Filmmaking

Telling Guam’s stories

Though it is still relatively small, filmmaking is growing on Guam as both an art form and an industry. On an island that values story-telling, community, and preserving history and traditions, film is a natural fit as an arts medium and technology is only expected to help it continue to flourish.

The seeds of filming images of Guam began to take root in the US Naval Era of Guam. There is footage of US Navy Captain Richard Leary and his family riding on a horse-drawn carriage in front of the Governor’s Palace. Although this early footage may not be considered a film, it was the first time that the technology to capture moving images came to Guam. In a sense, it may be considered the first attempt to tell a story through film on Guam. The Baptist Church also filmed scenes on Guam in the 1930s in order to raise funds in the United States to build churches on the island.

Post World War II

Filmmaking became more important on Guam in the aftermath of World War II, as the military and others attempted to document the military presence in the island and tell the stories of the island’s re-growth to stateside audiences.

In addition to news footage, the wartime saw the production of military films such as Marines at Tarawa-Return to Guam, an official US Marine Corps picture that won the 1944 Academy Award for best short-form documentary. The two-reel film, alternately titled With the Marines at Tarawa, followed the marines as they took control of the islands of Tarawa (part of the Republic of Kiribati) and Guam, after Japanese occupation during the war. The film was shot by combat photographers in the field, and is noted for being one of the most graphic portrayals of wartime casualties of its time.

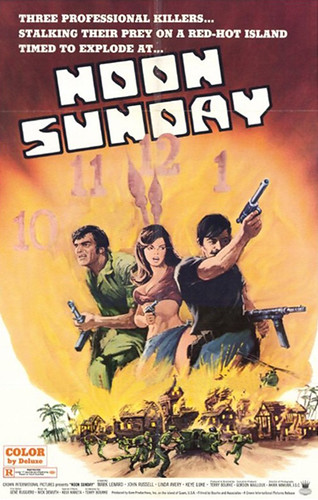

One of the island’s first involvements in a commercial film was in the 1971 feature Noon Sunday, directed by Terry Bourke and produced by Bourke and local resident Gordon Mailloux. Portions of the film, an action feature following two mercenaries on a “South Sea” island as noted in promotional materials, were filmed on Guam with others filmed in the Philippines. The film starred Mark Lenard, John Russell, Linda Avery and Keye Luke.

The 1967 Japanese monster movie Son of Godzilla (Kaijûtô no kessen: Gojira no musuko) also shot much of its footage on Guam to take advantage of low costs and beautiful scenery. Apart from Godzilla, most of Guam’s films would draw from the war for material for the next few decades.

On the 50th anniversary of Guam’s liberation in 1994, Guam’s Liberation: The Story of Guam’s People in the Years Surrounding WWII, produced by local resident Annette Donner, was released. The picture documents the prewar experience, Japanese invasion, occupation and the island’s liberation through interviews and archival footage.

Seventeen years earlier, Yokoi and His Twenty-Eight Years of Secret Life on Guam (Yokoi shoichi: Guamu-to 28 nen no nazo o ou), was released, a Japanese documentary by Nagisa Oshima about the Japanese soldier Shōichi Yokoi who hid out in a Talo’fo’fo cave for twenty-eight years following the end of the war.

Feature films

One of the first feature productions shot by local filmmakers was Guam: Paradise Island, which was shot on video and presented on television in 1984. Produced and directed by Herman Crisostomo and written by Jillette Leon-Guerrero, the feature used local actors, models and music to portray some of the island’s history and its stories.

Other local filmmakers, including Carlos Barretto, Tony Sanchez, Kathy Coulehan, Vince Diaz, Jillette Leon-Guerrero, Carmen Kasperbaurer, Rita Nauta and Baltazar Aguon have produced projects on island documenting its unique history and culture such as History of Guam Through Song and I Tinituhan: Puntan yan Fu’una.

