first city of European heritage in the Pacific, dating its original habitation to the first people that settled in the Mariana Islands some 3,500 years ago. In 1668, upon the arrival of the first Jesuit missionaries to spread the word of Christianity, Hagåtña eventually developed into a colonial city and depicted the structure of the Spanish form of government of Church and State as one.

According to oral history, no one is able to establish the origin of the story of Sirena. It is however one of the most treasured stories in the Chamorro culture, the most retold from generation to generation.

To understand the story of Sirena one must have an historical knowledge of the La Ciudad de Hagåtña during the Spanish colonial era. First is the Barrio systems that were established by the civil and church officials. There were five principal ‘barrios’ in Hagåtña: San Ignacio, San Ramon, San Nicolas, Santa Cruz, and San Antonio. The surrounding barrios were Bilibik, Togai, Hulali, and Garapan.

Each of the barrios differentiated the class system of the Chamorro society. Those who resided in the Barrio de San Ignacio were of the elite class and represented the mixture of Spanish and Chamorro descendants. Barrio San Ignacio was also the first established barrio upon the arrival of the missionaries. Barrio de San Antonio, perhaps was the last barrio to be established, dates its origin as a result of the 1856 smallpox epidemic. Barrio de San Nicolas, the site of where the story of Sirena is related is bordered by the Plaza de Espana, Barrio de San Ignacio, Barrio se San Antonio, the Castillo, Palumat, and a small ‘barrio’ referred to as Santa Rita.

Sirena became half fish and half woman in the Saduk Hagåtña (Hagåtña River) in the area referred to as Minondu. The origin of the river springs forth from the Matan Hanum located in the Sisonyan Hagåtña. The Saduk Hagåtña flowed through the Barrio de San Nicolas and formerly emptied near an area referred to as Paseo de Susana, near the Sagua Hagåtña. In the early 1800s the Saduk Hagåtña was rerouted and eventually flowed through the Barrios de San Ignacio and Santa Cruz and emptied at the Bikana. The significance of these places and the diversion of the Saduk Hagåtña is related to the various versions of the story of Sirena, the etymology of the place names, and the purpose of providing water to the barrios east of San Nicolas.

The story of Sirena is a succinct but tragic account of a Chamorrita maiden who became half woman, half fish as a result of her mother’s curse. The story is a proverb and is founded upon the Chamorro proverb, ‘Pinepetra i Funi’ Saina Kontra i Patgonta’. In literal translation, this relates that the words of a parent carries great weight and influence upon the child. The word ‘pipenpetra’ is derived from the Spanish word ‘petra’ which means stone. Therefore the words of the parent stones the child in their image of himself or herself.

In the original version of Sirena there were only three women involved: Sirena, her mother, and godmother. The significance of these roles represents the matrilineal structure of the ancient Chamorro, and the exclusive right of the mother in the rearing of the child.

The mother represents the temporal obligation of child-rearing. She symbolizes the physical responsibilities of motherhood. Her role depicts the authority she must exercise and execute. The focal nature of her behavior centers her words on Sirena, not directly but indirectly. It was not so much what she said to her daughter but the manner and sentiment of her statement. Both verbally and emotionally she cursed Sirena. Her curse though, manifested in Sirena being affected only physically. Although she regretted her curse, her sincere desire could not be retracted.

The godmother’s character is focused on her single role of spiritual responsibilities. The soul is eternal, which she has moral rights to in the upbringing of Sirena. After the mother cursed Sirena, she demanded her rights given to her at baptism. Whatever is biological is the mother’s right. However what is spiritual is the godmother’s. This right can not be taken from her. The role of the godmother in Chamorro society is highly revered, respected, and influential in the development and growth of the child.

Sirena symbolizes the innocence of youth. Moreover she represents the carefree nature of the Chamorro child-rearing practices. The focal point of Sirena’s role rests upon the abrupt transition from childhood to adolescence. In her case the transition was marked by a single event. Her rite of passage to adulthood occurred at puberty. This is a biological and an emotional transition. All of a sudden her liberties were denied. Her innocence was scrutinized, subjected, and shaded by social restrictions.

