Role of Education in the Preservation of Guam’s Indigenous Language

View more images for the Role of Education in the Preservation of Guam’s Indigenous Language entry here.

Editor’s note: Originally published in Kinalamten Pulitikåt: Siñenten I Chamorro: Issues in Guam’s Political Development: The Chamorro Perspective, by the Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1996, pp. 17-25. With minor updates, this chapter is republished in Guampedia with permission from the Department of CHamoru Affairs.

The goal of education in any society is to impart knowledge and to equip people with the tools necessary to become valuable and contributing members of their community. Yet, who determines what should be taught or what kind of knowledge people should acquire?

Throughout Guam’s colonial history, Spaniards, Japanese, and Americans strove to introduce and impose their value systems and beliefs upon the Chamorros. The methods each used may have been different, but the underlying assumption behind educating the natives was the same—that the Chamorros needed to be educated in what was considered the appropriate manner.

The first task that faced the colonizing powers was to teach the Chamorros the colonizer’s language, be it Spanish, Japanese or English. After all, how could Chamorros learn and assimilate, or be absorbed into a foreign culture, when the Chamorro language could not adequately express foreign concepts found, for example, in the Christian doctrine so fundamental to the Spaniards, or the vision of a “Co-Prosperity Sphere” that marked Japanese expansion during World War II? How could Chamorros, who had lived in a society based on ranking and status, comprehend the American concept of democracy? Thus, the first casualty of the various attempts to colonize Chamorros, to superimpose foreign values and rules, was the Chamorro language.

Fluency in Spanish, Japanese or English virtually guaranteed a relatively high status or position, especially a well-paying job. As no educational system can effectively educate without the use of a common language, the primary emphasis throughout the different colonial administrations was the language arts. Education of the Chamorros was not connected to Guam’s cultural identity. This fact is ironic if the goal of education is to equip students with the necessary tools to become valuable and contributing members of the community. After all, how effective could a system of education be when it was not connected to the history and cultural identity of Chamorros?

In this article, I will focus on how the teaching of a non-native language supported the policies of domination by the different powers in Guam. I will also explore recent attempts to preserve the Chamorro language by its incorporation into the public school educational curriculum.

Ancient Chamorro Era

Before reviewing the Spanish, Japanese and American practices, it should be noted that the Chamorros had an institution that trained young boys and girls to be productive members of Chamorro society. In the guma’ uritao, master craftsmen and artisans taught boys the skills of hunting, planting, fishing, navigation, canoe building, and tool making. The guma’ uritao was also a place where girls and boys learned who they were in relation to others in their community. In a small and close knit community, an individual’s identity is framed by his or her relationships with others. Thus, Chamorro adolescents were taught their genealogy, that is, information about their ancestors.

Chamorros were also taught history in the guma’ uritao. Because Guam did not have a system of writing, history was preserved through stories, chants, songs and legends. Boys learned to be good storytellers, debaters and orators and compete in formal contests using skills. Girls also polished such skills and engaged in their own unique forms of public singing and chanting competitions. Today, one form of this remains today called Kantan Chamorrita.

The guma’uritao was also a place where Chamorro adolescents learned to have sex, a very practical matter if those adolescents were to have families and propagate the Chamorro race.

Thus the Chamorro people had a system in place to bring adolescents into the mainstream of adult society. Young Chamorros were taught not only who they were but how to live with and amongst each other as productive members of society.

Spanish Era

With the arrival of the Spaniards came a missionary zeal to introduce Catholicism to the Chamorros. Education was made available to Chamorro children so they could recite and practice Christian doctrine. Indeed, the first school founded by Father Diego Luis de Sanvitores in the 17th century was a seminario for boys called Colegio de San Juan de Letran. The first students were the sons of chiefs and included the son of Tomas Bougi, the chief of the city of Hagåtña. A separate school for girls was also established, La Escuela de las Niñas. This segregation of boys and girls reflected the missionaries’ belief that boys and girls should not be together prior to marriage. The establishment of the first Spanish schools was aimed at abolishing the guma’uritao, the young men’s training grounds. Instead, students were taught to speak, write and read the Spanish language:

San Juan de Letran was a boarding school for children from ages 7 to 14. Its students were taught the Christian doctrine with the goal of having them return to their villages upon graduation to serve as assistants to the priests and serve as catalysts for the conversion of the Marianas to the Catholic faith. Although the missionaries had high hopes for the school, other officials later felt that there were problems associated with introducing such institutions and having such high expectations of the natives. By the 19th century, for instance, other Spanish officials began to oppose the school. For example, in 1830, Governor Francisco Villalobos expressed this concern to his superior, the Viceroy of Manila:

‘It is my opinion that it is better to do away with such establishment (San Juan de Letran). The children who live there very soon forget their own misery and poverty and get accustomed in the five, six or more years they live there to good food, dress and shelter. They do not learn an occupation which will help them to survive after they are dismissed from the school, and they get accustomed not work… they are only worthless young men, with nothing to do.’

