The Journey of SMS Cormoran II

Table of Contents

Share This

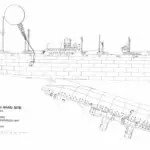

The German cruiser Cormoran II, intentionally scuttled by its own captain during World War I, sits on the bottom of Guam’s Apra Harbor. The shipwreck, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975, would be noteworthy by itself, yet the sinking of the Japanese ship Tokai Maru nearly on top of it during World War II makes it one of the world’s most unique dive sites. The story of the ship, its long sojourn in Guam, its sinking, and its crew as prisoners of the United States is one of those fascinating but forgotten tales from history.

Germany in Asia and the Pacific (early 20th Century)

German expansion in the Pacific occurred at a later date than that of other countries, yet in China they were able to secure a leasehold of 99 years for what they referred to as Kiautschou Bay with the town of Tsingtau (also referred to as Tsingtao) as its administrative center. Today, this area is known as Qingdao on the Shandong Peninsula. Although taken originally by force by the German Navy, a negotiated settlement between Germany and China led to the concession agreement. Other countries soon secured concessions for ports along the Chinese coast as well, with Japan settling in at Port Arthur after seizing it from Russia, Great Britain at Weihaiwei, and France at Kwang-Chou-Wan.

Germany spent lavishly to make a proper colonial town out of Tsingtau. The colony was designed to show other countries how they should do “proper colonization.” Broad avenues were laid out, solid European style buildings were constructed, electricity and fresh water were available in each structure, and the entire area was controlled and administered by German laws. This was the home port of the Kaiserliche Marine’s, or the Imperial German Navy’s, Kreuzergeschwader or Ostasiengeschwader, or the German East Asia Squadron.

The German East Asia Squadron was a collection of cruisers and Germany’s only overseas squadron not supported directly by German seaports. As the Ostasiengeschwader was six thousand miles from home, Tsingtau’s great naval base was built to handle all necessities of the fleet. Shore fortifications were strongly built and the harbor was easily defended against raiders, yet without immediate assistance, it was believed that Tsingtau might fall in the event of a determined and well supported attack. The cruisers were important to Germany as her holdings throughout the Pacific warranted a strong naval presence, and they allowed German vessels engaged in trade in Asia to be shadowed by military ships.

As the world edged closer to war during the summer of 1914, the German flag flew over the Mariana Islands (except Guam), the Caroline Islands (present day Federated States of Micronesia and Palau), the Marshall Islands, and the Solomon Island chains. Germany also held large land holdings in the Bismarck Archipelago and their ships made frequent voyages throughout the islands, down to Australia, and up to China. One of the vessels that frequently steamed the Pacific on patrol missions was the Seiner Majestät Schiff (or SMS, translated from German as, “His Majesty’s Ship”) Cormoran, a sloop of 1,614 tons with “eight 4.1 in. guns and seven smaller quick-firers.” An Australian newspaper later quipped that the Cormoran had a speed “given as 16 knots, but it is very questionable whether she often attained it.”

The vessel, built in 1892, visited more than 40 ports, including several visits to Guam, steaming the Pacific during her long career; she was at Tsingtau when Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife were assassinated in Sarajevo in June 1914. When Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August 1914, the SMS Cormoran was still there undergoing repairs alongside “four gunboats, one destroyer, and the protected cruiser Kaiserin Elisabeth, the only Austro-Hungarian warship stationed outside European waters.” Forewarned of possible war, Vice Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee, commander of the East Asia Squadron, had ordered his vessels to meet at Pagan in the Mariana Island chain at the outbreak of war.

The SMS Cormoran I and the SMS Cormoran II

The light cruiser SMS Emden had put to sea immediately to head toward the rendezvous with Spee while SMS Cormoran stayed back unable to steam. The Fregattenkapitän (German: Frigate Captain) Karl von Müller of the SMS Emden passed south of the Korean Peninsula looking for Russian ships in the busy sea lane of the Tsuchima Straits. On the evening of 4 August, Müller spotted a vessel that immediately turned away from him and ran for Japanese territorial waters. Emden fired 12 warning shots across the ship’s bow and finally got it to come to a stop. SMS Emden’s boarding party soon ascertained that the vessel was the SS Rjäsan, a 3,500-ton Russian Volunteer Fleet passenger and freight steamer built by the Schichau-Werke shipyard in Elbing, Germany (now Elbląg in northern Poland). There were about eighty passengers aboard transiting from Nagasaki to Vladivostok. Müller decided rather quickly to seize the ship for his country.

