Ancient CHamoru Cultural Aspects of Fishing

Fishing was one of the most important subsistence activities in ancient CHamoru society. Surrounded by the ocean, the CHamorus relied on their fishing skills to obtain fish, shellfish, turtles and other marine resources necessary for their survival. The CHamorus had different tools, beliefs and cultural practices specifically related to fishing, as well as rituals that helped ensure their efforts were successful.

Archeology has uncovered artifacts and ecofacts (remains of once-living things used by humans) of CHamoru fishing activities, but historical accounts by early European visitors provide more information about the cultural aspects of fishing. By examining accounts of ancient CHamoru fishing practices, we can get a sense of the native belief in the supernatural and the intervention of spirits to help them obtain a good catch, as well as certain behaviors related to fishing that reflect other social and cultural values held by the CHamoru people.

Fishing in CHamoru society

Customs and Rituals

Customs collectively are the traditions and accepted ways of behaving or doing something. Customs often include ritual practices. Rituals in general are formal or stylized acts that people perform in special places or at specific times. They are social acts, repeated and transmitted across generations. Usually, they are structured around religious beliefs, but the motivations and actions for rituals are varied. Rituals may be performed individually, or as a community; they may be private or public. Rituals help enforce social bonds or teach specific cultural lessons. They include rites of passage that signify major changes in an individual’s life. Studying rituals or ritualized behaviors can tell us about the people who participate in these activities and about the society or culture in which rituals are performed. In addition, rituals often shed light on deeper beliefs, superstitions, anxieties and taboos of a particular culture.

Early historical accounts of the ancient CHamorus describe the natives as very skilled fishermen. Fish and other foods from the sea not only provided a source of sustenance for the CHamoru people, but they were also important culturally, providing natural materials for tools and commodities for trade or gifts. Fish obtained by CHamorus living along the coasts could be traded for tubers, fruits and other agricultural products from inland CHamoru villages. Turtle shell could be fashioned into a kind of money called alas that were also were used for peace exchanges after warfare. Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora, a Spanish friar who jumped ship and lived among the CHamorus on Rota in 1602, wrote:

As far as their fishing skills and devices are concerned, it would take a very long story to tell about them; consequently, I will only say that they use the same kinds of nets and fishing tricks that our people use, and many more. When it comes to fishing from their funeas [boats], no better seamen or divers have ever been known to exist.

But not everyone in ancient CHamoru society engaged in fishing activities. The ancient CHamorus had strict rules about who could fish, and where. Fishing from boats and deep sea fishing were men’s activities, and these were skills learned at very young ages. Fathers would teach their sons, beginning around the age of four or five, taking them out with them in smaller versions of the large outrigger canoes. By the time sons were young teenagers, they knew enough to be able to go out to sea in their own boats and fish by themselves. Women and young children, on the other hand, would gather crabs, shellfish and other food items from lagoons and sandy flats within the reef.

