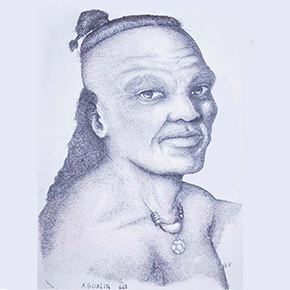

Agualin

Table of Contents

Share This

Cunning and brave leader

Agualin (also referred to in historic documents as “Aguarin”) was a CHamoru/Chamorro chief who led several revolts against the Spanish. He was from Hagåtña, but traveled from village to village to inspire other CHamorus to fight Spanish colonialism and Catholicism.

Accounts of the Spanish-CHamoru wars frequently reference Agualin as a cunning and brave leader, who was able to organize secret meetings in several villages without the Spanish finding out. He knew that the only way to defeat the Spanish was to build an army. The Spanish had guns and soldiers who were trained to kill any CHamorus who resisted their rule and refused to convert to Catholicism.

Although Guam had been a colony of Spain for more than 100 years, it wasn’t until the arrival of Padre Diego Luis de San Vitores in 1668 that CHamorus were forced to change their ways of life. San Vitores had been shocked by the cultural practices of the CHamorus, as many of their beliefs were counter to the teachings of the Catholic Church. For example, CHamorus were not ashamed of their nudity, did not practice abstinence before marriage, and could divorce and remarry if they were not happy in their marriage. He thus started a mission in the island and opened schools and churches to convert the CHamorus.

While some people converted to Catholicism, many others were skeptical of the Church, and did not trust the Spanish priests. Agualin became their leader.

Agualin had witnessed the execution of a CHamoru man who had tried to kill a Spaniard for marrying his daughter. After the man had been killed, Agualin saw a group of CHamoru children who were students at a Catholic school mistreat the man’s corpse. This angered him greatly, as the treatment of a corpse is very sacred in CHamoru culture. He could see firsthand the ways in which the Spanish were killing his people and his culture. Thus, Agualin began rallying villages that were spread out, where the Spanish had not conquered or built churches.

The Spanish called Agualin a trickster, because he was able to deliver eloquent speeches that inspired CHamorus to follow him. After gaining the support of more than 500 people, Agualin secretly planned his first attack. The Spanish wrote that he would rather die than reveal his plans and harm his people.

On 29 August 1676 in the village of Ayran, Agualin and his troops burned a church, the priests’ residence and two seminaries for boys and girls. They worked so quickly that the priests did not have enough time to save their statues and oils in the church, or to warn the island’s Spanish governor. Agualin had hoped the fire would deter the governor and his soldiers, so that he and his troops could attack another village during a church celebration the next day. However, by the time the governor had learned of the fire, everything was in ashes and it was clear the arsonists had long departed. Thus, the governor greeted Agualin and his troops at the celebration of the feast day of St. Rose and the dedication of a new church in the village of Tupungan.

All the fathers of residence and Spanish soldiers were present to celebrate the feast. Agualin called on his followers to come armed with spears, stones and whatever firearms they had taken from the Spanish in earlier battles. When the governor saw Agualin and his supporters at the fiesta, he interrogated them about the fire, but they denied it. Since the governor was present and it was clear the place was surrounded by Spanish soldiers, Agualin decided not to attack on that day.

The burning of the church, however, sparked a revolution. Agualin led many other battles against the Spanish. A large group of CHamorus attacked the Spanish on the feast day of St. Theresa of Jesus on 15 October 1676. They attacked continuously for six months. Every time they attacked they were so numerous that it was impossible for the Spanish to count them.

Following a well-crafted plan by a man named Cheref, seven Spaniards died in a canoe on their way to Hagåtña. Among those killed was Father Sebastian de Mauroy. Agualin is noted to have used this instance to show that there was nothing to fear from the Spanish. Convincing his supporters that the Spanish could be decimated by simply cutting off their supplies while in their base, a date was set to attack the presidio, the Spanish garrison, in Hagåtña in 1677. A crafty plan, however, created by Governor Francisco de Irisarri turned the tide in favor of the Spanish. Following the loss, Agualin and his supporters withdrew to northern Guam and from time to time were spotted participating in hit-and-run attacks.

Although Agualin was able to build large armies, it was nearly impossible for the CHamorus to defeat the Spanish. After the murder of San Vitores in 1672, Spain began to send ships of soldiers and firearms to the island to stifle CHamoru resistance, and capture the leaders of CHamoru revolts. They also made examples of CHamorus who tried to fight them and lost. The Spanish shot two of the men that followed Agualin into battle, and their heads were chopped off and placed on a post to be seen by all.

Agualin finally fell to the Spaniards shortly after the well-equipped and supported Spanish governor Don Jose de Quiroga, an experienced war veteran, arrived in 1679 with the orders to stop the CHamoru resistance to Spanish colonialism. In between battles, Agualin and other warriors would hide out in Rota. Agualin was eventually captured there in August 1680. He was brought to the Spanish garrison in Guam and hanged.

