Ancient CHamoru/Chamorro Jewelry: Manmade Accessories and Body Coverings

Table of Contents

Share This

Body ornamentation

All human cultures practice some form of body ornamentation. Body ornamentation refers to the ways in which people decorate or dress their bodies for any number of reasons or occasions. This includes the clothing, jewelry, hair accessories, masks, or makeup that people wear, as well as the markings and modifications we make to our skin or other body parts. Although body ornamentation is considered a cultural universal, meaning something found in all social groups, the way we decorate our bodies varies from person to person, as well as within and among different cultures. It may also have different functions or meanings depending on the context in which people decorate themselves.

Different types of body ornamentation can be used to enhance our physical features, such as wearing cosmetics or makeup to make us look attractive, or applying war paint to give a more frightening or aggressive appearance. Body ornamentation can sometimes indicate gender, age or social status, or carry other socially important meanings, especially when used for particular occasions or as part of a special tradition. Body ornamentation is not always simply about covering the body, but a close look can reveal their ideas about fashion trends, beauty or functionality of the items they use to adorn themselves.

In some societies, the body might be permanently modified, for example, with tattoo markings on skin, or by piercing the earlobes, lips or other parts of the body for inserting decorative objects. Most people, however, decorate their bodies temporarily through the clothes they wear, by applying makeup or donning jewelry. Another consideration in discussing body ornamentation is that, like all other aspects of culture, the ways in which people decorate or modify their bodies change over time. These changes often reflect fashion trends based on a society’s changing tastes, preferences or needs.

The ancient CHamorus/Chamorros had different ways of decorating their bodies that were both temporary and permanent. Evidence of jewelry and other body coverings have been found in archeological excavations of CHamoru remains, as well as in descriptions from early Spanish accounts.

A look at dates associated with different decorative items can tell us how CHamoru body ornamentation changed over time. The earliest written descriptions of CHamorus state that these natives wore very little clothing, if anything, at all. But the Spanish did notice items such as jewelry, pendants, belts and hats, especially those worn by elites. However, with the introduction of Catholicism, the CHamorus began to cover their bodies at the urging of the missionaries. Ancient CHamoru practices of designing and wearing ornamental items were largely forgotten.

Today, however, local artists and artisans are reviving some of these ancient practices by designing jewelry and decorative pieces inspired by the past. These pieces include the variety of shell jewelry written about by the Spanish, as well as pieces found in ancient burial sites throughout the island.

Shell ornamentation

Letters primarily from early missionaries in the Mariana Islands in the 16th and 17th centuries describe jewelry made from various seashells and turtle shell. Beads of various shapes have been found, usually perforated through the center of a round section of cone shell or at each end of a cone shape. Rectangular and tubular shaped beads have also been found. Disk-shaped beads, rings, armlets and bracelets were also made, some of which retained elements of the original shell, while others were highly polished.

Comparison of these beads to those manufactured in the Caroline Islands south of the Marianas in historic times indicate that the disks were strung on coconut fiber cord in either uniform sizes, or graded from small to larger beads at the center of a strand. Such strands were also thought to serve as exchange valuables, called ålas.

Spondylus shell became more prevalent during the Latte Period (about AD 800 to AD 1700). Although rare, contemporary artists have reported finding this orange-colored spiny mollusk on Guam beaches, and they do grow in certain bays. Burial excavations dated to the Latte period, around the time of early European contact, indicate that the shell was used as women’s decoration, probably demonstrating high social status and wealth. A particular burial excavated at Ypao beach in Tumon was dubbed by the archeological team as “the Princess of Ypao” because of numerous Spondylus beads located near her cranium (or skull) and her throat, and in strands from the waist. The strands suggest that she wore a fiber belt or apron decorated with the beads. Additionally, she was flanked by two other skeletons, possibly ‘warriors,’ as one had a spear point embedded in his shoulder. The Ypao burial showed that Spondylus disks were paired according to size and shape so that the concave disks faced each other in a string, with graded sizes from smallest at the back, to largest being at the center of the necklace.

Similar beaded belts have been found in other excavations in the Marianas. An early-contact period burial excavated at the Hafa Adai Beach Hotel site in Saipan revealed a female with a belt encircling her lower waist made of large Spondylus disks. The position of the shells indicated that they were probably affixed to a fiber belt. Above this strand encircling her waist was a belt of smaller Spondylus beads.

