Physical Anthropology of Ancient Guam and the Mariana Islands

Least studied

Of the different regional groups of the Pacific, the physical anthropology of the peoples of Micronesia is probably the least studied. While archeologists have collected human skeletal remains from Micronesia for examination since the beginning of the 20th century, much of the current understanding of the physical anthropology of the region was developed in the 1980s and 1990s.

Most of these studies have been conducted with Chamorro/CHamoru skeletal remains from the Mariana Islands. These remains were collected from archeological excavations completed in the 1920s by Hans Hornbostel and JC Thompson, who were employed at the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawai`i.

Other sets of skeletal remains have been recovered from various sites throughout the islands as contract archeological projects from the construction of hotels and roads. However, the overall lack of skeletal materials available for study, as well as the often poor preservation of human skeletal remains due to deterioration from long exposure in tropical climates, have contributed to the dearth of scientific studies on the physical attributes of Micronesian peoples, especially from pre-contact times.

In recent years, the repatriation of human remains to indigenous groups for reburial also has limited the access researchers have to skeletal materials for extensive anthropological research. The remains of Chamorros from Guam and Saipan housed in the Bishop Museum were returned as well, and subsequently were reburied or prepared for reburial. However, examination of the remains from the Hornbostel collection by different researchers from the United States, Japan and Guam over the years, as well as remains from more recently excavated sites, have offered a glimpse of the physical stature, cultural aspects and environmental challenges faced by Chamorros in the course of their long history in the Marianas.

Brief history of physical anthropology in the Mariana Islands

Physical anthropology is the specialization of anthropology that examines human biology in the context of evolution, with an emphasis on the interaction between biology and culture. It often relies on, but is distinguished from archeology, which is the anthropological subdiscipline that studies the cultural artifacts and material remains from early or past societies. Modern physical anthropologists are largely concerned with biological differences expressed among various human populations as societies undergo cultural change or adapt to local environmental conditions and challenges, such as cold, heat or high altitude. The populations may be of past or contemporary societies. Physical anthropologists also look at nutrition and the relationship between diet and other aspects of human physiology, including health and disease, fertility, growth and development.

Studies of the physical anthropology of Chamorros rely heavily on techniques developed in archeology and osteology, or the study of human skeletal remains. Bone biology and physiology can reveal much about the environmental challenges or physical conditions individuals or populations had to contend with over the course of one’s lifetime, including physical stresses from culturally related activities, or nutritional stresses from periods of famine or disease. This is because such stresses may leave lasting marks on bones or teeth. Indicators for age could include the presence of arthritis; nutritional deficiencies may be indicated on tooth enamel or markings on growth areas on the long bones of the arms or legs; behavioral stresses such as heavy lifting or squatting for extensive periods of time can also be indicated by signs of wear or change in bone shape at particularly stressed points like the junction sites for tendons or ligaments. Wear on teeth, calcareous or calcium deposits, or staining can indicate diet and, in the case of the Chamorros, specific cultural practices, such as the chewing of pugua or betel nut with lime.

In the mid-1920s, a large collection of skeletal remains and cultural artifacts were excavated and removed from various archeological sites in the Mariana Islands. The materials were then sent to Hawai`i and housed in the Bishop Museum, where they remained for more than 70 years. The collection is known as the Hornbostel Collection, named for the Bishop Museum employee, Hans Hornbostel, who brought these remains from the Marianas to Honolulu.

In the last months of 1999, parts of this collection, mostly human skeletal remains from Saipan, Tinian and Rota, were repatriated to the government of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), where they were reburied. The remains that were excavated on Guam were also returned, but are still housed at the Guam Museum awaiting processing and reburial. It is estimated that the Hornbostel collection contains the remains of at least 400 different individuals, some of which are believed to be over 700 years old—pre-Spanish or early post-Spanish contact. There are also Chamorro remains that were removed and sent to museums in Germany and Britain, but the most widely studied materials come from the Hornbostel collection.

Hornbostel was not a trained archeologist, and in fact, age biases in his sample of human remains of adult skeletal materials over children reflect his selective method of recovery for only the best preserved materials or the most recognizably human remains. His collection, however, also consisted of an array of material and cultural artifacts, including latte, weapons, fishing implements, pottery and stones with petroglyphic markings, as well as his own extensive fieldnotes, which were of excellent quality and detail surpassing those of subsequent archaeologists.