M. Del Priore, Education on Guam During the Spanish Administration from 1668-1899

Governor Villalobos opposed the seminary because he thought that it only made the Chamorros lazy and unproductive. In this erroneous sense held by Villalobos, the school did not accomplish the goals for which it was intended. The intention of this early school under the Spanish colonial system was precisely to wean Chamorro children from their native institutions and indoctrinate the them so that they could serve as valuable assistants in the work of the missionaries. Villalobos believed this was not working because the converted and educated Chamorro was only becoming lazy as a result. On the contrary, the newly “educated” Chamorros did not simply become lazy, though they did undergo some profound changes in values, tastes and probably status.

Although teaching the Spanish language served the Catholic Church’s interests, it is worth noting that the Church showed great interest in the Chamorro language. Sanvitores, for example, tried to learn the Chamorro language and even preached his lessons in it. Throughout the next 200 years, Sanvitores would be followed by other priests who would exhibit interest in the Chamorro language. In the early 20th century, for instance, Spanish Capuchin priest Pale Roman de Vera wrote a book of hymns and prayers in the Chamorro language.

Viewed in this light, the Spanish attempt to Christianize Chamorros became successful once the Chamorro language was used in church activities.

A new colonizer

After defeating Spain in a war in 1898, the United States acquired Guam to serve as a coaling station and American outpost in the Far East. Even before the Treaty of Paris with Spain was ratified by the US Congress, President William McKinley directed the Department of Navy to secure the island. The Navy proceeded to establish a US Naval Government of Guam, which lasted until 1950—with the exception of the nearly three-year period during World War II when Japan invaded and occupied the island. After cleaning up the island to make the place “liveable” for itself, the Naval government of Guam quickly turned to educating the natives in order to better accommodate its needs. Education centered not only on the three “R’s” (Reading, ‘Riting, and ‘Rithmatic), but more importantly, on teaching the English language as the primary means to Americanize the Chamorros.

Japanese Era

In December 1941, at the outbreak of World War II in the Pacific, Japan invaded and occupied Guam until July 1944. Though different than the circumstances under which Spain and America arrived, the Japanese colonial period in Guam featured the very same colonial objectives to claim control of the island and exercise political authority over the Chamorros. And like Spain and America, Japan proceeded to exert its rule by imposing its language and culture. As quickly as they arrived, the Japanese imperial army and occupation unit implemented an educational program using their language. Children between the ages of 7 to 16 were assembled in the respective schools in the outlying districts and in Hagåtña. They were taught the Japanese language by rote. Music and recreation also were taught.

The Japanese also started a boarding school for adult men and women and some young people. Three civilian Japanese instructors were brought from Japan for this special school. The men and women were segregated from each other in separate dormitories but were brought together for all instructional and recreational activities. The school was located in the houses of Atanacio Perez and Jose Salas in Hagåtña. The students were divided into three groups of 25 each, and after three months, they were assigned to the various Japanese offices and schools. The third group did not complete the entire training program because the American shelling and air raids which began in 1944 interrupting the educational process.

US Naval rule

The pattern of discouraging the use of the Chamorro language continued with the Americans governance of Guam. Signs which read “Speak English Only” were posted in offices, schools and on public buildings. The official English-only policy created a direct link between proficiency in the English language and economic gain and status. Indeed, there was an elite group of Chamorros who served in high-ranking roles simply because they could read and write in the English language. Their families enjoyed a standard of living far better than those families who did not learn the English language. I remember very clearly my father telling us that although he only reached third-grade reading level, he became a teacher and then served on the Naval governor’s staff.

The early American educational system was a reflection of the American “melting pot” theory—that people from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds can blend together to become similar or American. This melting-pot concept forced waves of immigrants with different values and backgrounds to mold their behavior to conform to American norms. This may be a way to view the early American educational system in the US as well as in Guam.

