OPI-R: Organization of People for Indigenous Rights

Although Chamorros have a long history of resisting the different colonial administrations that have governed the island, the latter decades of the 20th century are marked by the emergence of formalized indigenous activist groups. These groups mobilized to addressed the island’s ongoing colonial status.

While probably not the first activist group that comes to mind, the Guam Congress, in its own way, engaged in activism for the Chamorro people during the years under naval administration. The Guam Congress was formed as an advisory body to the US Naval Government of Guam in 1917. Its members, however, used the formalization of the Congress not only to advise the naval governor, but also to mobilize their efforts toward achieving civil government and US citizenship on Guam. In the 1960s, under civilian leadership, Guam’s political leaders took up the reins of their new government and challenged the US Congress modify the Organic Act for the right to elect their own governor of Guam and Congressional Delegate.

The indigenous activist groups that emerged in the 1970s—and continue to function in the present—however, represented the rise of new generations of Chamorro activists who were not necessarily members of the formal political leadership. The Organization of People for Indigenous Rights, or OPI-R, was one such organization. Its name made a play on the Chamorro word oppe, meaning “to answer.” In the case of OPI-R, the Chamorro word was more broadly understood to mean “to speak out.”

Background

The activist organizations that arose in the 1970s and 1980s formed in response to ongoing efforts on Guam to address the island’s status as a colony of the United States. Since the initial American occupation of the island in 1898, Chamorros had demanded a greater measure of civil, self-government and US citizenship through which they believed they could secure guaranteed civil rights. Although the Organic Act of Guam passed in 1950 seemed to address these issues by establishing a civil government and congressional US citizenship, the decades that followed made it clear that self-government and the full rights of citizenship were still lacking on Guam. Post-World War II land seizures by the US military, uncontrolled immigration, the complete oversight of the US over Guam, and other deficiencies in Guam’s ability to exercise self-government or enjoy the full rights of citizenship highlighted the imbalance between the local and federal governments. To address these issues on Guam, the government of Guam organized political status commissions to explore political status options, and also held two Constitutional Conventions (ConCon), the first to review the Organic Act and the second to draft a Guam Constitution.

The first constitutional convention was held from 1969 to 1970. The delegation reviewed the existing Organic Act of Guam and proposed amendments to it; lobbied for an elected governor and delegate to the US Congress; and prioritized increased immigration and land condemnation as primary issues of concern. A second convention was held from 1977 to 1978, and resulted in an actual draft constitution for Guam, rather than simply deliberating on amendments to the existing Organic Act. The US federal government, however, placed restrictions on the draft constitution which ultimately required that whatever Guam proposed not supersede or deviate from the existing federal-territorial relationship. Many on Guam contested these restrictions believing that they undermined the core purpose of a constitution for Guam, which was to achieve an alternate political status that would afford full self-government. In short, this ultimately led to the rejection of the draft constitution by Guam’s voters in 1979.

In the 1980s, Guam pursued a commonwealth political relationship with the US similar to that currently in place for the neighboring Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. The Draft Commonwealth Act was approved by the Guam electorate and forwarded to the US Congress where it was ultimately unsuccessful. The political status commissions and the ConCons that worked through these processes, however, were formally organized by the government of Guam to represent the interests of the island’s residents. However, activist groups also appeared to represent the interests of the indigenous Chamorro people. Since its formation in the 1980s and over the decades that Guam attempted to address the defects in its relationship with the US, the Organization of People for Indigenous Rights has remained a highly energetic, dynamic and vocal activist group that sought to advance and protect the interests of the indigenous Chamorro people.

20th century Chamorro activism

As Guam leaders tried to achieve political status change through a constitution, a new breed of Chamorro activism arose. Several organizations formed in the 1970s to address various issues of concern ranging from specific policies and practices to larger socio-political affairs. The People’s Alliance for Responsive Alternatives (PARA), for example, was formed in 1978 and led by Robert Underwood. PARA was founded initially to challenge English-only language policies at the Pacific Daily News (PDN). Members of PARA launched a successful campaign known as “PARA PDN”—a play on the Chamorro word “påra” meaning, “to stop.” The PARA PDN slogan, then, literally meant “stop PDN.” PARA’s efforts, which included speeches and a public demonstration at the PDN’s Hagåtña office, as well as a mass cancellation and symbolic burning of subscriptions, resulted in the newspaper conceding to the organization’s demands. The group went on to fight successfully for the inclusion of the Chamorro language in signs at airports in Guam and Saipan.

Although PARA’s initial agenda centered on the specific issue of language, by 1979 it soon broadened its goals to address larger issues of concern to the Chamorro people. As debate over the federally-restricted draft constitution persisted, PARA merged with another existing organization known as PADA, The People’s Alliance for Dignified Alternatives. PADA formed specifically to resist the draft constitution. Members of PARA and PADA soon realized that their overall goals aligned and so they joined forces. The result was the activist organization Para Pada Y Chamorros, literally meaning, “stop slapping Chamorros.” The group soon became known simply as PARA-PADA.