Origin of the Sirena story

Evidence indicates that the story of Sirena is not traditional nor original to Chamorro folklore. The word ‘Sirena’ is borrowed from the Spanish language which means a mythological mermaid. Even as early as the Greek and Roman civilizations, there exists the mythological maiden, ‘Sirena’, the goddess of seafarers.

Of particular interest in the Chamorro culture is that the name of Sirena was traditionally not a given name, and girls were not baptized with that name prior to World War II. It was a taboo for Chamorritas. References were implied if one desired to be like Sirena, but no one was ever given that name.

The origin of the story developed from Spanish folklore. Most Spanish speaking countries tell a story in their society with their own original or unique version and adaptation.

The story of Sirena was probably adapted in the Chamorro society by either the missionaries, Spanish government officials, or native mariners in the late 1700s. This introduction is supported by historical evidences of the geological features of the Saduk Hagåtña. The story tells of two sites which were man-made in the 1800s. The first site is the Minondu and the second site is the Bikana.

Oral history relates that the missionaries and Spanish officials had difficulty restricting children from the river which was a water resource. This problem was further magnified when the river was rerouted to span the Barrios de San Ignacio and Santa Cruz. The missionaries and Spanish officials therefore devised this scheme in order to obtain obedience. Not only did they, but the parents also concocted their version. This instilled or built-in fear is pronounced in the early socialization of every Chamorro child, especially among females. Perhaps this explains why most Chamorritas today almost consider the ocean alien and the majority not even knowing how to swim.

In the early 1800 also many young Chamorro men became whalers. Many also were recruited prior to this era during the Manila Galleon Trade. Many of them voyaged to other societies and heard their folklore. Although most did not return, those who did perhaps introduced the story.

Many versions of the story

There are many versions to the story of Sirena. One version relates to men characters. Another version recounts others sites. Still further, Sirena became the ‘Raina del Mar’ (Queen of the Sea). These versions, however, are all later adaptations. The development though of the Chamorro version of Sirena is unique in its account of the three major characters: the mother, the godmother, and Sirena.

To substantiate the original account, the most popular version relates that Sirena was sent on an errand to obtain coconut shells to make charcoal for ironing. At the time that the story occurred, very few people had special clothing which was only a privilege among the elite. Where Sirena came from, the Barrio San Nicolas, near the Minondu, this was almost unheard of. The need for the charcoal was to light the ‘fotgun sanhiyung.’ Early in the morning young children were sent to other houses which often kept a fire burning. Even the possession of firewood was a sign that a family was able to afford a constant fire in their household. Sirena’s household could not even afford that luxury. So every morning she was sent to obtain ‘pinigan’ (ember or charcoal) contained in a ‘ha’iguas‘ (coconut shell).

Minondu, a place name site referred to at the Saduk Hagåtña, is also a Spanish loan word. Minondu is derivative of the word mondo which means clear, pure, and unmixed. The symbolism of water always denotes purity in any culture. It also implies the cleansing off or the soothing off of any individual in religious rituals.

The story of Sirena is perhaps one of the most notable accounts in the Chamorro society because it involves the child-rearing responsibilities of the parents, especially that of the mother. It also involves the obligations of others not biologically related, but essential to the growth of the child, especially on the spiritual level. There is another proverb in Chamorro which places the role and value of the mother’s role, Maulekna un baban nana, ki tai nana. (It’s better to have a bad mother than no mother.)

In the story of Sirena there is another Chamorro saying, Yangin esta unsangan, maputpumanut tati i fino’mu. Hasu maulik antis di pula’ i fino’mu. (Be careful what you ask for. Once you ask for it you can’t take it back.)

By Toni “Malia” Ramirez

Glossary

CHamoru/Chamorro – English meaning

Primet agua di abrit – refers to the first rain showers during the fanumangan (rainy) season. This period is very important to farmers because it marks that period when they should plant their crops.

Masamai – implies softness.

Gef pa’gu – denotes beauty.

Hininguk yan magutus – Refers that it was heard and completed or fulfilled.

‘Yoentrego mi alma’ – Is a Spanish expression which means I commend my spirit.

Lailaina – Means her humming.