People of the prewar generation were made to believe that without proficiency in the English language, the chances of obtaining gainful employment were unlikely. This belief was reinforced in a variety of ways, such as the establishment of a school for Americans only, located near the Plaza de España across what is now the Hagåtña Mayor’s office. Only the children of military and civilian parents were allowed to attend the school, which was considered superior to any school Chamorros attended. The practice of segregated schools for elementary and middle schools continued up to World War II.

It is interesting to note that although there was no compulsory education during the Naval administration, there was tremendous incentive to attend the American schools. In Hagåtña, the schools were named Dorn Hall, Leary and Seaton Schroeder, after the Naval governors, and Padre Jose Palomo, after the first Chamorro Catholic priest. These were all elementary schools. The curriculum was basically the “3 R’s,” along with geography, science and physiology. Success was measured by the ability to be Americanized. Students were also required to endure compulsory calisthenics to the music of the Navy band at the Plaza de España 15 minutes before classes started. When a student reached the high school level, he or she attended the George Washington High School.

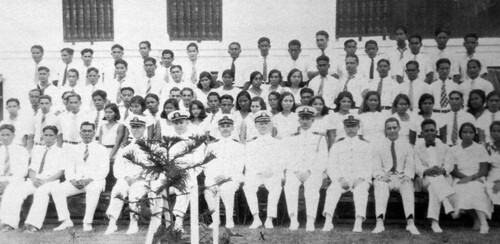

As part of its education before the war, the American Naval government sought to instill the values of cleanliness and patriotism. Naval officers in crisp white uniforms directed the bulldozing of Guam’s jungle growth to make Guam a neater place to live.

Before World War II, when the Spanish priests were replaced by the American clergy, American priests followed the practices of their predecessors and learned Chamorro. They communicated with the Chamorro people in their daily interaction and delivered their homilies in the native tongue. Prayers were recited and hymns were sung in Chamorro. The interest of the Catholic Church in using the Chamorro language continued and the Church assumed a custodial role in maintaining the native language.

After the American armed forces recaptured Guam from the Japanese in 1944, however, the use of the Chamorro language diminished. The English-only policy was reinforced not only by the Naval government but also by the Catholic Church. By the mid-1940s, the Americans brought in American priests and nuns, and even American bishop Apollinaris W. Baumgartner to lead the Church. While the Spanish priests incorporated the Chamorro language into the prayers, hymns and novenas, the American Catholic nuns discouraged use of the Chamorro language.

Bishop Baumgartner had brought the Mercy and Notre Dame nuns to staff the private Catholic schools, and the instruction in the English language policy was adopted. It was then that the Eskuelan Pale (catechism) classes began to be conducted in English. Whether it was intentional or unintentional, the Catholic Church in Guam discarded its custodial role to preserve the Chamorro language.

Compulsory English and the emulation of American culture facilitated the Americanization of the Chamorro people, which was seen as the way to facilitate America’s interests in the region. The Spanish mestiza, the old-time dress of Chamorro women was abandoned in favor of western style dresses and the Chamorros acquired a taste for American food.

Chamorros were encouraged or required by economic necessity to assimilate to the American culture and to speak the English language. They gradually began to view their culture and language as inferior. Perhaps this is the hallmark of the success of colonialism: when indigenous people abandon what is theirs in favor of taking on what is foreign. This colonialist mentality came to play a large role in obstructing subsequent attempts to redeem the Chamorro language and culture.

In the 1970s, Guam’s legislators encouraged the use and teaching of the Chamorro language. The late Senator Frank G. Lujan sponsored Public Law 12-31, which authorized the Board of Education to initiate and develop a bilingual/bicultural education program emphasizing the language and culture of the Chamorro people. Senator Paul J. Bordallo authored Public Law 12-132, which made both English and Chamorro the official languages of Guam.

With this legal framework in place, the Department of Education designed a bilingual/bicultural education program to begin teaching the Chamorro language in Guam’s schools. The next step was to secure the funds to get the program going. Fortunately, Guam qualified for funding under two particular federal laws: the Elementary Secondary Education Act (ESEA) and the Emergency School Aid Act (ESAA). These laws were aimed at addressing the special needs of ethnic minority students in the US. ESEA provided federal funds to US school districts for programs using the languages of minority students as a means for learning the English language. ESAA, meanwhile, funded programs to promote the heritage of the different ethnicities in the United States.