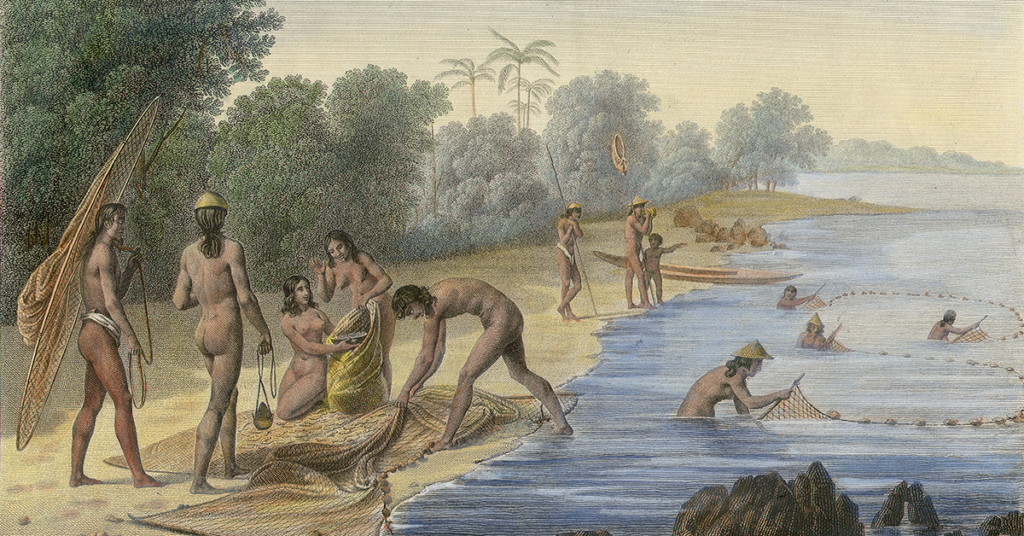

Early settlements probably had small enough populations such that gathering or foraging methods were sufficient for collecting food. However, as populations grew, more sophisticated fishing methods emerged. Net fishing, hook-and-line fishing, and the use of fish weirs or traps, known as gigao, developed and required participation and coordination of both men and women. Images from the Freycinet expedition in the early 1800s depict fishing scenes showing men and women working cooperatively to catch fish using nets.

Only elite CHamoru classes had the privilege to fish in the open sea. The lower class manachang were not allowed to touch the sea or canoes, as they were believed to bring bad luck; instead, the manachang could fish for freshwater eels (asuli)—a fish that upper caste chamorri would not eat, “on account of some superstition.” Fray Juan Pobre wrote that fishermen would not eat shark, which was seen as their enemy, and that elite or high status chamorri refused to consume tough scaled fish or freshwater fish from rivers and streams.

Access to particular fishing grounds was regulated by clans. Different fishing grounds had names and ownership of the area of ocean and associated reefs was organized around matrilineal lines of descent (i.e., inheritance from the female or mother’s side). Violation of these boundaries was punishable by death. Wars between clans would be fought to gain access to particular fishing grounds.

Other fishing customs

Fishing was both an individual and a communal activity for the ancient CHamorus. Fray Juan Pobre wrote about how the islanders worked together to catch fish and then share their catch with other members of the village.

According to archeological finds, parrotfish was one of the most abundant fish species caught and eaten by the CHamorus. Fray Juan Pobre described how the natives would catch flying fish (gaga), which also were caught in large numbers.

To catch flying fish the fishermen would use a float line technique, utilizing gourds or calabashes. Sailing out as a group in their boats, each fisherman had his own float, to which he would attach a two-pronged hook with a thin cord. The hook would be baited with carne de cos (coconut meat) on one prong, and shrimp or small fish on the other. Each fisherman would watch his float and look for the telltale wiggling, indicating a fish had been caught. The first of the catch would be eaten raw, and then the second would be baited on a large hook attached to the stern of the boat, to catch other kinds of larger fish.

When fishermen returned from their expeditions, they displayed a signal or banner made of pandanus to indicate they caught something. The children of the village would wait for the fishermen to return, and upon their arrival, the oldest sons would take the boats out of the water and place them in the canoe house. The fishermen would then wash themselves with fresh water brought to them by their best friends, who would help wash their backs. The fishermen would lay the fresh catch upon cut palms placed over a woven mat in the cleanest spot beside their house, and cut open the fish. As a special gift, portions of the fish were distributed, including the blood and intestines, even the fat, to the children who helped bring the fish home. Pieces from the back of the fish were given to neighbors. The remaining part would be salted “according to certain ritual procedures,” according to Fray Juan Pobre.

Salted fish and cooking methods

Some fish were kept alive in small ponds until needed. Fish and shellfish were eaten dried or salted. Salted fish, as well as fresh, uncooked fish, were important food items presented at festive occasions or special gatherings. Although salting methods are not described, the ancient CHamorus used salt obtained naturally from the sea to cure fish. People knew when fish was being salted and took care to not disturb the process. Fray Juan Pobre wrote:

After the fish has begun to take the salt well, they tie a long cord from the door to a palm tree approximately eight or ten braças [a marine measurement equivalent to 1.6718 meters] away. The indios [CHamorus] will detour to the other side of the house when they see this sign because they know that there is fish being salted on the side where the cord has been strung.

Salted fish would be particularly important during the dry season when heavy winds and high seas would make fishing very difficult, and chances for successful fishing expeditions would be minimal. Sometimes fish would be placed in brine instead of being salted, and at other times fish would be baked. In particular, baked flying fish would be served to sick people.

