Elena Cruz Benavente

Traditional weaver

Although weaving was once a practice in which nearly all CHamorus participated, a select few have been singled out over the past few decades due to their exemplary skill and commitment to perpetuation of the craft.

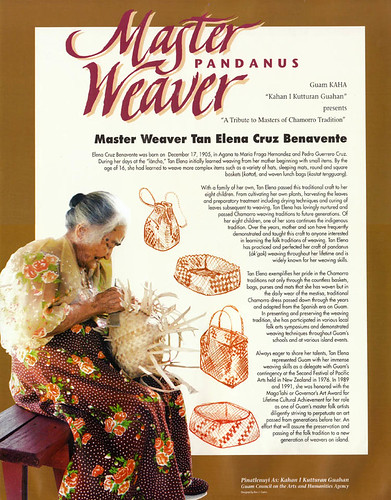

Elena Cruz Benavente (1905 – 2005) was a master folk artist, recognized for her skill in weaving natural materials such as coconut palm and pandanus leaves.

Born in Hagåtña on 17 December 1905 to Maria Fraga Hernandez and Pedro Guerrero Cruz, Benavente learned how to weave coconut and pandanus (ük’gak) leaves as a child, as many island residents did. By the age of 16, she had learned to weave more complex items, such as sleeping mats (guaffak), round and square baskets (kottot), and lunch bags (kostat tengguang).

Weaving is an important cultural practice in many Pacific societies and CHamorus were known as being particularly skilled. Many utilitarian items, such as food baskets and traps, mats for sleeping and ceremonial use, and thatching for houses, were produced by hand. Weaving was also important to the cultivation of community life. In a time before contractors built houses, villagers made their own homes. This meant that they had to work together during the dry season to fix or make new thatch roofs. A typical 18 to 20 foot-long roof could use up to 1,000 coconut leaves and take up to a month for a village to craft. Many people were needed—not just to weave, but also to climb trees, trim leaves, and prepare materials for assembly. Thus, a thatching party, like other community activities such as fiesta preparation and church celebrations, was one component of CHamoru life that not only produced goods, but whose very practice exemplified and transmitted CHamoru values like inafa’maolek and chenchule’.

Thatching roofs were an entry point to the weaving practice. Typically, once a person could reliably weave thatch, that person had enough experience to move on to basket craft, and later, pandanus weaving. In other words, making thatch roofs was a beginner’s way of becoming a weaver. Making a thatch roof required that the elders taught and mentored younger community members how to weave.

The changes in CHamoru society following World War II, however, would affect weaving traditions, both in functionality and perpetuation. In the four to five years immediately after World War II, people rebuilt their houses using wood and thatched coconut leaves. But with the importation of manufactured materials and military surplus like concrete and tin in the 1950s, house building—and the accompanying community traditions like thatching parties—changed. One reason for gathering together—making a thatch roof—was no longer essential to how people made their homes. The decline of these thatching parties also meant that weaving skills declined. With the demand for that basic skill decreasing, peoples’ weaving skills also weakened.

But while others gave up the practice due to changing times leaving less demand for weaving skills, Benavente kept up the practice and eventually passed it on to the next generation. She married Jose Quichocho Benavente from Dededo and together they had eight children, Elisa, Jose, Jesus, John, Priscilla, Elena, Manuel and Pedro. Throughout this period of change into the modern world, Benavente continued her weaving amidst (or perhaps because of) the demands of raising eight children, supporting her husband, and caring for a house. Ever the CHamoru traditionalist from her dress (a mestisa) to familial duties, her weaving did not stray from the forms and materials she had known since she was a little girl.

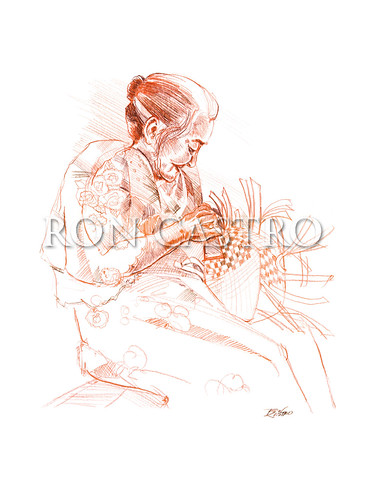

Benavente passed this traditional craft to those of her children who wanted to learn. Remarkably, she cultivated her own plants, harvested the leaves and used traditional drying and storing techniques to prepare the leaves before weaving. Benavente practiced and had perfected her craft of pandanus weaving as well as coconut leaf plaiting throughout her lifetime and was renowned for her skills in creating art from these traditionally utilitarian objects.

Her method of teaching others her craft was also faithful to pre-World War II traditions. While formalized, Americanized schooling emphasized strict adherence to schedules, lectures, and mandatory attendance, Benavente would accept students at their request and at mutually agreeable times. Students would first observe her, attempt to weave on their own, and ask the all important question of “taimanu?” (how?) when needing help. A student would progress from making fans, to thatched roofs, on to baskets, and, if interested, on to the demanding, labor-intensive craft of pandanus mat weaving. There was no money exchanged for teaching, although bartering or sharing things—again, in the tradition of chenchule’—was acceptable.

Beginning in the late 1960s when her son, John Benavente, returned to Guam from the United States, the two found more of a demand for their skills, although it would not grow to the pre-war demand in her lifetime. A resurgent interest in CHamoru-specific traditions and bilingual education, embedded in larger social forces of political change, took hold in the local community, facilitated by the beginning of cultural fairs, such as those held at Jeff’s Pirate Cove in Ipan. Meant initially to promote the business, over time these fairs helped shape a market for CHamoru cultural products as well.

Because of her abilities, Benavente was selected to represent Guam at the Second Festival of Pacific Arts held in New Zealand in 1976. She was honored with the Maga’lahi or Governor’s Art Award for Lifetime Cultural Achievement for her role as one of Guam’s master folk artists in 1989 and 1991.

Traditional weaving evolved from a skill of necessity to an art form, over the course of Benavente’s 99 years of life on Guam. She died a few months shy of her 100th birthday, in 2005, leaving a legacy of dozens of weavers, including her grandson Mark Benavente, and a greater appreciation among the Guam community for her talent, generosity, and her contributions to the preservation of CHamoru culture.

For further reading

“Elena Cruz Benavente.” In I Manfåyi: Who’s Who in Chamorro History. Vol. 2. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education and Coordinating Commission, 1997.