Guam applied for and received both ESEA and ESAA funds to teach Chamorro concurrently with English. However, despite these resources, the island was at a disadvantage because Guam’s ethnic language and heritage had never been part of the overall education program. There were no Chamorro books or learning materials available to teachers and students. And, because of the historic emphasis on the English language, most of Guam’s students could not read, write or even speak Chamorro. Despite these drawbacks, the department tackled the crucial task of teaching students how to speak Chamorro, as well as how to read and write it.

ESEA funds were used to formulate a pilot bilingual program for the primary grade. Under the direction of Sister Ellen Jean Klein, SSND, the pilot program began with two small bilingual classes at Price and Torres Elementary Schools. These classes were limited to 25 students each. Since there were no Chamorro language curriculum and instructional materials available, Lagrimas Untalan, an educator and former legislator, produced simple illustrated books for use in the classrooms. Untalan was very much a pioneer in the teaching of Chamorro language and culture in Guam’s schools.

As associate superintendent of Curriculum and Instruction, I (Pilar Lujan) used a grant from the ESAA to expand the Chamorro language and culture program to several other public elementary schools, as well as to the private Catholic schools. Clotilde Gould was assigned as project director for this special program and several native Chamorro speakers were hired to serve as language teachers. However, since the Chamorro speakers were not certified teachers, the Territorial Board of Education was at first reluctant to approve the hiring. The Board’s hard-won approval marked the first formal recognition of native Chamorro speakers in the language teaching profession in Guam.

As the Chamorro language and culture program expanded into the high schools, the need for more advanced learning materials followed. The task of developing Chamorro books and instructional materials was undertaken by DOE’s Office of Curriculum and Instruction, which drew information from Chamorro legends and oral histories and from the Chamorro language studies of an American linguist named Donald Topping. Chamorro musicians, most notably Carlos Laguana and Johnny Sablan, were enlisted to write Chamorro music for use in the program as well.

Since the Chamorro language was largely only a spoken language, developing written materials for classroom use proved to be a challenging and controversial task. Until then, the most common forms of written Chamorro were translations of Catholic hymns, prayers and novenas produced by Spanish priests in the previous two centuries. These translations were based on the alphabet and limited sound system of the Spanish language, which could not accurately accommodate many of the sounds unique to the Chamorro language. A classic example of this limitation is in the village name Yona. The true Chamorro pronunciation of “Yona” bears little resemblance to its Spanish spelling.

To complicate matters even further, the imposition of American English and its spelling and sound system for more than half a century have profoundly shaped the way Chamorros think of oral sounds in terms of American English letter symbols. But even the American alphabet and sound system cannot accurately accommodate the sounds unique to the Chamorro language. Take the example “Yona” again, the “y” sound of American English is incorrect both in the Spanish spelling of this word and in the Chamorro pronunciation of it.

Attempts to address these linguistic problems and devise a more accommodating and accurate sound/spelling system of the Chamorro language were made by the Marianas Orthography Committee in the late 1960s. At this same time, Donald Topping was already conducting extensive research into the Chamorro language in Guam, Rota, Tinian, and Saipan. Topping was then a professor of English at the Territorial College of Guam. He later used his linguistic research as his doctoral dissertation and produced the first comprehensive studies of the Chamorro language, including a dictionary, a grammar reference and a textbook. These works complied with the spelling principles adopted by the Marianas Orthography Committee in 1971.

The Marianas Orthography Committee, which included representatives from Guam and the Northern Marianas, was followed by the Guam Chamorro Language Commission. The Northern Marianas also has an official language commission. The Guam Chamorro Language Commission was created to undertake a formal study of the Chamorro language and to devise an orthography standardizing the written form of the Chamorro language. This orthography was then to be adopted officially by the Guam Legislature.

In the mid-1970s, the Chamorro Language Commission enlisted Dr. Fe Aldave Yap, a linguist from the Philippines to develop an orthography. With extensive input from teachers in the bilingual program and from Lolita Leon Guerrero Huxel, a Chamorro linguist and University of Guam professor, Dr. Yap devised a Chamorro orthography based on Asian spellings and sound systems. But because it offered many unusual spellings, Dr. Yap’s orthography stirred up angry sentiments among the public and it was rejected for official adoption by the Guam Legislature. Governor Ricardo J. Bordallo issued an executive order adopting the orthography, but so much criticism was leveled against him that he rescinded the order shortly afterward.