Anthropologist Laura Thompson who worked for the Bishop Museum in the 1930s published a report describing the Hornbostel collection and his fieldnotes, but made little mention of the skeletal remains. It is not clear how many researchers have actually studied the Hornbostel collection, but a few notable reports have been published, including work done by R. W. Leigh (1929); Wood-Jones (1931); Steward and Spoehr (1952); Hanihara (1986), Suzuki (1986); Koizumi (1986); Brace, et al. (1990); Dodo (1986); Turner (1990); Pietrusewsky (1990a, 1990b, 1994a); Ishida and Dodo (1997).

Rona Ikehara-Quebral also conducted extensive analysis of the Hornbostel collection. Most of these published works involve comparative analyses of Chamorro skeletal morphology or structure with other Pacific and world populations, dental studies, and paleopathological and paleoepidemiological studies dealing with health, death and disease.

More recent studies in Marianas physical anthropology in the 1990s are based on human remains recovered by contract archeologists working in sites of urban development, such as hotel or resort and road construction sites, and cultural resource management projects from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. Most of these remains are from the transitional period from pre-Latte to Latte eras of Chamorro history. Because these remains have been recovered from construction sites rather than from directed archeological excavation projects, there are biases and gaps in the kinds of materials recovered, as well as biases that may be reflected in the types of diseases or environmental stresses expressed in the remains.

According to Hanson and Butler, the research questions pursued in the study of these remains are often linked with the general questions proposed by cultural resource management in the Marianas, including: subsistence or diet adaptations, especially in relation to marine and terrestrial food sources and the role of deep sea fishing in Chamorro populations; settlement patterns and adaptations on the coasts and in inland areas over time; and the impact of storm events on coastal sediments.

The often poor preservation of these skeletal materials, though, the lack of standard methods of studying these remains, as well as the need to return the materials out of respect to the Chamorro people has presented challenges to answering these questions. However, researchers have worked hard to piece together a viable description of the physical anthropology of the Chamorro people from the Marianas, and Guam in particular, making the Chamorros the most studied of the populations of Micronesia.

Some aspects of physical anthropology of ancient Chamorros

General health and stature

The Chamorro people are believed to have originated from Southeast Asia in a wave of migration that began over 3,500 years ago. Over the centuries they developed the unique culture that the Spanish eventually encountered and described in the early years of European exploration. One of the first written descriptions of the physical appearance of the Chamorro people is by Antonio Pigafetta, a crewmember on Magellan’s expedition, which landed on Guam in 1521. He described the Chamorros as :

…tall as we, and well-built…They are tawny but are born white. Their teeth are red and black for they think that it is most beautiful…They [the women] are good-looking and delicately formed and lighter complexioned than the men.

Other accounts marvel at the apparent strength of the Chamorro men, asserting them as one of the strongest ever seen. One early chronicler told of an incident in which a Chamorro man, separated from others, was attacked by Spaniards in an attempt to take him back to their ship.

Instead he (the Chamorro) grabbed them all, dragging them along as he ran off, and before he would free them, it was necessary for others to threaten him from above with arcabuces.

Studies of Chamorro skeletons show cranial and facial features reflecting an Asian heritage. They indicate an average height of males ranging from 168 to 175 centimeters (about 5’5” to 5’10”), with some individuals reaching over 6 feet. The women were smaller, however, measuring about 152 to 160 centimeters (about 5’2” to 5’6”). For the 16th century, the Chamorro people were quite tall, especially among Asian and European populations. Studies of a pre-contact site in Apurguan, on the west coast of Guam between Hagåtña and Tamuning found an average male stature of 173.1 centimeters (5’8”) and 161.3 centimeters (5’3”) for females.

Chamorros were also of relatively good health, with many individuals reaching adulthood and even advanced age. According to Spanish accounts, they used herbal medicines and massage techniques to cure various ailments. The Chamorros, however, did suffer from a number of endemic diseases, including yaws, a skin disease that can leave distinctive lesions on underlying bone tissues, arthritis and anemia. Wear patterns on bones and teeth indicate the effects of strenuous physical activities of the Chamorro people and other chronic health problems including dental disease. In addition, the Chamorros likely dealt with periods of famine and poor water resources. Chamorro skeletal remains also show a significant amount of traumatic injuries, such as broken bones, but that many of these injuries healed and left no visible evidence of being a detriment to overall health.

