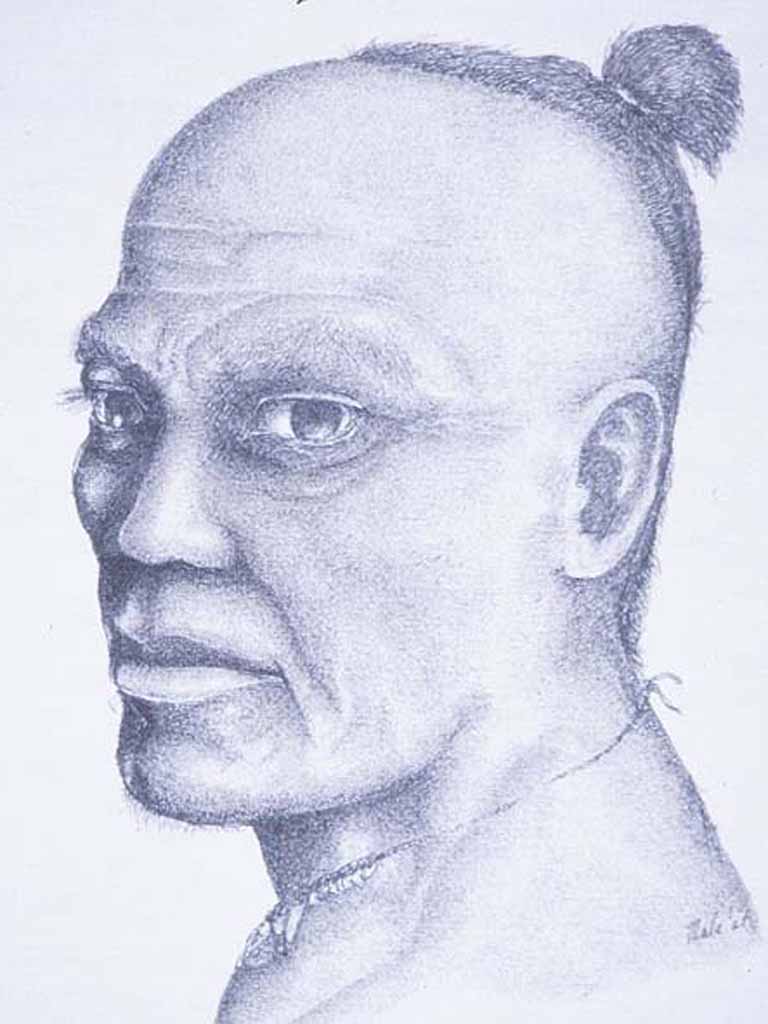

Hurao

Called CHamorus to fight

Hurao is one of the most celebrated Chamorro/CHamoru chiefs in Guam’s history. He was a Hagåtña Chamorri (high caste) in the late 1600’s, who with the backing of the village makanas (spiritual leaders), was key in instigating the Spanish-CHamoru War.

With the arrival of Spanish missionaries on Guam, the traditional power structure of the island was severely disrupted. While some high caste people adopted the teachings of the church and gained a new found prestige relative to the rest of the island, other nobles whose influence was built on the indigenous belief systems maintained their influence by opposing the foreign presence.

Hurao was one of these chiefs. Initially, he had been baptized by the Spanish, and accepted the new Christian religion, but he resented Spanish efforts to subjugate CHamorus. He became most enraged when his dear friend Chafae was arrested and killed while in the custody of Spanish troops. Chafae’s death motivated Hurao to fight back.

Following the arrival of Father Luís de San Vitores, who started the Spanish mission in the Marianas, Hurao consolidated his power by preaching an anti-colonial message that reached the receptive ears of the makanas.

Upon the return of San Vitores from a missionary trip in Tinian in June of 1670, Guam was in the midst of a shortage of food. Fruits and crops had ceased to grow due to a lack of rain. After witnessing many of the people praying to their ancestral gods to end the drought, San Vitores convinced them to pray to the Christian God. The next day, rain arrived bringing the missionaries new influence and at the same time taking it from the makanas. The makanas, however, also took credit for producing the rain and won back some of the Christian converts.

Hurao and the makanas elevated the struggle for power by spreading the word that if the CHamorus did not drive out the missionaries, the Spanish presence would bring the drought back to Guam. Minor skirmishes were nothing new, but island-wide fighting broke out following the death of two people, said to be from sickness brought on from pouring “poisoned” holy water on their heads during baptism.

A CHamoru then killed a Spaniard named Peralta, who had been collecting wood with which to make crosses. Seeking European justice, the Spaniards rounded up suspects in order to make an arrest. With no credible evidence, all the suspects were released. However, the CHamorus took great offense to this foreign custom and sought vengeance for the insult. Hurao joined Chaco, a Chinese man who was another enemy of the Spanish, in physically removing the missionaries from the villages.

With suspicions that a CHamoru was responsible for the move, the Spanish made an arrest. A group led by a leader named Gufac attempted to free the arrestee. During the ensuing fracas, Gufac was killed giving Hurao and Chaco the impetus to declare war. An impassioned speech made by Hurao rallied the troops. An estimated 2,000 CHamoru warriors took up arms after the customary exchanging of gifts and respect was performed to win over neighboring villages.

Spanish sympathizer, Antonio Ayhi, warned the Spanish of Hurao’s plans giving them time to fortify the Hagåtña church and mission.