Fishing seasons

Fishing was so important in ancient CHamoru society that even the calendar was influenced by fishing seasons. The ancient CHamoru calendar consisted of 13 lunar cycles, somewhat equivalent to the months in the modern calendar. For example, the month Umatalaf (March in the modern calendar) was the time to fish for guatafi (snapper); Umagahaf, the 13th month, was a time to catch hagaf (rock crabs, crayfish or shrimp). Ideally, February to April were good months for fishing for sesyon (rabbitfish), ti’ao (baby goatfish) and satmoneti (goatfish); May to June were months for net fishing for ti’ao and mañahak (baby rabbitfish); July through September for i’e’ (baby jackfish), ti’ao, and tarakitu (medium-sized jackfish); July through October for atulai (mackerel) and achuman (a small, tuna-like fish); and November to January for using spear and torch methods to catch mafute’ (emperors, a kind of snapper), guile (rudderfish) and palakse’ (parrotfish). Click to know…Ancient CHamoru Calendar

Demonstration of CHamoru values

One of the most moving aspects of CHamoru culture witnessed by Fray Juan Pobre in the early 1600s was the system of cooperation and sharing among members of CHamoru society. People helped each other with different kinds of fishing activities, whether it was net fishing or float line fishing. Anyone who asked for assistance with fishing, such as for catching mañahak, could not be refused. In addition, although the mangachang could not fish, any catch of fish was shared with them. This reflected the value known as inafa’ maolek, which is a recognition of the interdependence of people in the community and the desire to live harmoniously through mutual respect and generosity.

Fray Juan Pobre was especially moved by their compassion. He stated:

They are naturally kind to one another…On the day an indio is ill and cannot go fishing, his son will appear on the beach at the time the other village fishermen are returning. The latter will know that the father or brother is ailing, and, consequently, they will share some of their catch with him. Although he may have a house full of salted fish, they will give him some of the fresh catch so that he will have it to eat that day.

The distribution or presentation of fish or turtle catches also reflected the matrilineal practices and respect for women in ancient CHamoru society. Turtle or large fish catches, such as marlin, would be presented first to the successful fisherman’s wife, who in turn sent it to her closest female relative of higher rank. This would continue until the highest-ranking female relative was reached, who subsequently would divide the fish or turtle. Shares were sent to the lower-ranking women through whom the catch had passed.

Spiritual practices

Ancient CHamoru society had numerous superstitions, taboos and spiritual beliefs associated with fishing. Taboos are social or religious customs that ban or prohibit certain practices, spaces or things, or limit these to particular individuals or groups. For example, as mentioned earlier, the manachang were not allowed to navigate canoes or fish in the ocean, and were restricted to fishing in freshwater streams or rivers. The upper caste chamorri would not eat eels or fish with large scales. The superstition of bad luck associated with eating freshwater eels was noted by the Spanish Jesuit missionary Father Diego Luis de San Vitores, and also by Belgian Jesuit Father Peter Coomans. Father Coomans asserted:

However, regarding the fish called eels, they are hated by the Indians [CHamorus] so much when they see our people enjoying themselves when eating what the natives look upon as bad luck, they give signs of nausea. So, the Fathers and everyone else have decided to abstain from it, while they are getting to know more about the superstitions, more on account of the nausea than for a ridiculous abstinence.

In addition to these taboos, there was a great spiritual connection between fishing and the ancestral spirits, or manganiti, whom the CHamorus respected. Father San Vitores wrote:

With all this, the Marianos [CHamorus] have certain superstitions, especially when they are fishing, at which time they observe silence and great abstinence, either from fear of, or to flatter the anites [manganiti], which are the souls of their grandparents, so they will not punish them by keeping the fish away or by frightening them in their dreams, of which they are very credulous.

Father Coomans, too, described how CHamoru fishermen were:

extremely prone to superstitions: they observe silence; if they should violate this [rule], they believe that the prey will escape.

The manganiti were believed to reside in the skulls of the ancestors, which were used by the makahnas—the traditional healers or shamans—for special prayers and ceremonies. The skulls were kept in little baskets and the makahna would communicate with the manganiti to invoke favors from them for fishing or other daily activities, for healing, rainfall, or to seek protection from harm. The makahna would also warn fishermen when they could or could not go out to sea. Such reverence did the CHamorus have for their ancestors, Fray Juan Pobre wrote, that if a man went fishing, he would leave someone in charge, usually a family member or servant to ensure that the ancestral skulls were not disturbed, otherwise, the spirits would become angry and the fisherman would drown or be unsuccessful in his catch. Father Coomans also mentioned that during fishing expeditions, a rope would be stretched across the door of the house:

they call this a sacred thing: atota [i.e., taboo]. If anyone should trespass over during those fishing trips, it is a crime; if anyone does so it renders all fishing useless. Anyone who has placed even a small something in security behind the ropes, which is extremely rare, it is safe even during the long absence; they lay out the sacred rope between posts and if anyone should try and trespass, he is surely a criminal and undoubtedly deserving of being killed with spears.