Nutrition

As the old adage says, “You are what you eat,” and sometimes, the materials we consume can leave traces in our bones. Indeed, bone analysis of Chamorro skeletal remains has been important for understanding traditional diets among the Chamorro people. It is believed that the ancient Chamorro diet consisted of a variety of plants and marine animals. These included coconut, breadfruit, taro, bananas and rice. Fruit bats and land crabs provided some protein, but most of the protein in ancient Chamorro diets was obtained from fishing.

Studies by Hanson and Butler on Chamorro remains from Saipan, Rota and Guam have revealed that the Chamorros subsisted primarily on a terrestrial plant-based diet of roots supplemented by fish in an otherwise protein-deficient diet. These marine resources from lagoons or the surrounding reefs made up about 30-35 percent of the diet of the Chamorro people. However, variations were found between Chamorros on Guam and Saipan and Chamorros on Rota who seemed to have diets consisting more of deep ocean species. This cultural adaptation has been attributed to the relative lack of reefs surrounding the island as compared to Guam and Saipan.

Analysis of a specific isotope of carbon in bone collagen, a type of protein found in bones, can also reveal food types and amounts eaten by ancient societies. Ambrose and others have proposed that, based on the prevalence of dental caries on Saipanese samples and experiments with carbon compound analysis of different food types, that Chamorros also may have consumed large amounts of seaweed or even sugar cane. Although according to Ambrose et al. there is no real archeobotanical or ethnohistoric evidence to support this large consumption in the islands of Guam and Rota, the island of Saipan seems to have shown a reliance on these items in the prehistoric diet.

Dental health

Studies of teeth of ancient Chamorros reveal interesting aspects of nutrition, diet and health as well as unique and shared cultural practices. In general, despite their diets rich in root starch and sugars, Chamorro tooth samples show little evidence of tooth decay, abcesses, pre-death tooth loss, or other dental ailments. The chewing of pugua, or betel nut, with lime (afok) seems to have contributed partly to this observation.

One of the positive effects of betel and lime chewing seems to be the reduction of dental caries, or cavities. This may be due to several factors: for example, the chewing of the rough fibers of the betel cleanses the teeth; the increased production of saliva caused by chewing also increases the proteins which help fight bacterial activity; the high pH of the slaked lime commonly chewed with pugua’ counteracts the acidity that could lead to tooth decay. The purposeful staining of teeth also seems to have had an effect of preventing the growth of cavity-causing bacteria because of the protective layer the stains placed on the tooth enamel. In contrast, children’s deciduous (or nonpermanent) teeth were more likely to show dental caries, which possibly is linked to poor diets, early weaning or by exposure to chronic diseases.

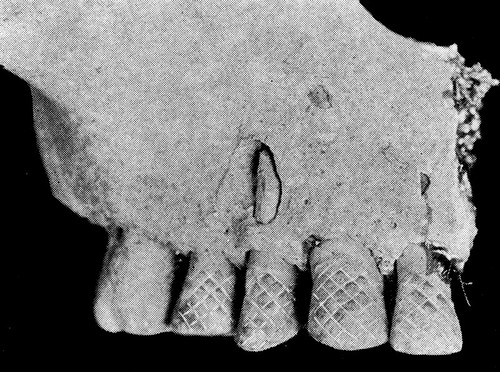

An interesting aspect of Chamorro culture was the purposeful staining of teeth, which according to Spanish accounts, was done primarily by women for cosmetic purposes. The teeth were stained with “black coloring [mixed] with gum to make it long lasting.” In addition, some individuals incised their teeth with cross-hatch patterns that may have had a decorative function, as well as indicate social status. Betel nut (or pugua’) and lime chewing also produced reddish stains on tooth enamel. In some skeletal samples from recent studies, stained enamel was not found in individuals under sixteen years of age; however, after age twenty-three, staining was found in 92 percent of the adult teeth studied. Douglas, et al., suggest the purposeful removal of incisors of both the upper and lower jaw, a practice documented in ancient Hawaiians, may also have been found in the Apurguan sample. They suggest this, too, could possibly be another type of cultural alteration of the teeth practiced by ancient Chamorros.