Agualin's speech

In the twelve years since the excessive kindness of those of Agaña admitted the Spanish to our islands, you tell me what advantages we have experienced from their contact with our lands? Are we richer now than before they came? No, because we are as naked now as when they came in. Rather if any of us have acquired some clothes by serving them, that only serves in making us ashamed of the rest of us. Indeed our nudity makes us ashamed now, but when we were all naked, it did not matter. The fruits of our labor are almost the same now, as always, except that they make us work at their expense and they use us in their projects, either for free, or for very little payment.

Why don’t we pay attention to how we have to take revenge against the Spanish soldiers, and beat their firearms? I tell you there are few of them, and there are so many of us that if all the towns came together there will be a thousand of us for every one of them. Why should so many fear so few? With just our stones we can bury them. Besides, isn’t it true that these men live at our expense? The food supplies we give them, isn’t it what we eat? If we simply cut the way so that no one can sell them the fruits that they need to maintain themselves, are other weapons needed to finish them off? It is clear that hunger itself will wear them down and finish them off. So you may stand assured that if you help me, we will be rid of them soon. What is important is for us to keep the secret, not just from them to catch them unaware, but also from all other towns that are friendly with them. Those who are more to be feared are those near the garrison, like Ayran and Tupungan, as they have churches there. However, if they are attacked without warning, they will not be able to resist the power of four or six towns.

This has been the usefulness of them coming here, but the harms done to us continue. Take baptism, for instance, they call it the water of God, but it takes the lives of our children. As for the oil, which they call the Holy unction, it shortens the life of our sick people, so that one rarely survives who receives the unction. They make us go every day to their churches to pray, and if we do not learn their prayers, either they scold us, or punish us. They teach our children their own way, so that they would rather disobey their parents than to [disobey] anything their teachers tell them. A short time ago, these boys dragged [the body of] one of our relatives, because he had not wanted to become a Christian when they killed him; this they did just to please their teachers. These are [supposed to be] the best among the Spaniards, who came to our lands only to teach us the way to Heaven, as they claim, as if all our ancestors had not discovered it, and only they know it, as if they were wiser than ourselves, to know what our ancestors did not know. The result of all this is that, as we can see, we are without freedom, unable to practice the pleasures as our ancestors did; they even want us to impose their own laws regarding marriage, that is has to be with only one woman, and no more, that we have to put up with her until she dies. They want us to spend the holidays in church, and not to work in our properties, and to do other very bothersome things that are enough for us to try and get rid of so much grief, and to finish them off, once and for all.

However, you must not forget something that is even more harmful, the soldiers they have brought along with them. If they stay in this land, it will not be long before it becomes depopulated of natives, whom they kill with their firearms, against which our spears are useless, and much less our stones that do not reach half the distance of their arquebuses. First of all, we are overcome by the havoc that their bullets do to us, before we can even sight them, in order to aim our spears, or wound them with our stones. It is no use either for us to withdraw to the boondocks to seek freedom from them, as they will search for us, and it is sufficient for us to flee for them to consider us enemies and make war on us. It would not be so bad if only they were the ones pursuing us, but our own natives are the ones who made such a rough war on us, either because of the fear they have of them, or for the arrogance imparted by their friendship with them, because we do not submit and obey them as they want, and they might find themselves very offended. What about their taking away of our sons and daughters, with the excuse of wanting to raise them well? What can be more insufferable? Adding to this is the fact that they deprive us of the service of our sons, and our daughters can no longer give us the profit, which is the custom of this country, when the youths want them to live with them, and pay us very well for them. What they do with our sons is use them as servants, and they marry our daughters to the Spanish soldiers, as happened recently in Orote, where the father tried to take vengeance against the Spaniard who had married his daughter; the Governor arrested him and hanged him. That is a good enough reason for us to rise against them for this injustice.

By Victoria-Lola Leon Guerrero, MFA and Nicholas Yamashita Quinata

For further reading

Benavente, Ed LG. I Manmañaina-ta: I Manmaga’låhi yan I Manmå’gas; Geran Chamoru yan Españot (1668-1695). Self-published, 2007.

de Morales, Luis, and Charles Le Gobien. History of the Mariana Islands. Mangilao: University of Guam Press, 2016.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. “From Conversion to Conquest: The Early Spanish Mission in the Marianas.” The Journal of Pacific History 17, no. 3 (1982): 115-37.

Lévesque, Rodrigue. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vols. 1-13. Québec: Lévesque Publications, 1992-1998.

Risco, Alberto, SJ. The Apostle of the Marianas: The Life, Labors, and Martyrdom of Ven. Diego Luis de San Vitores, 1627-1672. Translated by Juan M.H. Ledesma, SJ and edited by Msgr. Oscar L. Calvo. Hagåtña: Diocese of Agana, 1970.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.