Guam still does not have an officially adopted Chamorro orthography. [By 1999, Public Law 25-69 was passed, which repealed the law establishing the Chamorro Language Commission, and transferred its functions to the newly created Department of Chamorro Affairs.] However, Dr. Topping’s orthography remains in wide use by students and language enthusiasts.

In addition to the programs implemented by the island’s school system, other efforts to promote and encourage the Chamorro language included televised Chamorro language lessons by Dr. Katherine B. Aguon on KUAM and a 15-minute Chamorro news broadcast, anchored by Pilar Lujan on KGTF, Guam’s public education television station. KGTF also initiated and aired Chamorro programs for children.

Yet, despite all the groundbreaking efforts of dedicated individuals, the Chamorro education program was not readily accepted by the community. Even the administrators of the schools in which Chamorro classes were being taught were reluctant to support the program. After over 300 years of foreign language instruction at the expense of the Chamorro language, many people questioned the validity and utility of the Chamorro courses. Many parents felt that learning the Chamorro language was of little practical value, since learning it would not open employment opportunities for their children. Similar sentiments were expressed by the academic community at the University of Guam. Some professors and university officials questioned the relevance of Chamorro language instruction in modern society, especially because many considered Chamorro to be nothing more than a “dialect” and not a true language. Opponents of the language program felt that academic studies of the Chamorro language simply were not credible, despite Dr. Topping’s studies, which revealed that the Chamorro language did indeed have the unique geniuses and properties embodied by other languages in the world. [Update: The University of Guam now has a BA program for Chamorro Studies.]

Resistance came from the media as well. Guam’s print and electronic media were English-oriented and made little room for the promotion and encouragement of languages other than English. The Pacific Daily News, Guam’s only daily newspaper, adopted the policy requiring any non-English advertisement or announcement to be accompanied and published with English translations. This policy later prompted a protest demonstration by Chamorro language activists.

The general resistance to the Chamorro language program was a direct result of Guam’s colonial mentality. This mentality reflected the extent to which the Chamorros had internalized the views of their colonizers. Those views, of course, held that imported foreign values were “better” than indigenous ones, and that English was superior to Chamorro. After nearly a hundred years of this message, many Chamorros grew insecure about speaking their own language. Some were even afraid that the formal teaching of the Chamorro language in schools would have negative effects in the modern world. The negative reactions of academics and the media may be viewed as a reluctance to relinquish the control established by decades of an English-Only policy.

Perhaps it was due to the perseverance and dedication of the Chamorro program pioneers, or perhaps it was the worldwide winds of nationalism blowing also in Guam, that the Chamorro language program gradually gained acceptance. Or perhaps it was because the American “melting pot” concept gave way to the concept of multiculturalism.

The “melting pot” concept held that immigrants to the US should forsake not only their political allegiance to their mother countries, but also their languages and cultural heritage in order to become “full-fledged Americans.” However, later waves of immigrants began to rebel against this idea. Many could not give up their ethnic identities in favor of an “American” identity (which in itself, was a strange amalgamation of many different ethnic identities). Many, especially from Latin and Asian countries, also refused to allow their language to be subsumed by the more dominant American culture, with its heavy Anglo-European emphasis. The demands by ethnic minorities for recognition and acceptance gave rise to the philosophy of multiculturalism and to the enactment of federal laws such as the ESEA and the ESAA.

America’s new awareness to ethnic and cultural differences prompted many Guam leaders and educators to champion the Chamorro cause more confidently and systematically. In 1977, under the leadership of Senator Franklin J. Quitugua, Public Law 14-53 mandated the teaching of Chamorro in all public elementary schools. Within the Department of Education, the original Chamorro language and culture program expanded into the Chamorro Studies Research Division. At the University of Guam, Chamorro language instruction was offered to students and teachers in the Teacher Corps program. Guam’s media also became more sensitive, and radio and television audiences were treated to more Chamorro programming. At the Pacific Daily News, a series of angry letters to the editor and a public protest demonstration forced a change in advertising and editorial policies; ads and announcements in Chamorro or any other non-English language were no longer required to be accompanied by English translations unless desired. Chamorro speaking news reporters were also encouraged to print the quotes of Chamorro interviewees.