The Spanish also observed and wrote about these belts. A rare account by early missionary Father Peter Coomans [1673] describes women’s body adornments, which collaborates the findings of archeologists and provides some additional information about the use of Spondylus shell jewelry:

The women have their special feasts, for which they adorn themselves with ornaments on their foreheads, some of flowers like jasmine, and some of valued trinkets and tortoise shells, hung from a string of red shells that are prized among them as are pearls among us, and of which they make also some waistbands with which they gird themselves, hanging around them some small, well-formed coconuts on some string skirts made of tree roots, with which they finish their costume and adornment, and which seems more bird-cage than dress.

The “red shells” described by Father Coomans are Spondylus, although other non-CHamorus have described Spondylus shells as also orange or pink in color.

Another type of ornamentation worn by the CHamorus includes jewelry fashioned from Tridacna, or giant clamshell. In particular, the thick hinge portion of the clamshell, measuring about three to five inches long and an inch thick, has been found in CHamoru burials. It is shaped like a quarter moon (sometimes described as a canoe shape) with holes drilled at each end through which cords could have been attached. Since it was of giant clamshell―which is an extremely dense, strong material and usually reserved for making adzes―it may have been used as an exchange valuable. Written accounts, however, do not describe their use at the time of European contact. One notable example of CHamoru Tridacna shell ornaments was mentioned in the fieldnotes of Hans Hornbostel, an archeologist employed by the Bishop Museum in Honolulu to conduct excavations in the Marianas in the 1920s. His notes from 1924 state that German Governor Georg Fritz in Saipan (1904) found a series of twelve of these objects linked together by a fiber cord, which were taken to a Berlin museum. The Berlin museum collection, however, does not have a record of how or when they were collected.

In addition to Spondylus and Tridacna, turtle shell was also fashioned into CHamoru jewelry. However, a small fragment of turtle shell disk is the only known artifact of this material to have survived to the present. Turtle shell was not only valued as a material for jewelry, but as an item of exchange, such as to ensure peace between warring clans. The value of turtle shell depended upon the way it was obtained. For example, a turtle caught on the beach was not as valuable as a turtle caught in the open ocean under more difficult circumstances. All turtles were first presented to the highest woman of the clan who, in turn, presented it to the chief, who decided the value of the shell and marked it by cutting circular holes in the segments of shell. Smaller holes had different meaning than larger holes, and the number of holes was also significant.

Shell ornaments as exchange valuables

The French Louis de Freycinet scientific expedition that visited Guam in 1819 is the only source which describes CHamoru exchange valuables, particularly Spondylus and turtle shell. They were helped by a very well-educated mestizo (or mixed ancestry) CHamoru named Luis de Torres, who apparently obtained the knowledge from elders of his time. These items could have been used for ceremonial exchanges or as indicators of prestige or wealth. The holes cut from plates of turtle shell (known as lalai) were used to make necklaces by punching a hole in the center and stringing the disks close together to form a cylindrical tube.

This string of turtle shell disks could have also been used as ceremonial belts, as has been documented in the Caroline Islands, south of the Marianas. Indeed, CHamorus may have exchanged these items with their Carolinian counterparts, as prior to the arrival of the Spanish, during the Latte and Early-contact periods, regular trading voyages took place between the Marianas and these islands.

Freycinet also recorded a type of ålas called guinahan famagu’on which was considered priceless. It is described as a string of unpolished turtle shell disks of varying thickness which measured about one inch in diameter at one end and gradually increased to about six inches diameter at the other end. A drawing from the expedition contains an illustration of this guinahan famagu’on. Guinahan famagu’on literally translates as “children’s wealth,” and was given by a family to someone who had rescued or saved their child. The rescuer had the right to accept the gift and thus reestablish reciprocal balance, or refuse it and become an honorary in-law. The latter united both families and accorded the rescuer kinship rights to land and other favors. Therefore, if the rescuer was of higher status than the child’s family, the precious guinahan famagu’on would probably be chosen, while a lower-status person would benefit more by becoming an honorary in-law. One who gave a great gift of knowledge to a child, such as teaching him to be a navigator or makahna (or healer), could also be offered the guinahan famagu’on. It was worn by men on very special occasions, draped around the neck.

