Guma' Uritao

Table of Contents

Share This

Ancient CHamoru/Chamorro bachelor houses

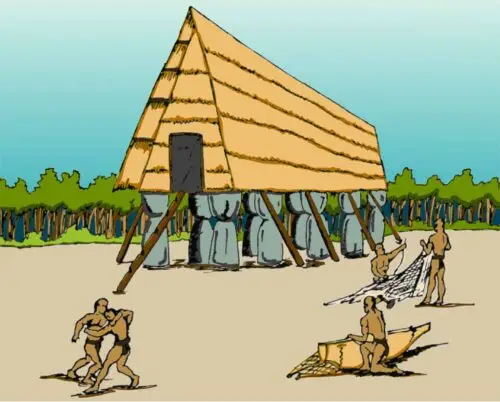

I mangguma’ uritao, men’s houses, were houses for young CHamoru/Chamorro men in the Mariana Islands from ancient times until the late 1600s (‘I’ means ‘the’; ‘man’ makes the term plural). CHamoru youth were expected to model and actively learn the skills of being men and women from their elders. While girls gained much of this knowledge through performing activities with their female relations, CHamoru mothers sent their sons to i guma’ uritao of her family.

There the young men would live and learn from his mother’s male relatives how to fish, hunt, navigate, chant, build canoes and houses, paddle, perform in combat, make tools such as spearheads, slingstones, adzes and files, and more. They would also observe and learn the social and cultural behavior expected of CHamoru men from the older married men who served as their mentors. They also learned about sex from the ma’uritao, the young women who lived in the i mangguma’ uritao specifically for that purpose.

Latte, stone house posts for which CHamorus are well known, became part of CHamoru culture around BP 1,000 though wooden house posts may have existed before then. Not all CHamoru houses were then built on latte, but i guma’ uritao were. Indeed, they were likely the largest latte house of each village.

I mangguma’ uritao also acted as social halls for men and served as a place for community events. In these structures, CHamoru young men and women learned about the opposite sex. This tradition held even greater significance inasmuch as ancient CHamorus married outside their clan. Since CHamoru villages were made up of clan members, sending young CHamoru women to i mangguma’ uritao of a different village provided an opportunity for young men and young women, not closely related to each other, to meet and develop intimate relationships. Young women and men were considered to be more mature, equipped for adulthood, and ready for committed relationships as a consequence of their experiences at i mangguma’ uritao.

The neighboring Micronesian islands of Yap and Palau had similar cultural systems in place for their younger society members. Much attention has been focused on this latter function of i mangguma’ uritao, which has deemphasized the way that i mangguma’ uritao fit into and served the entire CHamoru socio-politico-cultural system. I mangguma’ uritao provided for continuance of vital skills and knowledge—ensuring generations of men skilled enough to protect village, learn skills and maintain histories and traditions.

I guma’ uritao were despised by the Spanish missionaries who settled in the Mariana Islands in 1668. Missionaries preached outside i mangguma’ uritao and burned them down in an effort to end what they viewed as the ‘sinful practices’ of premarital sex that occurred inside. Eventually, these houses died out as a result of the forceful and successful implementation of the sacrament of marriage during the 17th century. Because i mangguma’ uritao housed much more than that, CHamoru society was forever altered with the loss of this convention.

By Kelly G. Marsh-Taitano and Brian Muna

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Herman, RDK. “Guam: Inarajan – Native Place: Village.” Pacific Worlds, 2003.

Hestorian Taotao Tano’: History of the Chamorro People. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1993.

Iyechad, Lilli Perez. “Death: The Expression of Grief.” In An Historical Perspective of Helping Practices Associated with Birth, Marriage and Death Among Chamorros in Guam. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2001.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.

Russell, Scott. Tiempon I Manmofo’na: Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1998.