PARA-PADA contested the draft constitution primarily because of restrictions mandated by the US Congress through an Enabling Act (P.L. 94-584). According to the act, any draft constitution for Guam must remain within the existing federal-territorial relationship. The federal restriction further mandated that any draft constitution recognize US sovereignty over Guam, and that any government formed as a result of the constitution mirror the three-branch government of the US. PARA-PADA also challenged the draft constitution in its failure to allow Guam control over local immigration and the lack of any defined avenues through which Chamorros could resolve injustices created for them by the US military or Department of Interior.

Fearful that the draft constitution would derail any chance of Guam achieving an alternate political status, PARA-PADA aggressively launched grassroots education campaigns, demonstrations, and other activities toward defeating the constitution. The draft constitution ultimately was rejected in a vote held on 4 August 1979. Over 10,000 voters (just over 81 percent of voters who participated in the vote) voted against ratification of the Guam Constitution as drafted in the second Constitutional Convention. PARA-PADA is credited with playing a significant role in the draft’s defeat.

The rise of OPI-R

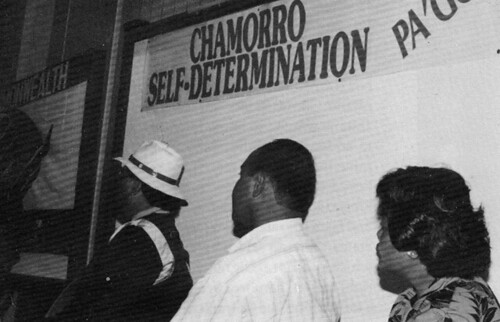

In 1981, the Organization of People for Indigenous Rights, or OPI-R, was founded. Its membership included many of the members of PARA-PADA who drew from their experience in the previous decade. While PARA-PADA and other activist organizations of the time had formed because of specific issues such as language policy, the constitution, land, and so forth, OPI-R formed with the intent of addressing a far broader and overarching long-term goal for Guam: self-determination.

Defined as a people’s right to determine their own political destiny, self-determination was first acknowledged by the international community in the United Nations Charter in 1945. The UN further asserted the inherent right to self-determination for peoples across the globe in the UN’s Declaration 1514 of 1960, also known as the “Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples.” The declaration acknowledged colonialism as an impediment to world peace and a denial of human rights. The 1966 Covenant on Civil and Political Rights also asserted the right of all people to self-determination and to choose their own political status. The passage of these documents by the UN ushered in an era of decolonization for the globe. In the region of Oceania alone, this era of decolonization led to the formation of numerous island states that asserted political independence or other political statuses of their choosing.

Guam witnessed its neighbors exercising their right to self-determination and likewise made a bid to secure that same inalienable right. The question of who was the “self” in “self-determination” quickly surfaced. OPI-R took the stance that the right of self-determination belonged specifically to the Chamorro people. OPI-R’s position caused island-wide debate in its exclusion of non-Chamorro groups who had settled on Guam for many years. The group, however, maintained the position that while such groups were due respect and dignity for their contributions to the island over many years, it was the Chamorro people of Guam who had their right to self-determination denied to them. OPI-R further maintained that it was illogical and unjust to allow outsiders to move to Guam and participate in decisions reserved for the indigenous people of the island who had a special and extensive historical relationship to the land.

Given that the Constitutional Conventions were ultimately unsuccessful, the Guam Legislature established the Commission on Self-Determination in 1980 to explore new avenues toward political status change. In 1981, the question of Chamorro self-determination was confronted head on by the Commission and became the central concern at commission meetings. OPI-R maintained a strong presence and voice during this time. Meetings were held throughout Guam’s villages during which OPI-R and other advocates for Chamorro self-determination lobbied for their cause. By 1982, the Commission on Self-Determination made a formal recommendation to the island’s elected leaders to recognize “indigenous rights to self-determination.”

Although many elected leaders supported self-determination as a right belonging exclusively to the indigenous Chamorro people of Guam, many did not aggressively advance the issue for fear of losing re-election in the 1982 gubernatorial and legislative elections. The bill to recognize self-determination as a right reserved for Chamorro people ultimately failed because of a lack of majority support in the Guam Legislature.

That same year, a plebiscite vote was held to gauge the desires of the people of Guam with regard to political status. As legislation to recognize the Chamorros as the people holding the right to self-determination was never passed, all registered voters on the island were welcome to vote on the different political status options.

OPI-R actively tried to prevent the plebiscite vote from occurring within the established guidelines. The group protested the plebiscite through numerous letters and other testimony, opposing the process and criteria established for eligibility to vote. OPI-R remained concerned that should the process continue, there would be grounds to conclude that Chamorro self-determination had been fulfilled. The group further feared that Guam would be removed from the United Nations List of Non-Self-Governing Territories, ultimately removing international recognition of its continued status as a colony with the right to decolonize. OPI-R filed motions in both the Superior Court of Guam and the US District Court in an attempt to delay the vote. These motions were denied and a plebiscite vote was held on 20 January 1982.