This battle was significant in that it represents the first mass movement against the Spanish, as well as a shift in the tactics of CHamorus, which is why the wars lasted for so many years. In this battle, the Spanish noted that CHamorus seemed to no longer irrationally fear the sound of guns, and created defenses (trenches) and defensive weapons (shields) in order to protect themselves.

The Spanish seized Hurao in the early stages of the battle to make it clear that they did not fear attack by the CHamorus. Thinking the war was over, the Spanish pushed for peace. The CHamorus viewed this as a sign of weakness and the battle continued.

Guam was hit by a typhoon during this battle leaving the CHamorus weakened. But they attacked again, and again failed to win. Their only request was the release of Hurao. San Vitores, in a show of good faith, finally released the leader.

Hurao organized another attack but it, too, failed.

San Vitores was eventually killed by another chief named Matå’pang in Tomhom (Tumon) on April 2, 1672. A group of priests and Spanish soldiers met with CHamoru leaders to discuss peace after San Vitores’ death. Without provocation, a soldier shot and killed Hurao while he stood with his back turned on May 11, 1672. The Spanish-CHamoru War lasted on Guam until 1684, with the last uprising in the northern Marianas reported in 1695.

Hurao became most known for the speech he delivered, which inspired the army of 2,000 to fight the Spanish. Today he is celebrated as a hero for his intellect, and his speech is often quoted as an example of CHamoru resistance, and remains a contemporary call-to-consciousness in Guam’s continued colonial conditions.

A CHamoru language and cultural immersion program for children founded in 2004 was named after Hurao because of his “enough is enough” message, said program founder Ann Marie Arceo. As during the time of Maga’låhi Hurao, CHamorus still struggle to speak their language and practice their cultural beliefs amidst colonial rule. Hurao, Inc., like its namesake, is fighting this by teaching CHamoru children their language and cultural practices. In a very real way, the program has helped to keep Hurao and his message alive.

Hurao’s speech

The Spaniards would have done better to remain in their own country. We have no need of their help to live happily. Satisfied with what our islands furnish us, we desire nothing. The knowledge which they have given us has only increased our needs and stimulated our desires. They find it evil that we do not dress. If that were necessary, nature would have provided us with clothes. They treat us as gross people and regard us as barbarians. But do we have to believe them? Under the excuse of instructing us, they are corrupting us. They take away from us the primitive simplicity in which we live.

They dare to take away our liberty, which should be dearer to us than life itself. They try to persuade us that we will be happier, and some of us had been blinded into believing their words. But can we have such sentiments if we reflect that we have been covered with misery and illness ever since those foreigners have come to disturb our peace?

Before they arrived on the island, we did not know insects. Did we know rats, flies, mosquitoes, and all the other little animals which constantly torment us? These are the beautiful presents they have made us. And what have their floating machines brought us? Formerly, we do not have rheumatism and inflammations. If we had sickness, we had remedies for them. But they have brought us their diseases and do not teach us the remedies. Is it necessary that our desires make us want iron and other trifles which only render us unhappy?

The Spaniards reproach us because of our poverty, ignorance and lack of industry. But if we are poor, as they tell us, then what do they search for? If they didn’t have need of us, they would not expose themselves to so many perils and make such efforts to establish themselves in our midst. For what purpose do they teach us except to make us adopt their customs, to subject us to their laws, and to remove the precious liberty left to us by our ancestors? In a word, they try to make us unhappy in the hope of an ephemeral happiness which can be enjoyed only after death.

They treat our history as fable and fiction. Haven’t we the same right concerning that which they teach us as incontestable truths? They exploit our simplicity and good faith. All their skill is directed towards tricking us; all their knowledge tends only to make us unhappy. If we are ignorant and blind, as they would have us believe, it is because we have learned their evil plans too late and have allowed them to settle here.

Let us not lose courage in the presence of our misfortunes. They are only a handful. We can easily defeat them. Even though we don’t have their deadly weapons which spread destruction all over, we can overcome them by our large numbers. We are stronger than we think! We can quickly free ourselves from these foreigners! We must regain our former freedom!

Editor’s note: This speech was recorded as it was told to French Jesuit Priest Charles Le Gobien in 1700. Le Gobien was the secretary to the French Jesuit missions. He compiled and edited the writings and letters of the early Jesuit missionaries in the Mariana islands.

By Victoria-Lola Leon Guerrero, MFA and Nicholas Yamashita Quinata

For further reading

Benavente, Ed L.G. I Manmañaina-ta: I Manmaga’låhi yan I Manmå’gas; Geran Chamoru yan Españot (1668-1695). Self-published, 2007.

de Morales, Luis, and Charles Le Gobien. History of the Mariana Islands. Mangilao: University of Guam Press, 2016.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. “From Conversion to Conquest: The Early Spanish Mission in the Marianas.” The Journal of Pacific History 17, no. 3 (1982): 115-37.

Lévesque, Rodrigue. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vols. 1-13. Québec: Lévesque Publications, 1992-1998.

Risco, Alberto, SJ. The Apostle of the Marianas: The Life, Labors, and Martyrdom of Ven. Diego Luis de San Vitores, 1627-1672. Translated by Juan M.H. Ledesma, SJ and edited by Msgr. Oscar L. Calvo. Hagåtña: Diocese of Agana, 1970.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1995.