Warfare

View more images for the Warfare entry here.

Ancient CHamoru warfare

Early European accounts of ancient Chamorro/CHamoru warriors marveled at their strength, skill and fearsome weapons. According to one missionary, CHamorus were amongst the strongest of any race yet discovered, exemplified by an incident where a CHamoru lifted up two Spaniards, one in each hand.

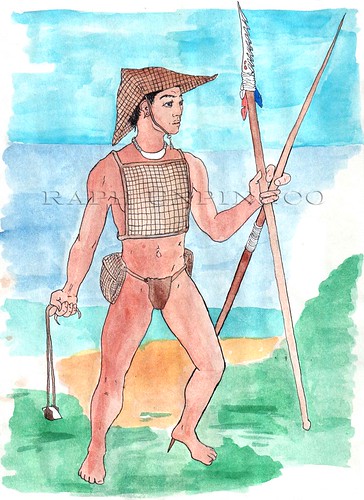

Ancient CHamorus wielded three types of weapons, acho’ atupat (sling and slingstone), spears and clubs. Slingstones were egg-shaped projectiles made from either hardened or burnt clay or stone which were hurled using an atupat (sling) woven from akgak (pandanus) or coconut fiber.

Spears were wooden with their ends either sharpened and fire hardened or equipped with a tip made of human bone. These spears could be used for long-range attacks or close combat. The spears with human point tips were particularly deadly. A leg bone was taken from a deceased person and carved into a sharp point with two rows of teeth. The shape of the tip allowed it to easily penetrate the flesh, but the teeth made it impossible to extract without tearing the flesh, thus even minor wounds from it could cause terrible infections. According Spanish military leader and Governor Jose de Quiroga in 1680, these spears, “the worst weapons in the whole world, because there is nothing that can be done against their poison.”

Ancient CHamorus also made clubs and machete-like weapons called damang and katana for close quarters combat. In addition to offensive weapons they also wove defensive items such as helmets and gnuga guafak (breastplates) and supply items like hagug (a tall basket) made with akgak for carrying food and provisions to battle.

Ancient CHamoru warriors regularly competed in games to practice and prove their skills in wielding weapons and hand to hand combat. In one game, according to an account by Fray Juan Pobre in 1602, opponents would throw spears at each other, catching them in mid-air and then mocking he who threw it by saying things like “do you think I’m blind?”

Warriors were called to battle using a kulo’ (shell horn) and often carried woven babao (banners). Prior to fighting they would seek the help of manganiti (ancestral spirits) in securing victory by appealing to the makåna (practitioners of magic and herbal medicine). In some battles, the skulls of ancestors were placed on the battlefield in order to ensure victory.

Wars between ancient CHamorus were primarily battles between villages over matters of honor. Insulting another village or village maga’låhi (highest ranking male), infringing on another’s fishing rights, as well as feuds between husband and wife could lead to a war between clans or villages. War in this context however was not about conquering or destroying your opponent, but about proving your superiority and raising your clan’s or village’s prestige.

Thus strategy and gaining a clear advantage of your opponent was more important then vanquishing their forces, so instead of outright battle, homes and gardens would be burned, traps would be set and armies would seek to ambush their enemies. If physical conflict did ensue, whichever side suffered two or three casualties or even injuries would surrender and seek peace over the conflict by offering ålas (turtle shell) or other precious shells to the victor.

By Michael Lujan Bevacqua, PhD

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

I Ma Gobetna-na Guam: Governing Guam Before and After the Wars. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1994.

I Manfåyi: Who’s Who in Chamorro History. Vol. 1. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education and Coordinating Commission, 1995.

Russell, Scott. Tiempon I Manmofo’na: Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1998.

Topping, Donald M., Pedro M. Ogo, and Bernardita C. Dungca. Chamorro-English Dictionary. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1975.