As the vessel was capable of good speed, fairly new, and now, the first German prize of the war, Müller chose to return immediately to Tsingtao to have engineers convert the ship into an auxiliary cruiser to assist in the war effort. This was agreeable to Korvettenkapitän (German: Captain) Adalbert Zuckschwerdt who had commanded the aging SMS Cormoran for nearly a year, and now, the engine of the Cormoran was damaged beyond repair. Zuckschwerdt gained command of its worthy replacement. It was decided that the SMS Cormoran would be stripped down and the newly flagged Rjäsan would receive the guns, crew, and name of the smaller ship; she was ready to sail in less than a week.

The crew of the newly ordained SMS Cormoran II was augmented by sailors from other ships in port, volunteers, and reservists. Herb Ward, in his excellent study of the ship, described the crew’s numbers: “there were 16 officers, 8 petty officers, and 218 enlisted men, as well as 28 New Guinea men (formerly of the “Old Cormoran”), and four Chinese laundrymen.” SMS Cormoran II left Tsingtao on 10 August and joined Spee’s cruiser squadron 17 days later. The original Cormoran was soon scuttled in Kiautschou Bay to keep it out of enemy hands when Tsingtao was attacked and seized shortly after by Japan.

Evasive maneuvers and arrival in Guam

SMS Cormoran II began her last fateful voyage through the Pacific Ocean by escaping eastwards for the rendezvous with Vice Admiral Spee and the rest of the German East Asia Squadron in Majuro’s lagoon in the Marshall Islands. Spee ordered the new addition to his fleet to detach with SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich upon a mission of harassment of German enemies in the waters of the Pacific and the South China Sea.

Captain Zuckschwerdt was able to gather stranded Germans from various stations, and avoid British, French, and Japanese warships. Yet without finding coal, the Cormoran was forced to play defense instead of attacking as they desired. On the north coast of New Guinea at modern day Madang, then a German colonial town known as Friedrich Wilhelmshafen, they took aboard the German acting Vice Governor Dr. Karl von Gebhard. They also evaded four British warships, and then steamed to Yap to obtain additional troops (from the SMS Planet) which had to scuttle their vessel, before returning in an attempt to seize the town by force. Captain Zuckschwerdt decided an attack would be suicide as Australian troops had erected a wireless station in his absence. He returned to Yap only to find it covered by the Japanese battleship Satsuma. After two months of crisscrossing the Pacific, Zuckschwerdt decided to hide the ship in Lamotrek Atoll, 350 miles east of the main island of Yap, so he could send emissaries to Guam. In a cutter purchased at Lamotrek, a small crew was sent to seek a neutral harbor, coal, and more information from Germany. The captain waited two more months at Lamotrek, then decided to run for Apra Harbor, Guam.

The Cormoran successfully entered the bay unseen by patrolling Japanese ships on 14 December 1919. However, requests for coal to continue evading her enemies was denied, and the Cormoran was interned by order of the United States Naval Captain William Maxwell, Governor of Guam. While interned ships normally have their crews removed along with their armaments, provisions, and communications equipment, Guam did not have any place ashore to locate 373 men (who actually outnumbered the American garrison), so they were allowed to stay aboard the ship.

Interment and the scuttling of SMS Cormoran II

SMS Cormoran II settled in for a lengthy stay while Japanese warships patrolled the waters of Micronesia and the war grew in intensity in Europe. Her fight in the war was over, yet the fighting between Captain Zuckschwerdt and Governor Maxwell was just beginning. The two spent the next sixteen months at each other’s throats as they each appealed to their governments abroad for support of their non-compromising positions. Josephus Daniels, then Secretary of the Navy, went so far as to inform the German Ambassador Count JH von Bernstorff that,

…the Navy Department has received, for many months, reports of incidents that have induced the conclusion that greater comfort and contentment of the German interned personnel would perhaps follow the exercise of greater tact on the part of the commanding officer of the Cormoran and some of his officers in their intercourse with the authorities of the island.