Other body coverings

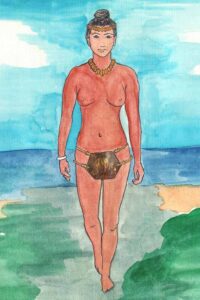

Although early contact documents generally describe the CHamorus as being completely naked, other passages describe instances where some body coverings were observed. Body coverings were primarily for protection from the elements, and included fiber-string skirts and woven hats. Early accounts describe the women’s use of a leaf, called tifi’ (meaning “to pick” or “picked”) to cover their pubic area, held in place by a cord that encircled the waist.

A chamorri (high class) woman also displayed her wealth with Spondylus bead necklaces and by wearing a large plate of turtle shell as a tifi’ apron, tied around her waist by cords attached through holes cut in the top and bottom of the shell.

Father Coomans [1673] described other body coverings on women, such as a skirt that extended from the navel down to the knee. He described these skirts as, “some rather long nerves from leaves.” Additionally, women would adorn themselves with “wreaths with small flowers that look like hyacinths to place on their forehead.” He also observed their use of “a precious-looking collar made of discolored glass beads.”

Guam historian Lawrence Cunningham reminds us that by 1673, CHamorus would have had access to European-made trade beads for over 150 years. Frecyinet’s account mentions the CHamoru sadi, a kind of loincloth, worn occasionally by men. According to his informants, perhaps in ancient times, women wore them, too, although their exact use was not clear. Other items noted by Freycinet include clothing fashioned from tree roots for special feast days. To the Spanish priests, these items “looked more like cages, so gross and wretchedly made were they.” In time of war or while at sea, men would also wear a sleeveless waistcoat or vest, known as gnufa guafak, which was made of woven pandanus leaves.

Both men and women wore hats, although of slightly different shape and style.

Men wore conical hats of plaited leaves to protect them from the sun, especially when fishing. An illustration from the Freycinet expedition shows the use of these hats.

Women’s hats were also conical in shape, but lacked the wide brim seen in men’s hats. Men also fashioned skullcaps from gourds to cover their heads from the sun. To protect their feet, especially while walking over coral, the natives would wear sandals made of woven palm leaves. Otherwise, they would go barefoot.

To provide additional protection from the elements, Frey Antonio de Los Angeles [1596] stated that both men and women applied coconut oil to their bodies to protect them from the cold and wet when it rained. Both fragrant and functional, coconut oil would generate warmth and allow the raindrops to slip off the body.

Did you know?

Agaga’ – It is likely that CHamorus used the word, agaga’, to describe the color of the Spondylus shells, rather than the shell jewelry itself. Agaga’ means “red” in CHamoru, and is used to describe a variety of warm colors. For example, the yolk of an egg is called agaga’, as is the blood red of a hibiscus flower, or the embarrassed blush on one’s face. It is one of the few colors which retain the indigenous CHamoru name rather than adopted Spanish designations―the others being white, apaka’, and black, atilung. (Photo: Judy S. Flores/Guam Museum)

Ålas – Louis de Freycinet wrote that one style of jewelry was generically known as ålas, of which there were two kinds. One sort, known as guini, was worn exclusively by women. The length of the tube and the size of the disks determined the value of this necklace. Usually, the guini was long enough to go around a woman’s neck twice before falling to the navel. Another type of ålas was known as lukau-hugua, which was worn in a sling and dropped to the hip. (Illustration: Guam Public Library System)

Tifi’ – Freycinet’s account described how elite CHamoru women would wear tifi’ made of large plates of turtle shell polished on both sides and tied to the waist like an apron. Women also wore turtle shell plates on their foreheads, or as pendants, interwoven with flowers, while men wore these large plates as breastplate ornaments. (Illustration: Raph Unpingco)

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Driver, Marjorie G. “The Account of a Discalced Friar’s Stay in the Islands of the Ladrones.” Guam Recorder 7, no. 1 (1977): 19-21.

–––. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

Hornbostel, Hans, and Gertrude Hornbostel. Papers, 1924. Microfilm 261.1. Bishop Museum, Honolulu.

Koch, Gerd. Südsee: Führer durch die Ausstellung der Abteilung Südsee. Berlin: Museum für Völkerkunde, 1969.

Lévesque, Rodrigue. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vols. 1-8. Québec: Lévesque Publications, 1992-1996.

Swift, Marilyn. “Hafa Adai Beach Hotel Archaeological Site, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.” Unpublished report, 1999. Swift & Harper Archaeological Research Consortium, Saipan.

Thompson, Laura M. Archaeology of the Mariana Islands. 1932. Reprint, New York: Krause Reprint Co., 1971.