Låncho: Ranch

Table of Contents

Share This

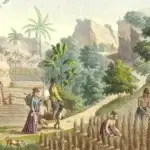

Farming or gathering place

The word “låncho” comes from the word Spanish word “rancheria” and refers to CHamoru/Chamorro farms, ranches, gardens, or family property in the hålomtåno’ (jungle), and even properties along beaches. They can be small or large, and can be active farming ventures with crops and livestock, or can be overgrown jungle in which families harvest wild tinanom, fruta yan gollai siha (plants/crops, fruits and vegetables). Or a låncho can simply be a gathering place for a family or for a clan, a communal piece of property which families can gather.

The term first emerged at the beginning of the 17th century, as a result of Spanish colonization of Chamorros and also as an attempt to resist the demands of their new colonizer. In the centuries since, as Guam has been colonized by two more powers, the United States and Japan, the role of the låncho in Chamorro life as a place of relative calm or safety, or a refuge from the sometimes violent or racist demands of those who come to claim the lands and lives of Chamorros as theirs to determine, continues.

After the Chamorro-Spanish Wars

Following the Chamorro-Spanish Wars (1668-1694), Chamorros found their lives completely altered. Chamorros from the Saipan, Tinian and Gani (northern Marianas) were forcibly relocated to Guam through a policy which was known as reduccíon. This policy was meant to help control the native population, to keep them from revolting against their new masters and new Catholic way of life, and to keep a close watch over them to keep them from reverting to their old pagan ways.

This resettlement radically upset the ancestral land claims which Chamorros previously had. As the Chamorro worldview at the time was deeply rooted in ancestral worship, occupying and using the land of one’s ancestors and living alongside their spirits was one of the most essential parts of life. After the reduccíon, Chamorros suddenly found themselves on other people’s lands, living with other people’s ancestors. Even if Chamorros did maintain their traditional practices in their newly settled villages, they risked retribution from the Spanish missionaries and soldiers who were their neighbors. Furthermore at this period in time the villages were places of disease and death, as Chamorros were crowded together into unsanitary conditions.

The låncho system was created by Chamorros in order to escape the oppressive nature of their new homes. Chamorros sought out pieces of property, sometimes in their original ancestral homes, for this purpose. On these låncho siha, Chamorros were given more freedom in terms of negotiating with the new regime and had more liberties in terms of what they would keep and what they would refuse. For those who wanted to continue with their practices and rituals of ancestral worship, they could do so, shielded from the view of most by the safety of the hålomtåno’.

Spanish period

As time passed Chamorros came to accept Catholicism in their lives and adjust their beliefs and lives accordingly. The låncho as a site for their active resistance to Spanish rule faded away. Chamorros still did not accept Spanish rule over their lives in general, meaning their relationship to the Empire that claimed them was more ambivalent than anything else, but their relationship to it and its institutions in Guam (primarily through the church) stopped being antagonistic, and Chamorros in a sense accepted some of what was forced on them, and simply moved on.

The låncho system helped in the moving on. By still providing a home away from home from the government and the Guma’ Yu’os Katoliko on island, but more so by providing a means of sustenance after their lifestyle had been disrupted by Spanish colonization, the låncho become central to Chamorro life. With their access to the ocean and its bounty limited severely, Chamorros now had to turn to farming and trading with each other in order to survive.

One of the key indicators that Chamorros had moved on, or had found a way to master this transition and make it their own, was the shift in cultural values. Whereas the main source of food for Chamorros had previously been the ocean, and thus Chamorro culture, in particular men’s culture revolved around prowess in fishing, building canoes, navigating, all of this changed with the låncho system. Now Chamorros saw their culture, and their social values as tied to farming, and Chamorros emerged as a people of låncheru siha (those who ranch or employed as farmers). Men who were adept at farming, or had the best machete or fosiños (hoe), or were very generous held great social prestige amongst their family and village. Inversely, fishing became downgraded as an occupation, and although still used as a way of providing food, it was not considered to be an essential activity and those who fished for a living were not thought to be hardworking.