The amount of message traffic found in archived State Department records concerning the SMS Cormoran II is astounding. The pressure on the Departments of Navy, War, and State in the United States was only a fraction of that which the local island commander, Governor Maxwell, was experiencing as Zuckschwerdt used every opportunity to take a strong, semi-belligerent position with a man he disdained as a poor leader and officer.

Governor Maxwell was eventually involuntarily relieved in April 1916 after having a mental breakdown. That same month the German government had made repeated attempts to have the ship moved to San Francisco, California. However, the Departments of both Navy and State had firmly rejected the idea. Japanese newspapers started to write that the United States was going to move the ship in convoy. This prompted the Japanese government to tell the US embassy in Japan that, “as it might be claimed that when it returned to the high seas it immediately became liable to attack and capture.” There was also the matter of Russia claiming that their ship, the Rjäsan had been seized in Japanese neutral seas (Japan had not yet declared war on Germany at the time of the Rjäsan seizure). The removal of Governor Maxwell, though, seemed to have calmed matters.

After a couple of acting governors served, Captain Roy C. Smith took charge of Guam at the end of May 1916 and relations with the Cormoran improved rapidly. Though still interned, her crew enjoyed more freedom, and were even allowed to leave the ship and come ashore within an area extending from Tumon to Piti. Social interactions with people on the island became more amicable and commonplace. There was even a New Year’s Day wedding between Dr. Gebhard (picked up by Cormoran in her run to New Guinea) and Eleanor Blain, a US Navy nurse, to kick off 1917. If their honeymoon lasted a month, it ended just as the United States was severing diplomatic relations with Germany in February 1917.

San Francisco papers reported that Marines at Guam had prevented the crew of the Cormoran from disabling the ship by boarding the vessel when they heard strange sounds while passing in their small boat. Further inspections in February 1917 (ostensibly to check Cormoran coal levels) were ordered by Governor Smith. These inspections were initially rejected by Zuckschwerdt so his men could dismantle the device he had already implanted to destroy the ship in the case of war. The inspection found nothing out of the ordinary and the coal levels were the same as they had been all along, yet tensions were now extremely high.

Far away from the placid waters for Apra Harbor, the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic and an intercepted request for Mexico to join Germany led to a 6 April 1917 declaration of war from the United States. Zuckschwerdt had immediately put his plan back into action when the American inspection team left his vessel in February 1917. He ordered the dismantled explosive charges made from coal dust and gasoline to be reassembled and placed into the forward coal bunkers. The main condenser sea suction valve was rigged to allow water in at a moment’s notice, and the charges were wired so that they may be detonated by a remote switch in the captain’s cabin. His preparations made, Zuckschwerdt awaited news of what would be the fate of his ship.

Governor Smith received the coded message “W…A…R” from Washington and immediately put into motion a previously designed plan to seize the SMS Cormoran II as a prize of war. Orders went out to Marines manning guns around the island, including the big guns on Mount Tenjo and those nearest the ship on Cabras Island. He dispatched Navy and Marine Corps personnel in his motor launch to go take the ship. Dr. Gebhard was heading toward shore from the Cormoran (to see his wife ashore) and immediately turned around. As author Dick Camp states:

Lieutenant Hall ordered a Marine to fire across the bow with his rifle as a signal to heave to. ‘The shot, as I recall was fired by Cpl. Michael B. Chockie,’ Hall recalled, ‘the non-commissioned officer in charge.’ This simple act allowed the Marines to lay claim to having fired the first shot of war.

After boarding the ship, Lieutenant Owen Bartlett presented the governor’s demand for Zuckschwerdt to turn over his officers, crew, and ship. Zuckschwerdt told Bartlett to relay to the governor that he could have the men but not the ship. As soon as Bartlett left his vessel to relay the message, Zuckschwerdt put his plan into action. Men mustered on the fantail and began jumping into the water as the charges were detonated near the starboard bow. Swimming away from their sinking ship, they were soon picked up by every small boat that could get underway in the harbor. Purportedly, Zuckschwerdt was told of his bravery in blowing up his ship when he was pulled from the water; he would later relate this tale to others. In the end, the ship would sink almost immediately and seven of the crew either died of heart attack or drowning.

For further reading

Ancestry.com. “New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957.” Immigration & Travel, 2010.

