Matrimony and Social Change in the Marianas during Spanish Times

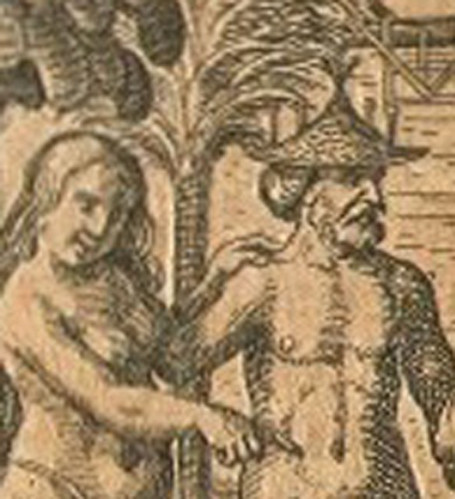

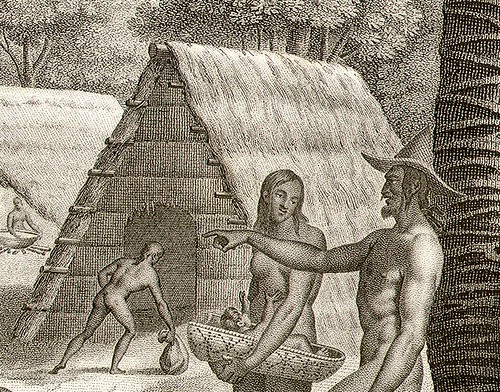

Ancient Chamorros/CHamorus customarily chose their own spouses, rather than their families dictating who they would choose for a partner. The bride and groom’s families, however, had to approve of the choice. The groom provided gifts ranging from food items to services and even land, to the bride’s family to gain their acceptance.

Traditionally, there was a time of trial or testing before the marriage where the family could see the groom’s ability to labor or his level of skill. If the suitor was a farmer, his prospective in-laws investigated his fields and crops. If he were a fisherman he was required to demonstrate his skills in the presence of his intended bride, as well as his ability to sail a proa (canoe). If he proved suitable, then plans for the marriage would go forward.

Each family clan also had a male as its head though Chamorro women made most of the decisions regarding the family. Chamorro husbands were responsible for providing for their wives, who were held in high esteem in the Mariana Islands during ancient times. In 1680 Padre Francisco Garcia observed:

In each family the head is the father or elder relative, but with limited influence. A son as he grows up neither fears nor respects his father. The father has one advantage: he gives out the food.

The father’s role in the family unit was as a provider of food. Each family clan also had a male as its head though Chamorro women made most of the decisions regarding the family. Garcia observed:

In the home it is the mother who rules, and the husband does not dare give an order contrary to her wishes or punish the children, because if the woman feels offended, she will either beat the husband or leave him. Then, if the wife leaves the house, all the children follow her, knowing no other father than the next husband their mother may take.

Christianity introduced slowly

During the early years of the Spanish colonization period, Jesuit missionaries launched an intense, and eventually successful campaign of conversion to Christianity. The conversion campaign, however, was neither peaceful nor inexpensive, lasting for more than 20 years.

At first the Catholic priests introduced the sacrament of baptism. Through this sacrament Christian names were given to Chamorros followed by their own name, such as Antonio Ayhi, Diego de Aguarin and so on.

Next, schools for boys and girls were established in an area of Hagåtña called San Ignacio de Agadña, and also in the northern village of Ritidian. By the year 1673, (in the midst of the Spanish-Chamorro wars) it was reported by Jesuit priest Francisco Gayoso that some Chamorro women were taught the principles of chastity and they became fond of the Holy Mary. Subsequently the sacrament of marriage was introduced.

On 10 June 1676 five religious men of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), 14 soldiers and two families arrived on the ship San Antonio de Padua. The newly arrived missionaries were distributed among the villages of Hagåtña, Ritidian, Tarague, Orote (Sumai) and Pago [Agadña, Ritidyan, Tarrague, Orote, Pago]. All of them were occupied in the work of baptism and marriages. This group, according to Garcia, served as an example for Chamorros “in the education of children and they were useful for the skills that they employed for the good of all.”

A short time later a group of Christian weddings took place between Marianas (converted Chamorro women who had been educated in the girls school) and Spaniards as well as some Marianos (converted native men).