US Naval era

When the colonial guard of Guam changed in 1898, the låncho system didn’t change much. Although the United States proved to be a slightly more involved colonizer than Spain was in the last two centuries of its rule, Chamorro ambivalence to outside rule over their lives didn’t change. The US Navy, which was given complete control over the island and lives of Chamorros from 1898-1941, was marked by some aggressive and some lazy efforts at colonizing and civilizing Chamorros. Different techniques of colonization in the domains of politics, education, health care, economic were all instituted, which were meant to remake Chamorros and their island, to clean them up and to Americanize them, by restricting anything from the plants they chose to have in their yard, to the language spoken by their mouths, to the length of a girl’s skirt. These efforts at acculturating Chamorros were concentrated primarily in Hagåtña and Sumai (Sumay), which were the two most populous villages on Guam and housed the majority of the US military presence at the time.

The låncho system provided some refuge from the watchful colonizing eye of the US Navy, as Chamorros who felt their lives were being invaded or being overtaken could retreat to them for a time. The Navy did operate an Insular Patrol which consisted of a handful of US Marines who would visit the interior of Guam, keeping watch over låncho siha and smaller villages, and giving out tickets to whoever they found in violation of the Navy’s numerous codes and laws.

The propensity that Chamorros had for farming was also something which helped them defend themselves from the colonizing rhetoric of the navy, which maintained that Chamorros were generally lazy and unable to take care of themselves. In resisting this rhetoric and its implications, the farming prowess of Chamorros was often invoked as evidence that Chamorros were a capable people and didn’t need the US in order to survive.

I gera (war)

When the Japanese invaded and occupied Guam beginning in December 1941 at the onset of the American involvement in World War II, the låncho siha of the Chamorros became once again a refuge from a violent and invasive colonizer. In just a matter of days, life on Guam had been almost completely turned upside down. Families fled the island’s main villages to their låncho siha out of fear of falling bombs and the invading Japanese military. The Japanese military was given the rights to evict Chamorros from their homes in order to quarter themselves. Chamorros rightly feared that interacting with the Japanese military presence on island could lead to both overt and subtle violence against themselves and their families. In order to minimize their contact, life on Guam shifted from the larger villages to the låncho siha.

Postwar

Postwar Guam meant even more drastic changes to Chamorro life. Numerous families lost their land to a rapid period of militarization. This militarization meant an infusion of both wage jobs and money into the government of Guam, which helped push Guam away from its pre-war subsistence and bartering economy and towards one based on cash and the importation of goods and food. The changes were all fueled by a desire amongst Chamorros, after the ordeals of being occupied by Japan during World War II, to be American, seeking out whatever way they could to Americanize themselves, whether it be by buying cars or giving up the Chamorro language. This meant that the farming lifestyle which had been at the center of Chamorro lives for two centuries, started to disappear and take a lesser role in how Chamorros perceived themselves or provided for themselves.

The låncho is still a part of Chamorro life as a site for farming and providing food. The låncho for Chamorros can provide a resting place for those seeking to take a break from modern Guam and be reminded of an earlier time. To those families who possess properties which they refer to as lancho, or ranch, as they are often referred to today, it can be conceived of as more of a familial plot of land, at which people can collect plants or fruits from the hålomtano’, raise a few pigs for an upcoming family event, or as a gathering place for families.

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

Hattori, Anne Perez. Colonial Dis-ease: U.S. Navy Health Policies and the Chamorros of Guam, 1898-1941. Pacific Islands Monograph Series 19. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004.

Russell, Scott. Tiempon I Manmofo’na: Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1998.

Souder-Jaffery, Laura Marie Torres. Daughters of the Island: Contemporary Women Organizers of Guam. MARC Monograph Series 1. Mangilao: Micronesian Areas Research Center, University of Guam, 1987.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.