Kathy Coulehan made significant contributions to documenting Chamorro stories. Her work, done in the 1990s, is still aired today. In some cases, it is the only video document on the subject. Carlos Barretto continues to produce video profiling Guam’s notable businessmen/women and the contributions these men/women made to Guam, noting the significant events that led to the creation and/or development of Guam’s commercial/business industry.

Pacific Islanders in Communication

Seeking to develop the talents of Pacific Islander filmmakers, the Honolulu-based non-profit organization Pacific Islanders in Communications (PIC) was formed in 1991 with two Chamorros, Catherine Cruz and Carol Ibanez, as founding members. The group seeks to support and encourage the development of PBS quality media in Hawai`i, Guam and other Pacific Islands, and has held numerous producer’s academies and workshops on Guam to build the island’s filmmaking industry.

PIC aims to seek out these stories and filmmakers and provides funding and distribution of the finished projects. PIC is one of five minority consortiums established by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting created to give Pacific Islanders greater opportunities to have their films and stories aired for national audiences via PBS. Some of the films about Guam that PIC has financed are Sacred Vessels, Chamorro Dreams, The Insular Empire: America in the Mariana Islands, and Tano y Chamorro (a working title).

Still, as Chamorros make their mark on the filmmaking scene, the island government has faltered in its attempts to become involved in filmmaking. In 2003, Hollywood director Albert Pyun contacted the Guam Economic Development Administration about shooting the action flick Max Havoc: Curse of the Dragon on the island. Seeking the publicity and exposure that a large-scale feature would give to Guam, the government put up $800,000 to guarantee a bank loan on which Max Havoc’s makers later defaulted. The Los Angeles Times describes the straight-to-video release that resulted from the controversy in the June 13, 2007 article “Camera, legal action.”

In the resulting ninety minutes of cinematic chop sockey, Swiss-born Mickey Hardt stars as a champion kickboxer-turned-sports-photographer drawn into a web of intrigue on Guam. The plot revolves around women in bikinis, clashes with Japanese assassins, a coveted jade dragon filled with cremated remains and a sinister “grand master” played by David Carradine. Carmen Electra has a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo as a beach vendor.

Cultural connection

Local filmmaking began to thrive in the 1980s and 1990s, as Guam filmmakers began to take advantage of film’s ability and people’s interest to document the island’s wide range of histories and traditions. Beyond just telling the stories of the island, these films attempted to explore how the stories contributed to making the island and its people what they are today.

The sentiments during this time were based upon the island’s push for political status and therefore, documenting the hardships and suffering of the Chamorro people endured during World War II was an important part of the political status argument. The Chamorro people were not US citizens and had very limited political rights at the time.

As a result, Guam saw more and more of its history re-created in film, and it was only a matter of time before filmmakers capitalized on that interest by producing more films about Guam, the culture, the stories, and history.

One of the first films to tackle the local identity was Chamoru Dreams, by Eric Tydingco in 1996. The short film, fully shot on Guam, follows the filmmaker as he interviews locals and explores the island to discover what it means to be Chamorro in the modern day. Pacific Islanders in Communications produced the film as part of the Pacific Diaries series.

Another film was Pattera: Midwives of Guam, a video documentary by Karen A. Fury Cruz in 2001. This film documented the personal stories of trained Chamorro midwives in the beginning of the 20th century, and traced how their lives reflected the island’s shifting culture of the time.

Like Chamoru Dreams, Pattera and many others, contemporary local films have tapped into the island’s rich oral traditions. For centuries Guam’s stories and other information were passed on by word of mouth, and filmmaking is a natural extension of that tradition. Local writer and producer Baltazar Aguon, who has worked on several local films, explained that in the past, stories were just told. In film, filmmakers can create a scene and show what people are doing, thinking and feeling. Viewers can almost live in that period. Because this is a new medium for Guam many more stories are expected on film.

The expansion of film also has the potential to democratize education and the flow of information. In the island’s past, many traditional skills – such as making crafts and tools, dancing, singing and other arts – were only able to be learned on a one-to-one basis and then only by a select few. They were lost to those who were not able to experience and learn them in person. Once these skills are documented on film, they become accessible, conceivably, to anyone who chooses to pursue them.