Physical activities

According to Hanson and Butler, prehistoric Chamorro skeletal remains show distinct wear patterns that indicate strenuous physical activities or repeated or habitual motion, in particular in the bones of the lower back, and the presence of bony outgrowths at the base of certain male skulls. The Chamorro people, as a seafaring culture with some agricultural subsistence, undoubtedly engaged in activities that required upper body strength and agility. Arriaza attributes the signs of back trauma found in more recent skeletal remains on Guam to the increased activity involved in the construction and movement of heavy latte stones, a cultural practice that emerged before the arrival of Spanish explorers and which characterizes the Latte era of Chamorro history.

The fact that both male and female samples showed evidence of back strain would seem to indicate that both sexes were involved in this community labor force. However, Pietrusewsky et al. note that such evidence of trauma to the back is not present in samples from Saipan, Tinian and Rota. Such back trauma might be attributed instead to differences in physical activity among the different islanders.

In addition, Heathcote has described the presence of localized overgrowths at three distinct muscle attachment sites on the back of the head that would indicate the great strain placed on upper body muscles in the course of activities that require heavy lifting. According to his studies, certain Chamorro males stand out among Pacific Islanders in general because of the size of these bony outgrowths. Like Arriaza, Heathcote postulates that these growths are the result of increased muscle strain due to heavy lifting, possibly from the construction of latte formations and the use of carrying poles to transport latte stones to their assigned placement sites.

Life expectancy and inter-island, inter-cultural comparisons

Pietrusewsky and others surveyed skeletal remains from the different Mariana Islands for health and disease in prehistoric Chamorro populations. Although there are biases in the representation and distribution of different age and sex groups in their samples, their studies indicate a life expectancy from birth at 26.39 to 33.71 years of age, with the life expectancy of adults at about 45 years of age. It was also observed that these Chamorro samples had relatively high fertility rates ranging from 5 to 6.5 children for women who survived to age 15 to 45. The populations sampled were also relatively tall, with a stature comparable to populations of Polynesians in pre-contact Hawai`i. Because of this the researchers conclude that Chamorros had adequate nutrition, although dental studies indicate various levels of physiological stress and disease.

Differences seen among the different Mariana Islands, such as the underdevelopment of dental enamel or evidence of anemia, could be more the result of environmental factors, such as inadequate water supply or famine caused by typhoons, or chronic diseases and parasites. These were seen more often among Chamorros in the northern islands of Saipan and Rota than Chamorro samples from Guam.

Pietrusewsky and others assert that their research lacks an adequate study of temporal changes or adaptations of Chamorros, as most of the skeletal samples are from the Latte era and very few remains exist from pre-Latte times. Their study, though, does raise interesting observations about inter-island differences among Chamorro populations of the Marianas.

For example, while it was expected that Chamorros on Rota would experience more environmentally traumatic episodes due to the frequency of storms, small island size and freshwater shortages, they found that Chamorros on Saipan seemed to have more evidence of physiological stress. Perhaps, they concluded, the Chamorros of Rota, during these periods of stress, would move to larger islands such as Guam temporarily, or the small population of Rota simply did not show as many stress indicators as the more heavily populated island of Saipan.

Additionally, based on wear of ankles, knees, shoulders and backs, it is believed that Chamorro populations on Guam experienced more stress involving labor and physical activity. However, more studies of Chamorro remains using increasingly advanced and noninvasive scientific and anthropological techniques could possibly add more to the growing body of knowledge about human adaptation of the Marianas and the Pacific.

Repatriation issues and physical anthropology on Guam

Some points to consider

Ever since the passage of repatriation legislation in the early 1990s, the treatment and disposition of culturally sensitive artifacts and especially, human remains, in repositories all over the United States have changed dramatically. The Native American Graves Repatriation Act, passed in 1990, mandated that all federally funded institutions inform native groups about the nature and extent of their Native American collections.

NAGRPA, in essence, forced museums and other institutions to inventory their collections of material culture from indigenous groups and prepare them for return to their respective sites/people of origin, or to develop treatments that are respectful and sensitive to indigenous beliefs and practices. The return of the Hornbostel collection to Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands in 2000 by the Bishop Museum exposed other challenges and the highly political and contentious issues surrounding repatriation of human remains.

For example, the situation on Guam pointed to questions of who can claim ownership and responsibility for human remains. Although indigenous Chamorros do not qualify under NAGPRA because they are not a federally recognized Native American group, the Bishop Museum, by returning the remains, set an example for other museums in the US to formulate policies dealing with repatriation for non-NAGPRA communities.