–––. “California, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959.” Immigration & Travel, 2008.

Auckland Star. “The Sinking of the Cormoran.” 10 October 1914.

Baker, Newton D. Newton D. Baker, US Secretary of War, to Robert Lansing, US Secretary of State, 16 June 1918. “The Secretary of War (Baker) to the Secretary of State.” Foreign Relations, 1918, Supplement 2. I: Prisoners of War. Edited by Joseph V. Fuller. Pages 3-4. File No. 763.72114/2738. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1933.

Ballendorf, Dirk A. “The hot Not Heard Round the World: S.M.S. Cormoran and the German/American Confrontation at Guam During World War I.” Select paper from the 59th Annual Meeting of the Society for Military History, Command and Staff College of the Marine Corps University, Quantico, VA, 1992.

Boland, Micajah. A History of the War Activities of the USS Pocahontas. New York: Press of Joseph D. McGuire, 1919.

Camp, Dick. The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood: US Marines in World War I. Minneapolis: Zenith Press.

Daniels, Josephus. “Letter to Count J.H. von Bernstorff.” Correspondence from Secretary of the Navy to German Ambassador. 17 February 1916. Washington: Office of the United States Secretary of the Navy.

Giordani, Paolo. The German Colonial Empire: Its Beginning and Ending. Translated by Gustavus W. Hamilton. London: G. Bell and Sons, 1916.

Honolulu-Star Bulletin. “Cormoran’s Captain Threatened with Lynching by German Crew.” 4 June 1917.

Kingsport Times. “Germans Once Held at Atlanta Now Prospering on Farm There.” 13 October 1929.

Lochner, RK. The Last Gentleman-of-War: The Raider Exploits of the Cruiser Emden. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2002.

Moore, John Hammond. The Faustball Tunnel: German POWs in America and Their Great Escape. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2006.

Nagler, Joerg A. “Enemy Aliens and Internment in World War I: Alvo von Alvensleben in Fort Douglas, Utah, a Case Study.” Utah Historical Quarterly 58, no.4 (1990):388-405.

New York Times. “1,300 Germans Going Home: Interned Sailors on Way Here with Nine Cars of Souvenirs.” 24 September 1919.

Polk, Frank L. Frank L. Polk, Acting US Secretary of State, to Hugh R. Wilson, US Secretary of Legation in Switzerland, 4 March 1918. “The Acting Secretary of State to the Chargé in Switzerland (Wilson).” Telegram. Foreign Relations, 1918, Supplement 2. I: Prisoners of War. Edited by Joseph V. Fuller. Pages 24-25. File No. 763.72114/3331. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1933.

Powell, Allan Kent. 1984. “The German-Speaking Immigrant Experience in Utah.” Utah Historical Quarterly 52, no. 4 (1984): 304-346.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.

San Francisco Chronicle. “Crew of Cormoran To Be Imprisoned.” 9 June 1917.

–––. “Governor Orders Compulsory Military Training in Guam.” 25 March 1917.

Shipler, Harry. “Fort Douglas, German Prisoners.” Photograph. Utah State Historical Society, 27 August 1917.

Shipler, Harry. “Fort Douglas, German Prisoners.” Photo number: Shipler #18161. Utah State Historical Society, 27 August 1917.

Sondhaus, Lawrence. World War One: The Global Revolution. Google eBook. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Spennemann, Dirk HR, ed. “Marshall Islands History Sources No. 30: Itinerary of the German cruiser S.M.S. Cormoran, 1902-1914.” Digital Micronesia–Marshall Islands–An Electronic Library and Archive, last modified 9 October 2005.

Taylor, John M. “Karl Friedrich Max von Muller: Captain of the Emden During World War I.” MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, 2007.

Ward, Herbert T. The Flight of the Cormoran. New York: Vantage Press, 1970.

Wilson, Hugh R. Hugh R. Wilson, US Secretary of Legation in Switzerland to Robert Lansing, US Secretary of State, 4 March 1918. “The Chargé in Switzerland (Wilson) to the Secretary of State.” Telegram. Foreign Relations, 1918, Supplement 1. Part I: Continuation and Conclusion of the War. Edited by Joseph V. Fuller. Pages 147-149. File No. 763.72119/1434. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1933.