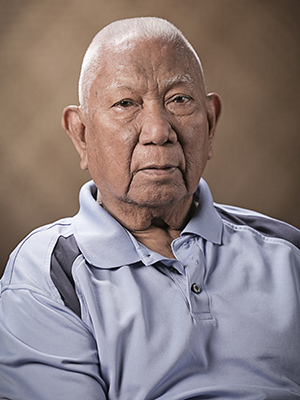

War Survivor: Jesus Camacho Babauta

Survived by his wits

When the Japanese invaded Guam in 1941 Jesus Camacho Babauta (1928 – 2023), from Sumai, was just shy of 13 years old. Life in Sumai had always been peaceful for young Babauta. There was an abundance of lemmai (breadfruit), mango, papaya, banana, and other fruit trees as well as vegetables grown at the låncho (ranch). They fished and hunted for their food. He was born 23 December 1928 and lived with his parents, Antonio Rivera Babauta and Maria Taitano Camacho, and his six siblings.

Babauta remembered the shiny planes that flew low over the school during the flag ceremony.

I didn’t know anything about Japan at that time. We could see the pilot and even waved at him.

Jesus Camacho Babauta

Then there was a loud explosion. All the kids thought it was a tanker that blew up. Another explosion sounded. Finally, he heard from a friend whose father worked at the cable station that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor and that they were at war. It was then he learned that the Japanese had bombed Standard Oil, the Pan American hotel, and the Marine barracks, all at Sumai.

I remember thinking, okay, they are at war, but why are they bombing us? We are not at war.

One of his most painful memories was having to help tear down his beloved Sumai home. The Japanese had ordered residents to tear down their homes or they would be burned down. Babauta described how the home was well-crafted and built without nails. The family scrounged for whatever lumber and material they could salvage to take to their låncho in Apla, where they would live for the duration of the war.

We were never allowed to go back to Sumai. Sumai was gone.

The boys were assigned to work on making an airfield. Babauta said he was the wheelbarrow boy. They were not paid or given food and water. Although he did not recall being abused, he witnessed the Japanese beat up and even kill others. Under the constant fear of the Japanese, especially the commander with the big sword, the people worked hard all day long just to survive.

No one was allowed at the beach to fish or else the Japanese would accuse them of being spies, so they had to sneak to get sea water to make salt. Fish they could do without, but salt was a necessity. His parents made salt to barter with other families.

Eventually, they were marched up to Manenggon. It was at Manenggon that Babauta was most affected during the war.

How could the Japanese do that to the people? They brought all the CHamoru(s) there. We were forced to share a shack with three other families. There was no space. No running water. No food. The Japanese refused to let us do anything but wait there and we were not allowed to leave.

There was a river flowing nearby at Manenggon, but with no place else to use the toilet, the surrounding area quickly became a cesspool of excrement, which was foul-smelling and intolerable.

Taken from Manenggon to Fena

Babauta and his cousin, Tommy Camacho, were among a group of CHamorus, who were taken from Manenggon to Fena. Babauta had overheard the Japanese talk about getting everyone drunk with saki and then killing them. Cold, tired and hungry, Babauta shared what he had overheard with Tommy. Babauta and Camacho decided that they were going to sneak out and escape from Fena that night. Babauta asked the Japanese guard if he could go relieve himself. When he was excused, he went and hid and waited for Tommy. The two escaped and made their way back to Manenggon to be with their family. Two days later, a wounded survivor arrived at Manenggon and told Babauta that everyone but two others were killed at Fena.

Once again at Manenggon, Babauta and Camacho were among a group of CHamorus taken by a team of Japanese, this time, headed for Yigo. Since they left Manenggon at dusk and it got dark quickly, they stopped in Yona for the night. Babauta noted the wounded and crippled Japanese soldiers inside the church.

After the morning ritual of bowing to the Emperor, they continued walking down the road, leaving Yona just before dawn. At the bottom of the hill at the Ylig Bridge, the party left the road and detoured into the jungle. Soon they heard the others at the front of the pack hollering “hayaku” (hurry) for them to go faster. Realizing that the group had spread out so much that they were probably lost, Babauta and Camacho slowed down so that when their Japanese guard hurried ahead to catch up with the rest of the group, the cousins quickly left the pack and turned back towards Manenggon.

They found refuge on a hill where they rested and found a papaya and a coconut. They didn’t have any tools so they just used their hands to clean out the seeds of the papaya and used a rock to hit the coconut until the husk got soft enough to peel. Keeping the ocean to their left, they inched forward on their hands and knees, continuing up the hill.

Who goes there? CHamoru!

Then they heard someone shout, “Who goes there?” Tommy quickly answered, “CHamoru!” They were told to come closer to be recognized.

The American solider wanted to know where all the CHamorus were and if there was a mayor or someone in charge of them. Then he asked the boys if they were hungry. When they said yes, they were offered C-rations.

When I opened the C-rations, there was spaghetti, cookies…todo klasi (everything)…hamburger, kesu (cheese)!

After they ate, Babauta and Camacho led the four American soldiers down to Manenggon to find the commissioner.

When they arrived at Manenggon the following morning, Tommy told the commissioner that the Americans were there to rescue them. The commissioner was fearful saying that he could not go because the Japanese guard would kill him.

CHamorus are freed

The American soldiers who were trailing behind Babauta soon caught up with them. The American leader told the commissioner that he had shot and killed one Japanese guard and chased after another who was at the other end of the camp and shot him dead, too. Near the body of that second Japanese guard was a CHamoru woman whom the guard had just killed. When the American went back to the first Japanese he killed, he discovered a case of hand grenades which he suspected was going to be used to kill the CHamoru people.

Up until that point, Babauta said he didn’t believe that the Japanese had intended to kill them at Manenggon. But when those grenades were found, he believed that if the Americans hadn’t come to Manenggon when they did, the people there would be dead. This realization was ingrained in his memory as he watched four American trucks evacuate the CHamorus from Manenggon.

Jesus Camacho Babauta passed away on 19 January 2023.

Editor’s note: Reprinted and adapted, with permission, from Guam War Survivor Memorial Foundation by Christine Dimla Lizama.