Aguon points to a local film in the works documenting Project Proa, a local initiative to build and launch Chamorro Proa canoes using traditional materials and techniques. By documenting this process it makes these traditions accessible to anyone who watches the film.

Future of film on Guam

As technology becomes more accessible, so does filmmaking, and many see this contributing to a blossoming of filmmaking as an arts medium on Guam.

While filmmaking got its start on Guam with emphasis on documentaries, it has since moved into the commercial world. Distinctions are now apparent between the styles of films produced on Guam and the people involved in each of those styles of filmmaking. With more filmmakers given the opportunity to work on projects that fit a certain genre and style, there are choices now for filmmakers to crew or produce.

In the early 1980s and 1990s, the scarcity of projects meant few crew to call upon and those that were called, did so because that was probably the only project available to work. The lack of work translated to a film industry virtually non-existent.

Today however, it’s a different story. With choices of projects to work on and various genres of films being produced, the industry is slowing developing. While still not enough to leave a day job, there are a growing number of filmmakers making a living doing film work.

With the advent of digital mediums, the growing number of graphic artists together with the ever-improving talents of those in the film, the explosion of there art come together on television in the commercial world.

Guam television stations, KUAM, Sorenson Pacific and MCV, to name a few, are always seeking local programming. Independent producers such as Therese Arroyo-Matanane, Nathan Denight, Marissa Borja, and Brian and Peter Duenas are developing shows and providing them for broadcast. They are not affiliated with a broadcast station but provide local programming to them.

A search for “Guam” or “Chamorro” on the video-sharing web site Youtube.com results in thousands of videos, from news clips and family movies to short films complete with soundtracks. With putting out a film now within reach to anyone with a computer and digital camera, Guam is making its mark in filmmaking like never before. The availability of technology is allowing local filmmakers to experiment with new techniques, styles and methods of distribution.

In 2005 a Los Angeles filmmaker with Chamorro roots, Alex Munoz, made a film with Baltazar Aguon, Therese Arroyo-Matanane and Bert Sardoma, Jr. called “Måtto Sainata as Hurao: The Return of the Elder Hurao,” a short vignette about the ancient Chamorro leader who called islanders to unite against the Spanish invasion. The film, distributed on the Internet, is entirely in the Chamorro language with English subtitles. Munoz is currently working on a longer feature film.

In 2008, Chamorro filmmakers and brothers Kel and Don Muna completed production on Shiro’s Head – The Legend, a feature-length film they wrote and directed and which was shot entirely on Guam using local actors. Shiro’s Head was shown on Guam in October 2008.

The Muna brothers took the additional step of documenting their progress on video, and posting those videos on the Internet for another glimpse of filmmaking on Guam.

Videos

For further reading

Crisostomo, Herman, dir. Guam: Paradise Island. Guam: Herman Crisostomo Productions, 1984. VHS.

Cruz, Karen A. Fury, dir. Pattera: Midwives of Guam. Guam: Guam Humanities Council. Pattera Video Project, 2001. VHS.

Donner, Annette, dir. Guam’s Liberation: The Story of Guam’s People in the Years Surrounding WWII. Guam: Donner Video Productions, 1994. VHS.

Feldman, Jerome, and Donald H. Rubinstein. The Art of Micronesia: The University of Hawaii Art Gallery. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Department of Art and Partners, 1986.

IMDb. “Son of Godzilla (1967).”

–––. “Noon Sunday (1970).”

–––. “Dokyumento: Jinsei no gekijô” Yokoi Shôichi: Guamu-tô 28 nen no nazo o ou (TV Episode 1977).”

Kihleng, Kimberlee S., and Nancy P. Pacheco, eds. Art and Culture of Micronesian Women. Mangilao: Isla Center for the Arts and Women & Gender Studies Program, University of Guam, 2000.

Pacific Islanders in Communications. “Home.” 11 February 2023.