Fumatinas Titiyas yan Fuma’gasi Magagu: Places of Romance

Romantic sites in pre-war Guam

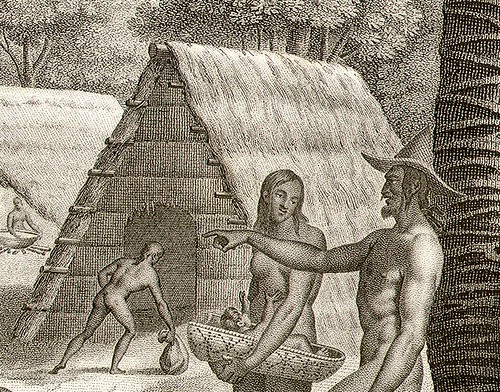

Prior the Spanish colonization of Guam, Chamorro culture was fairly liberal about issues of romance, marriage and sex, even when compared with the norms of today. With the incorporation of Catholicism into Chamorro culture, however, this changed. Men were pushed to the top of the social hierarchy displacing a more co-equal balance between sexes. Divorce was prohibited and public expressions of romance and sexuality were restricted. Much of the oppressive cultural norms came down to the regulation of interactions between unmarried young men and women to keep them from engaging in “immoral” or sexual activities until they were married or until their match had been approved by their respective families.

This meant that the activities of young men and women were, except in the cases of siblings or close relatives, highly segregated. This would change somewhat during the American colonial period, when boys and girls attended compulsory public education in the same classrooms. But for the most part, the interactions that young women and men would have with each other would either be closely watched, chaperoned, or very limited.

Place of women

In line with the patriarchal nature of Catholicism, the purity and morality of girls was much more closely guarded and protected than that of boys. Girls who engaged in romantic or sexual activity were generally much more punished than their male counterparts. Girls would often perform daily chores or activities in a large group with other female relatives and were followed and watched by one or more male relatives. Older siblings or cousins were expected to be the enforcers and defenders of their sister’s morality, and thus beat up or threaten any potential Valentinos, who came near their female relative.

Younger male siblings would often operate as chaperones, and would be expected to keha (report) on any romantic or sexual activities their sisters were participating in. It is for this reason, that it was commonly said that the best way to a girl’s heart is through mañ’elu-ña (her siblings).

Romance

“Romance” was allowed under strict supervision. Officially, young men and women could meet romantically, but only with family approval and under the watchful gaze of nearby relatives. Physical contact was unacceptable, and even words spoken would be heavily scrutinized. The romance of courting was subsequently heavily stifled.

Meeting outside of this rigid framework was possible though difficult and required parties to sneak around and keep their liaisons secret. But those moments and places in which these young people were able to meet outside of the oppressive rules of society and their families, held intense emotional and romantic power. And in their everyday youthful creativity, they found ways of transforming some of the most mundane or boring sites into places ripe with romantic or sexual meaning.

Look of love

Most feelings of love and lust at this time were silent and remained unspoken, because it was more than likely that a person had never even actually spoken to or spent real time with the object of his or her affection. The result was that some of the most intensely romantic sites were those where one was able to simply see his or her love interest, not necessarily speak to them. At i Gima’ Yu’os (churches), funerals, gupot siha (parties) and other events or locations in which large community gatherings would take place, young men and women could see each other and sometimes, if they were lucky, interact with each other. The chaos of the gatherings would often cause breakdowns in the usual rigid restrictions on movement and interaction and so young Chamorros were afforded some freedom to mingle, even if it just boiled down to a lustful or yearning gaze.

Titiyas and love

The key for Chamorros hoping to find a place to express themselves outside of society’s rigid structure was to get you and your love interest alone. Especially for women it was very difficult to simply leave the house and roam around. But there were ways that young people did accomplish this, and especially as they got older, they did it through the using of work or chores as secret sites for romantic interludes.

As children got older and especially became teenagers or young adults, there were tasks which they allowed to or required to perform on their own. Some of it was as simple as travelling from one place to another, from home to school or home to work. Other activities in which they could sometimes expect to be alone were working on the farm, taking care of younger siblings, preparing food and washing clothes. The earlier that the activity took place in the day, the better, in terms of using it for these types of meetings. Early morning meetings, hours before the sun rose, were ideal.

Setting and communicating times and dates for these meetings could naturally be difficult. A chule’ guagua or a “basket carrier” or a messenger, was often used to relay information between parties. A basket carrier was usually a neutral individual, who could be trusted to pass messages back and forth, but also be trusted to not fall in love with the love interest either!

The uncertainty of schedules made these sorts of meeting dangerous. Times and places could be arranged, but there were no guarantees that either party would be alone at the arranged time. It is for this reason that many couples came up with signals in order to communicate whether the times was right for a rendezvous.

Paths or trails could be marked in order to communicate whether or not the time was right. Certain songs could be chosen, and sung to warn off an approaching lover. Sometimes the volume or intensity of an activity could be the message. Women who were not alone could grind the corn on the mitåti, or wash clothes by the riverside very loudly to warn off their suitors.

Postwar Guam

Following World War II, this aspect of Chamorro culture changed slowly as the lifestyle of Chamorros shifted drastically. Changes in Guam’s physical landscape, increased desire to be more American, the island’s transition from a subsistence agricultural economy to a wage economy, and the increased institutionalization of mandatory public schooling, all led to a loosening of close knit relations that families required for survival prior to the war. As families drifted and moved apart, as more and more young Chamorros gained the means to provide for themselves and live independently, the chances for romance and meeting potential love interests became much much easier and required far less sneaking around.

This isn’t to say that overnight the rules for romantic interaction suddenly disappeared. During the 1950s and 1960s on Guam it was still common to have young people’s interactions tightly controlled and have families approve of marriages or relationships. But as more time has passed, romantic interactions have become far less policed or controlled, and thus the symbolism associated with them not contained to specific or secret sites as they were prior to the war.

By Michael Lujan Bevacqua, PhD

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Flores, Judy, ed. Kustumbren Chamoru: Chamorro Life Before and After World War II, A collection of oral histories by students of History of Guam classes, Fall 2004. University of Guam: Mangilao, GU, 2004.

Guam Council on the Arts and Humanities Agency. “Chamorro Courtship and Marriage Practices in the Early 1900’s.” A collection of stories from the Chamorro Courtship and Marriage Conference, Maite, Guam, November 1989.

Hemplon Nåna Siha: A Collection of Chamorro Legends and Stories. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Department of Chamorro Affairs Research, Publication, and Training Division, 2001.

Iyechad, Lilli Perez. An Historical Perspective of Helping Practices Associated with Birth, Marriage and Death Among Chamorros in Guam. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2001.

Nelson, Beth. “The Look of Love.” Latte: The Essence of Guam, (February 1997): 36-43.

Russell, Scott. Tiempon I Manmofo’na: Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1998.

Souder-Jaffery, Laura Marie Torres. Daughters of the Island: Contemporary Women Organizers of Guam. MARC Monograph Series 1. Mangilao: Micronesian Areas Research Center, University of Guam, 1987.