The Government of Guam set up a task force to explore the repatriation of Chamorro remains back to Guam, and in consultation with the Bishop Museum, developed a plan for their return. Chamorro activist groups also became engaged in the process and were instrumental in expediting the return of Chamorro remains through protests, lawsuits, and by partnering with Hawaiian-based activist groups, such as Hui Malama.

Local debate also centered on whether the remains should be made available for future studies, perhaps with less destructive methods, or if they should be immediately buried out of respect. For observers of the impact of NAGPRA on institutions across the United States, the issues of repatriation were embedded in a conflict of ethics, perspectives and cultural values, and the situation was similar to debates on Guam. Questions of whether scientific value and archeological inquiry outweigh historical and cultural connections to human remains were expressly argued among different facets of the Guam community. The Government of Guam looked to the CNMI for their example of dealing with repatriated or newly discovered human skeletal remains.

In the Northern Marianas, it was determined that the handling of Chamorro human remains should be done with utmost respect and that any analysis conducted to increase knowledge of Chamorro culture and history be limited with the intention that the remains eventually be reburied. As such, current Guam law states that anthropological review of human remains shall be minimal and only for a duration specified by the Historic Preservation Officer prior to reburial (GCA §76504).

The enactment of this law has placed the Government of Guam as the body responsible for Chamorro human remains, and several assemblages of bones have since been reburied or relocated at the Guam Museum. However, securing the needed funding to provide adequate storage facilities for skeletal materials prior to reburial has been an ongoing challenge for Guam, as well as regulating construction and development projects that unearth and damage ancient burial sites. While researchers may never have open access to Chamorro skeletal remains as they had with the Hornbostel collection, and some archeological and physical anthropology projects may never be completed, it is clear that a fairly substantial body of work has already been accomplished, leading to a record of publications and studies that inform the scientific community of the history and cultural heritage of Chamorros in the Mariana Islands.

For further reading

Ambrose, Stanley H., Brian M. Butler, Douglas B. Hanson, Rosalind L. Hunter-Anderson, and Harold W. Krueger. “Stable Isotopic Analysis of Human Diet in the Marianas Archipelago, Western Pacific.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 104, no. 3 (1997): 343-361.

“Ancient Remains Reinterred.” Protehi I Kuttura’ta, Newsletter of the CNMI Division of Historic Preservation, 3.2 (Aug 1999): 1-7.

Arriaza, Bernardo T. “Spondylolysis in Prehistoric Human Remains from Guam and its Possible Etiology.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 104, (1997): 393-397.

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation. An Overview of Northern Marianas Prehistory. By Rosalind L. Hunter-Anderson and Brian M. Butler. Micronesian Archaeological Survey, Report Number 31. Mangilao: MARS, 1995.

–––. Procedures for the Treatment of Human Remains in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: HPO, 1999.

Goldstein, Lynne, and Keith Kintigh. “Ethics and the Reburial Controversy.” American Antiquity 55, no. 3 (1990): 585-591.

Guam Executive Order 2000-03 of 28 January 2000, Relative to Establishing a Task Force to Recommend the Disposition of the ‘Hornbostel Collection’ of Remains of Ancient Chamorros Now Housed at the Bishop Museum in Hawaii.

Hanson, Douglas B., and Brian M. Butler. “A Biocultural Perspective on Marianas Prehistory: Recent Trends in Bioarchaeological Research.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 104, no. 3 (1997): 271-290.

Ichida, Hajime, and Yukio Dodo. “Cranial Variation in Prehistoric Human Skeletal Remains From the Marianas.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 104, no. 3 (1997): 399-410.

Leigh, Rufus W. “Dental Morphology And Pathology Of Prehistoric Guam.” Memoirs of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum 11, no. 3 (1929): 1-18.

Pietrusewsky, Michael, Michele T. Douglas, and Rona M. Ikehara-Quebral. “An Assessment of Health and Disease in the Prehistoric Inhabitants of the Mariana Islands.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 104, no. 3 (1997): 315-342.

Thompson, Laura M. Archaeology of the Mariana Islands. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin, No. 100. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1932.

University of Guam College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, Anthropology Resources & Research Center. Taotao Tagga’: Glimpses of His Life History, Recorded in His Skeleton. Gary M. Heathcote. Non-Technical Report Series Paper No 3. Mangilao: AARC, 2000.