In December 1680, Fr. Antonio Jaramillo, SJ reported to the Council of Indies about the progress of the missionary work in the Marianas:

With Doctrine and education, people relocated to towns and because of the new settlement they were more accessible. Those that were married in accordance to their custom and about 150 couples married in the church come to the church on Sundays, where about 1,000 natives congregated and were all indoctrinated. Those married in the church attended confession and received communion. Unmarried Chamorro women rejected their former life and became proud Christians.

Regarding the interracial marriage of the Chamorro women, Fr. Jaramillo, reported that:

A large number of Filipino and Spanish soldiers married Chamorro girls that show chaste Christian behavior disregarding the inequality between Spanish men and native women. They lived with them in holy matrimony, believing that by virtue of this sacrament infidel women are sanctified because they were married to faithful and Christian husbands. They were living in peace and exercising Christian behavior. God may bless them with fecundity and many children and setting a good example for their children and for others.

These married women are living in the Garrison [Agadña], where they have one priest assigned to them to conduct their Christian education, explaining to them the obligations of the married life, how they must raise their children and how to behave toward their husbands, learning some trades that would be useful to themselves, such as sewing and other similar things from which some of these women profited.

In their former life, when these women were living with their parents in the house, they were used to observing that the authority figure of the household was the woman, she was in command and the husband obeyed, but now the roles of husband and wife have been inverted. The husbands are the head of the household and they [the women] have accepted the civilian obligations of marriage.

In the year 1693, an early Church Census reported the number of married native couples in Guam (spelled as Guahan in the report):

| Locality | Married Couples | Married: Consort Absent |

|---|---|---|

| Agadña, Fr. Gerardo Bovens, SJ | 72 (2) = 144 | 104 |

| Santa Rosa de Agat, Fr. Lorenzo Bustillo, SJ | 55 (2) = 110 | 9 |

| San Antonio de Fina, Fr. Felipe María Muscati, SJ | 55 (2) = 110 | 0 |

| San Dionisio de Umatag, Fr. Juan Felipe, SJ | 78 (2) = 156 | 11 |

| Malesso‘ Church of San Dimas, Fr. Antonio Cundari, SJ | 63 (2) = 126 | 0 |

| Nuestra Señora de la Concepción of Pago, Fr. Matias Cuculino, SJ | 37 (2) =74 | 0 |

Young Chamorro women, Garcia reported, followed the example of their friends who married in the church, rejecting the old tradition in which their parents or clan leaders arranged a price for them with the uritaos (bachelors). The act of deciding whom to marry was conditioned to the approval of their families, since traditions were deeply rooted and they considered the consent of their parents to be essential for the wedding to happen.

Marriage traditions eventually blended

Marriage traditions have evolved, blending old and new. What used to be the “price” paid by the uritaos, in the Spanish colonial society, became the aog (presents to the girl during the engagement), typically a complete bridal outfit for the bride, a large part of the cost of food, drinks and music for the fandango and the services in the church, as reported by anthropologist Laura Thompson in 1936.

As for the Chamorro women who became subject to the laws and obligations of matrimony, marriage in the church may have given them a certain prestige and status into the new colonial social order. In the Marianas, like other colonies in the Spanish empire, once the people accepted the monarch of Spain, the Laws of the Indies regulated all civil affairs as well as marriage as sacrament, including civil matters regarding the family.

Married women from the garrison in Hagåtña were taught new trades, such as sewing skills, which produced changes in the economic and social structure in the island. The offspring of Chamorro women and Spanish or Filipino men eventually became the elite in the Marianas, since they were educated in the schools established by the Jesuits and had access to wealth and power.

While the Spanish legal system made men the leaders of society, Chamorro women however, whatever their status, continued to be the keepers and transmitters of the culture and traditions to the children, a practice which continues until this day.

For further reading

Archivo General de Indias, AGI, Ultramar, Legajo 562, Doc. No. 18, Cuaderno 153 and 154.

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

García, Francisco. The Life and Martyrdom of Diego Luis de San Vitores, S.J. Translated by Margaret M. Higgins, Felicia Plaza, and Juan M.H. Ledesma. Edited by James A. McDonough. MARC Monograph Series 3. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 2004.

Gayoso, Francisco, SJ, Relación de las Empresas y Sucesos Espirituales y Temporales de las Islas Marianas 1668-1672. Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, Roma, Philipinas 13, Legajo 141- 207.

Repetti, William C., SJ. “An Early Church Census of Guam.” Guam Recorder, n.s., 1 (2 & 3, 1972): 69.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.