Voter turnout was only 37.2 percent in the January vote. This was significantly lower than the average 80 percent voter turnout in previous island elections. OPI-R held the opinion that Guam voters did not participate in the plebiscite largely due to confusion about the political status options available to them and dissatisfaction with the lack of recognition of self-determination as a right belonging exclusively to the Chamorro people. Still, a run-off election was held in September 1982 in which all of Guam’s voters could choose between the two leading choices that were selected in the January election: Statehood or Commonwealth. The September election resulted in the overwhelming support of commonwealth status as the desired political status of the voters.

OPI-R and the Draft Commonwealth Act

Following the election, the Commission on Self-Determination went on to pursue commonwealth status for Guam. A new Commission on Self-Determination was organized to prepare a draft of Guam’s commonwealth act. However, in a letter to the newly formed Commission in 1984, OPI-R reaffirmed its desires for a change in political status toward full self-government. The organization followed up its request to the Commission by continuing to observe commission meetings and offering input toward protecting Chamorro self-determination. A Draft Commonwealth Act of Guam was produced by the Commission in 1985, and OPI-R’s success in lobbying for Chamorro self-determination became evident in the preamble of the draft act. It acknowledged the Chamorro people as a political entity holding power and influence over political status. Despite the inclusion of Chamorro self-determination in the Draft Commonwealth Act, OPI-R remained concerned and vocal about the legal definition of “Chamorro” as those who obtained US citizenship by virtue of the Organic Act of Guam in 1950. This raised concerns as it included many who may have been on Guam in 1950, but who were not necessarily Chamorro. It further proved problematic in that it included individuals who were living away from Guam. OPI-R sought stronger language and a concrete definition of who Chamorros were beyond the Organic Act.

In 1987, the Draft Commonwealth Act was put on the ballot for adoption by the electorate. Article 1 relative to the US-Guam relationship and Chamorro Rights, and Article 7 relative to immigration were largely rejected due to weak or vague language related to these issues. As a result, the articles were rewritten, and in November 1987, the question as to whether to adopt the revised Draft Commonwealth Act was posed to the voters in a special election. OPI-R was aggressive in encouraging a hunggan (yes) vote in favor of the act.

The Draft Commonwealth Act was approved by voters in the November election. It was submitted to the US Congress in 1988. In 1989, the House Subcommittee on Insular and International Affairs met in Honolulu, Hawaii to discuss the act. Among many others activists, members from OPI-R attended the meeting and presented impassioned testimony not in support of the Draft Commonwealth Act, but rather in support of the rights of the indigenous people of Guam.

The act never progressed in Congress, because of the refusal of Guam’s leaders to concede to efforts by the federal government to revise or remove provisions in the act for Chamorro self-determination, mutual consent between the governments of Guam and the US, and local control over immigration.

OPI-R did not limit their work to Guam, but brought their message of decolonization for Guam and Chamorro self-determination to the global stage. Since the early 1980s, one of the key OPI-R member, Ron Rivera, requested and later gained approval to make presentations for Guam at the United Nations, together with similarly situated political jurisdictions that were working toward ending their colonial relationships with their administering countries. Rivera believed that the United Nations’ forum offered a reasonable and objective way to focus upon the Guam-United States relationship. OPI-R was the first non-governmental or non-adminstrative related group from Guam to speak to the UN. Prior to this, representatives who spoke to the UN on Guam’s behalf all supported the United States.

OPI-R stands out as a strong force in Guam’s quest for self-determination. Their efforts to protest US colonialism on Guam and their diligence in promoting and pursuing Chamorro self-determination reverberate in the present. Many members of OPI-R continue to advance such causes in their everyday lives and careers. In addition, their work provided the impetus for continued Chamorro activism which persists today. Although Chamorro people continue to struggle in the 21st century over the limitations of their relationship with the US, organizations such as OPI-R have set the stage for indigenous activism to grow and to persevere as viable and effective means of resisting ongoing colonialism on Guam.

OPI-R flyer

OPI-R flyer provided by the Micronesian Area Research Center (MARC)

Video clip: Let Freedom Ring

A clip from the film Let Freedom Ring, The Chamorro Search for Sovereignty by the Cabazon Band Of Mission Indians in 1997. This clip features a member of OPI-R presenting to the United Nations.

Let Freedom Ring, Clips 1-8 from Guampedia on Vimeo.

For further reading

Ada, Joseph, and Leland Bettis. “The Quest for Commonwealth, the Quest for Change.” Kinalamten Pulitikåt: Siñenten I Chamorro (Issues in Guam’s Political Development: The Chamorro Perspective). The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1996.

Cristobal, Hope Alvarez. “The Organization of People for Indigenous Rights: A Commitment Towards Self-Determination.” In Hinasso’: Tinige’ Put Chamorro–Insights: The Chamorro Identity. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1993.

Monnig, Laurel. “‘Proving Chamorro’: Indigenous Narratives of Race, Identity, and Decolonization in Guam.” PhD diss., University of Illinois, 2007.

Souder-Jaffery, Laura, and Robert A. Underwood, eds. Chamorro Self-Determination: Right of a People. Hagåtña and Mangilao: Chamorro Studies Association and Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1987.