Fray Juan Pobre further described how the skulls were used as tokens of good luck, especially for fishing. Offerings of fresh fish or turtle caught during fishing expeditions would be placed before the oldest skulls in a special ceremony, inviting the dead ancestors to eat with them. He wrote:

At that time, he first carries up his fish, then he removes the skulls from the little boxlike cases and sets them in front of the fish, and while performing certain ceremonies, he offers them the flying fish that he has caught. He speaks to them very softly so that no one can hear what he says. When he has caught a large fish, such as a blue marlin or mahimahi, or a turtle, or a parbo, which they call taga [snapper: tagafen saddok; red snapper: tagafi], he offers it to the skull. Then he puts the oldest skull on top of the others; then he removes it, and places it on top of whatever he has caught. Then the relatives and closest neighbors are summoned and they make a fiesta for their skulls, drinking ground rice mixed with water or with grated coconut milk. They then make signs and perform ceremonies, as if inviting the old skull to eat. Then, they begin to sing very loudly, as if giving thanks to the fisherman. They tell him, ‘You are much beloved, this head loves you very much. This skull loves you dearly because he has made you very lucky in fishing and he honors you so much.

Such strongly held beliefs in the power of the skulls were not easily removed, even with the introduction of Christianity in the late 1600s. However, Father San Vitores recounted one instance of how the CHamorus were experiencing the apparent conflict between the two traditional belief systems of Catholicism and ancient CHamoru culture. Here, a young boy, the son of a noble and educated by the missionary priests, influenced his father to call upon the Christian spirits to catch a fish:

This boy was 12 or 13 years old. He was the son of a noble. One day he went out fishing with his father in a small boat, bearing the banner of the holy cross, as he was accustomed to. The father saw a fish that the natives like very much, called guatafe, and without stopping to think, he was carried away by the old custom and began to invoke his anites, to gain their help in catching the fish. The boy was distressed at this, and weeping, said, ‘Father, don’t call to these enemies. You won’t catch anything.’ The father answered, ‘What can I say?’ ‘Invoke Jesus and Mary and you will catch the fish.’ He did so, and he had scarcely uttered these sweet names when he caught the fish. Then he came running to our house with his son, singing praises to Jesus and Mary, and telling what had happened to himself and his son and asking pardon for his thoughtlessness.

Such conflicts between Christianity and ancient CHamoru culture signaled the beginning of great changes for the traditions of CHamoru fishermen, many of who would eventually exchange their maritime skills and fishing implements for land-based skills in agriculture and farming tools. Nevertheless, reliance on and respect for the ocean and its resources remains an important part of CHamoru cultural history. In the ancient CHamoru mindset, the ocean was theirs, a part of their creation. This is exemplified in the statements made by Fray Juan Pobre’s companion, the shipwrecked Spaniard Sancho, who had asked his CHamoru informants who made the earth and the sky—and the ocean. The natives told him they made it—

…that inasmuch as they [the CHamorus] sail and fish on it, they have made it. Such is the foolishness with which they answer our questions, but they often say that we are foolish to ask.

For further reading

Amesbury, Steven S., Frank A. Cushing, and Richard K. Sakamoto. Guide to the Coastal Resources of Guam: Vol. 3. Fishing on Guam. University of Guam Marine Laboratory Contribution No. 225. Mangilao: University of Guam Press, 1986.

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation. Tiempon I Manmofo’na. Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. By Scott Russell. Micronesian Archaeological Survey No. 32. Saipan: CNMIHPO, 1998.

Coomans, Peter. History of the Mission in the Mariana Islands: 1667-1673. Translated by Rodrigue Lévesque. Occasional Papers Series, no. 4. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2000.

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

García, Francisco. The Life and Martyrdom of Diego Luis de San Vitores, S.J. Translated by Margaret M. Higgins, Felicia Plaza, and Juan M.H. Ledesma. Edited by James A. McDonough. MARC Monograph Series 3. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 2004.