As part of the PDN’s new found sensitivity to the Chamorro language, Executive Editor John M. Simpson encouraged several Chamorro writers into the newsroom and with his wife, Carol Simpson, an instructor at the University of Guam, worked toward including introductory journalism and news reporting classes among the university’s course offerings. John Simpson also approached the Department of Education with an idea to produce a “Peanuts-type” Chamorro comic strip, similar to the comic strip by Charles Schultz, which the PDN could then feature on a daily basis, along with the paper’s other comics. Education Director, Katherine B. Aguon, supported Simpson’s idea and instructed DOE’s Chamorro studies division to develop it. Rather than merely copying a strip like Peanuts and translating it into Chamorro, Chamorro studies administrator Clotilde Gould suggested creating a uniquely Chamorro comic strip, Juan Malimanga, based on a well known figure of Chamorro folklore, as the main character. Together with the Division’s artist, Roger Faustino, Gould and her staff then produced Juan Malimanga and a short Chamorro language lesson for the Pacific Daily News. “Juan” and the language lesson still appear in the PDN’s comic pages.

Since its advent in the early 1970s, “Chamorro Week,” an idea inspired and developed by Dr. Robert Underwood and former DOE Director Elaine Cadigan, also has been institutionalized in Guam’s schools. Today, the annual celebration of “Chamorro Week” reflects Guam’s ongoing efforts to “mainstream” the Chamorro language and culture. [Update: Chamorro week has since been expanded into Chamorro Month.]

Yet despite the many obstacles which have already been overcome, there still remains some resistance to the teaching of the Chamorro language in the public schools and at the University of Guam. Although Guam laws now mandate Chamorro courses at all grade levels, school administrators still do not give the Chamorros studies program equal instructional time, nor do they provide the same classroom spaces that are given to other class subjects.

Entrenched policies

Unless colonial social and political policies are removed, Chamorro language and culture will continue to be denied their rightful status in all institutions affecting this community. We have seen and experienced how the colonial educational policies of the last 200 years have suppressed Chamorro language and culture. We have seen and experienced how the American school curriculum has been embraced with complete and unquestioned acceptance. Chamorros themselves have given only lukewarm responses to preserving Chamorro language and culture through training in our educational institutions. The colonial policies entrenched in our system have, and will continue to, negate the implementation of an effective and genuine Chamorro language and culture agenda.

Many Chamorros still equate success in school with proficiency in the English language. The notion that only the knowledge of English can lift the Chamorros out of economic and social oblivion has been most damaging to their language and culture. How can we prove it false? In continually advocating that personal economic success is the ultimate consequence of learning English proficiently, our schools are overselling English. Since it has never been in the mission of our educational institutions to Chamorrocize Chamorros, how can our schools reverse the firmly established colonial policies intended to Americanize Chamorros?

The efforts to retain the Chamorro language through formal education have grown out of self-preservation. Today, federal programs speak in terms of cultural awareness and respect for cultural diversity. The new attitude is that having a particular ethnic identity is not compatible with being an American. This philosophy assumes there is a dominant culture and ethnic minorities are in danger of being subsumed by it. Our schools have been quick to adopt this new philosophy and to implement the federal programs without questioning the rationale for their development, adjusting them to meet local needs.

In Guam, the dominant group is Chamorro. But it is their culture that is in danger of extinction, not those of other ethnic groups. Guam’s various ethnic groups arrived with firm knowledge of their respective cultural heritages; they speak their mother tongues proficiently. Their own educational institutions have armed them with with strong identities and language, which, under today’s educational philosophies, are appropriate vehicles for learning English as a second language. Chamorros do not have these advantages, despite their ethnic dominance. Guam is not a “melting pot.” Its minority groups are not in danger of assimilation by Chamorro society. But like the Chamorros, they are expected to conform to the cultural pattern imposed upon Guam society by American colonization.

In order for Chamorros to affirm their existence on the basis of indigenous rights, their educational institutions must be free of the colonial policies which dilute their efforts to promote their language and cultural rights. Education in Guam must be Chamorrocized. Younger generations of Chamorros certainly want this. They want to know the cultural fabric that enables them to identify with Chamorro values and traditions. They want to be as proficient in their own language as they are being made to be in English. They cry out for dignity and respect, for recognition and acceptance of their heritage.

Chamorros have come under colonial domination for no other reason than having been born on a small but valuable piece of real estate. Despite their tragic history, they still have first rights to the land, air and water in their homeland. They do not need to argue the validity of their birthrights.

By Pilar C. Lujan